WHATEVER YOU'D LIKE SUSAN SONTAG TO THINK, SHE DOESN’T

"The only interesting answers," she says, "are those which destroy the questions."

By James Toback/Esquire/July 1968

“Norman Mailer was there. And to back him up there was Arthur Schlesinger, the redoubtable Galbraith, Walter Lippmann, Drew Pearson, Norman Podhoretz—only Susan Sontag was missing.”

—William F. Buckley Jr. on the Capote Ball

The Dirty Little Secret was out; Norman Podhoretz, chronicler of the American intellectual scene, had told us that what writers and critics really craved was success, money and fame. Just as the Victorians had harbored a profound but hidden longing for sex, so contemporary intellectuals, despite professions of purity, were ultimately motivated by a need to be known and celebrated. The most prominent young woman in the literary world of which Podhoretz speaks, the “Dark Lady of American Letters,” is Susan Sontag, brilliant, articulate, beautiful and productive. And yet from what one had heard, Miss Sontag sought to stifle, rather than encourage, the virtually unlimited publicity and promotion available to her.

“She just killed an article in The New York Times,” said Roger Straus Jr., her publisher. “She refused to meet their reporter. I can’t say any more. Susan doesn’t want her life exploited, and I don’t blame her.”

“Susan hates interviews,” a girl friend said. “She’s not interested in becoming a household word.”

“A few years ago,” a well-known art critic noted, “you used to see her around all the time—at Andy’s, at Panna Grady’s, at the Dorn. But now she’s in hibernation.”

The impression of scrupulously guarded solitude was fortified when the voice that answered her phone—a woman’s, but deep and husky—hesitated and seemed to shift tone artificially.

“No, this is not Susan Sontag. I don’t know when she’ll be home. Try tomorrow.”

The suspicion lingered that the voice was, indeed, Miss Sontag’s, until the next day when a different voice answered, also deep but with edge and pace. It was the voice of a woman who was not friendly to pressure.

“I just killed an interview in The Times,” she said. “I refused to meet their reporter. Almost every day someone calls—for an interview, an article, or a television appearance, and I always say no. I can’t understand why anyone should care whether I eat fried eggs or waffles for breakfast. And what difference does it make that I used to go to the movies every day? All that matters is my work. Everything that’s really important about me is there.”

But what if what one wished to talk about were her work? What if the conversation were to center on Foucault rather than food?

“Okay. All right. You’re in the end zone.” Her voice was warm for the first time. “In the past I’ve only done this when a new book was released. Then it’s almost an obligation—to my publisher and to the book. But all right.”

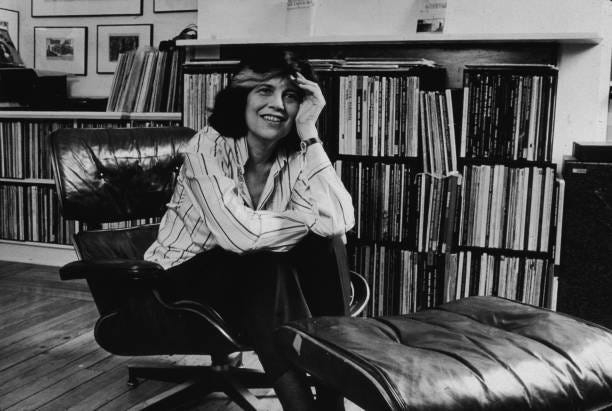

Susan Sontag lives in the penthouse of a large, dark, prewar apartment building on Riverside Drive in New York City. A uniformed elevator man asks if I’m expected, eyes me askance, and finally decides to take me up. Susan opens the door, smiles, and then returns to the kitchen where she is finishing lunch. If her reputed predilection for the bizarre and the flamboyant were valid at all, it certainly did not show in the arrangement of her home. Except for books, records and some photographs (of Garbo, Dylan, and W.C. Fields), the walls of both living room and hall are white and bare. The floors are of deep-brown wood, uncovered, and the scarcity of furniture yields an impression of empty spaciousness. Despite a generous view of the Hudson River, its spirit is redolent of monasteries.

She is dressed cheerfully and casually, in a yellow corduroy jacket worn over a red turtleneck shirt, with high brown boots hugging black woolen pants. Her black hair is thick and shoulder length, combed across from left to right, the hairline low, accentuating a heavy, almost masculine brow. Her mouth is full and her smile broad and quick. But it is her eyes to which attention returns— soft brown and resolutely steady as they penetrate your own. She introduces her son David, fifteen, beardless, gaunt, with long black hair and wide dark eyes, almost pretty. He offers his hand and then follows his mother into the living room, stretching out on the floor as she leans back in a black leather chair, stroking her hair.

“It’s not that I meant to sound cold on the phone,” she says, “but I’m just so tired of being misquoted. I think most of the people who talk and write about me haven’t read a word I’ve written. A reviewer spends half an hour glancing at a book of essays before doing his article, and then his version is accepted as though I had said it myself. The most obvious example is the essay on Camp which many people seem to think is all I’ve done. But it’s only one of about forty essays, and even by itself it’s been misrepresented. People are always using terms like ’high camp’ and ‘low camp’ in reference to it, and in fact I never mentioned either one. I don’t even know what they mean. I guess I shouldn’t complain. The audience I’m really concerned about is small—my close friends and other writers I respect. I don’t even read most of the stuff that’s written about me.”

Then the holy trinity of Success, Money and Fame was not her guarded aim?

“No, no. Not at all!” She shakes her head in disbelief. “I can’t even imagine caring about them. I’m interested in becoming a better writer, maybe a great one, and that’s all. As long as I have solitude and a place to work, and as long as I’m published and have enough money for books and movies and the opera, I’m perfectly content.”

The opera! Was this Susan Sontag, the subtle and the severe, Susan Sontag whose favorite writer was Samuel Beckett and whose most admired philosopher was Ludwig Wittgenstein?

“That’s another misconception. Why should a taste for one kind of art exclude appreciation of another? I love Strauss and Wagner. Have you seen the Met’s Die Walküre? It’s fantastic! The Beatles and the Supremes make me happy, physical . . . sexual. They’re like a pep pill. Mahler nourishes . . . my spirit, my soul.”

The spirit? The soul? The words come as a shock. In all her work there is a stubborn resistance to the grandiose and vague terminology of psychology.

“Sanity is a cozy lie,” she had written in Against Interpretation, the collection of essays that thrust her in 1961 from the highly selective world of Partisan Review into the mass-cultural realm of Life, Vogue and Mademoiselle. Morality, personality—reality itself—were viewed as tenuous and perpetually fluctuating approximations. Consciousness was a river with countless estuaries, any one of which could become the mainstream at any time. In Death Kit, her most recent novel, neither reader nor author ever knows whether the protagonist, Diddy, is dead or alive. His mind functions—through thought, fantasy and dream—but whether he is experiencing death in life or life in death is never made clear.

“I don’t know what Diddy is or even that he is,” she says, reclining into an almost supine position. “I guess he’s many things, and he learns about them through his fantasies. He’s brutal and bitchy —but he’s a poor slob, too. But the fact that Diddy’s sense of identity is in doubt doesn’t mean that mine is. Of course I change all the time—my home, my tastes, my friends. But I am very aware of being someone—in particular, a writer—and I certainly don’t think I’m insane.”

If she was not like Diddy, perhaps she was like Hippolyte, the hero of The Benefactor, her first novel. Here, after all, was a brilliant and rootless young man whose whole life was an attempt to expose himself to new experiences and so open himself—as Miss Sontag advocates in Against Interpretation—to modification of consciousness and extension of sensibility. Hippolyte’s life is an imitation and realization of his dreams, and since dreams are amoral, so are his actions. The day after dreaming about murdering his wife, for example, he blows up her house. Miss Sontag’s insistent opposition to looking for meaning or ethical lessons in any art form and her emphasis on style and formal surface seemed to indicate that her own view was also amoral.

“Oh no, of course not!” Again she is aghast. “I’m nothing like Hippolyte; at least I certainly hope I’m not. He fascinates me, but I dislike him intensely. He’s purposeless and wasteful and evil.”

Then morality, although excess baggage in art, had a place in life?

“It certainly does for me. I’d even say that the health and future of this sick, wounded country of ours is a totally moral question. It annoys me to read, as I did the other day in Dissent, about liberals who praise Stokely Carmichael for his ‘charisma’ and condemn Rap Brown for his ‘vulgarity.’ Even if that were true—which it isn’t—what difference would it make? The important thing is what they’re telling us about the way black people suffer and feel. As for Johnson, he’s brought America to the edge of insanity and yet you still hear the philistines talking about his lack of ‘style’!”

She shrugs her shoulders, shaking her head despairingly, and one can hardly doubt her sincerity or her concern. But, still, what of statements in the essays like: “Morality is only a form of acting. . . . I have arrived at a dedicated sense of agnosticism about reality. . . . Society is a game which there is no one right way to play.” Is it possible that when—in connection with promoting the avant-garde novel—she writes of the occasional necessity for “all sorts of seductive and partly fraudulent rhetoric,” that she is describing a form of discourse in which she herself indulges? She smiles, her eyes suddenly sparkling, and responds by asking if I like milk and sugar in my coffee. (“The only interesting answers are those which destroy the questions,” says Hippolyte.)

We go into the kitchen again, David following. One had heard many stories about him, how he went everywhere with his mother, even to dinner parties, how at the age of eleven he dressed foppishly, looking like a prepubescent Aubrey Beardsley, and how at thirteen he slipped into conversations on Reichian analysis and the philosophy of history with the self-assurance of a Harvard graduate student. He is the son of Susan and her former husband, Philip Rieff, a professor of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. During their marriage, which lasted from 1950 (when she was seventeen) to 1957, they both taught at Harvard, where Susan was doing doctoral work in philosophy. They collaborated on one book, Freud: the Mind of the Moralist, a brilliant and gracefully written study of the influence of Freud on modern culture, but the divorce took place before publication and it was agreed that Rieff should receive sole credit for authorship. (When asked to verify or deny the question of collaboration, Rieff’s reply is, “No comment.”) The book is dedicated to David.

“I think I’ll go for a walk,” David says. Today, in jeans and an Army fatigue jacket, he is dressed more like Bob Dylan than Beardsley.

“Do you need anything?” Susan asks.

“I could use some money—for the weekend.”

She gives him five dollars and he promises to be home soon. He shakes my hand and all of a sudden he looks just like his mother, his eyes and his smile warm and serious, his expression honest to the point of vulnerability.

Returning to the living room, Miss Sontag lights a cigarette and starts in again on politics.

“I’m really beginning to lose hope for America. It’s not Western civilization that’s crazy, it’s this country. Insanity is not just a psychological phenomenon. It’s cultural, social and historical. And there’s something about America—I don’t know exactly what—that’s absolutely mad in a way that no other place on earth is. It’s become almost a physical thing with me. As soon as I get to London or Paris, the knots in my stomach unravel. There’s a directness and warmth in people’s faces that have all but gone from here. It used to be that however frustrated I felt at a particular moment, I knew America was my home. But now a day doesn’t go by that I don’t think of moving. And it’s not like the idea of expatriation that characterized the Twenties. That was a reaction against cultural philistinism. I feel more like the people who left—or wanted to leave—Nazi Germany in the Thirties. The internal situation in America today may be better than it was in Germany then, but I don’t see any difference at all in foreign policy. I try to tell myself that the S.N.C.C. people—whom I admire so much—are just as much ‘America’ as Johnson, Rostow and Rusk. But let’s face it, they’re a small minority. And every week fifty or sixty people are leaving for Canada, good people, who come from that minority. I guess what keeps me here is a sense of responsibility. I have no illusions about my power, but even if I affect only a handful of people, I feel obliged to stay here and speak. I can’t hope to have the kind of influence that Norman Mailer and Paul Goodman have because I can’t imagine writing personally the way they do. I’m just not temperamentally capable of using the kind of direct, immediate, first-person experience that Mailer uses in his essays, but that’s precisely what makes him so effective. And yet I still feel I can do something. You know I’ve often thought that Death Kit could have been called Why Are We in Vietnam? because it gets into the kind of senseless brutality and self-destructiveness that is ruining America.”

Vietnam, she feels, is the essential issue, quoting Bertrand Russell’s assertion that the war is the “acid test for this generation of Western intellectuals.” Our conduct there is the most undeniable illustration of the fact that “the quality of American life is an insult to the possibilities of human growth.” America is still ruled by the concept of Manifest Destiny, and now, by rearing our ugly head all over the world—especially in Southeast Asia—we are literally poisoning the world.

“American use of napalm is not only a concrete and tangible evil but also a metaphor for the lethal infection we are inflicting upon the rest of humanity. It’s a big, lonely, cruel, immoral, rotting country.”

She sighs and looks out at the sun setting softly in the haze over the river and her face takes on a soft, almost reverential quality.

“Isn’t it beautiful?’ she says, and then sits silently for several moments before resuming, her voice now quieter, almost subdued. “What keeps me going is my work. Art. I’ve had enough of criticism. Another book of essays is coming out in the fall, but my real concern now is with writing novels. Art is autonomous—something pure and wonderful that need have no relation to anything or anyone by itself. Writing a novel is like giving birth to a child; once it’s out I’m relieved to be rid of it but glad that I’ve given forth something that has its own life. Then I feel a new growth inside me and the process starts again. It’s the only way I can think—or want to think—of my life.”

Suddenly she sits up straight and her voice takes back its edge.

“My heroes are Beckett and Kafka. Aside from the vast importance of their radical innovations in technique, they lived ideal lives: quiet, reserved and contemplative. They didn’t try to be movie stars; they wanted to write. In fact I don’t see why anyone would look for promotion and publicity, a large public image. I know quite a few movie stars and most of them are confused and unhappy. Having a true private vision of yourself and seeing it daily exaggerated, twisted and inverted in the mass media creates circumstances in which schizophrenia is almost inescapable. How can you constantly read about yourself, hear about yourself and see yourself, knowing that it’s not you, and keep sane? And I’m no romantic. I don’t look at insanity as poetic, tragic, fascinating or beautiful. It’s pain and imprisonment, and that’s all.”

The panic of insanity can, of course, be catalyzed by any number of agents, not only mass publicity. And for young people, Susan explains, drugs are the most potent danger. Again one is struck by the contradiction of expectation. As a champion of youth, radicalism, experimentation and consciousness modification, she would be, one had guessed, an apologist, if not a positive proponent for the mild narcotics in common circulation (marijuana, Benzedrine, amphetamine) and perhaps even for the mind-blowers (LSD, STP, mescaline). But she is wary.

“The impulse to explore the new, to open oneself to everything, is fine in itself, but, at least for me, keeping as sharp as possible intellectually is the essential thing. In particular, I’m concerned with verbal communication and the better I can write and speak, the more powerful I feel. I think drugs may heighten one sense, but only at the expense of others. You think you’ve found answers to questions you really don’t understand and won battles you’ve never fought! I don’t even like to drink; it puts me to sleep. But there are more serious consequences, especially to acid. Fifteen-year-old kids, totally unprepared for what’s about to happen, go on trips that can waste years of their life. I had a good friend in Paris, a writer of about twenty, who went through a series of hallucinations—mostly unpleasant—on the first day of an acid trip. He went to bed expecting to wake up the next morning and start work. But instead he found he was still high, too high to do anything but wander aimlessly in the street or pace around his room. He couldn’t concentrate; he could hardly communicate. His mind was in fragments. He became more and more frightened as the days went by and he kept waking up high—disjointed, nervous, and disoriented. He tried coming down with Librium and Thorazine, but nothing happened. Work was inconceivable. In effect, his mind had been temporarily destroyed. Finally, he had to go through a long-term series of chemical antidotes with a doctor before he regained the ability to think.”

Susan’s expression and voice have been oddly detached, as though she had been speaking of a passing acquaintance rather than a “good friend.” Then, abruptly, she leans forward, looks at me urgently and, arms extended, palms up, speaks emphatically.

“So why do it? I mean, okay, once in a while a joint isn’t going to hurt anyone. But it’s not for me. I want to be wide-awake and lucid, not to deaden myself into stupor or agitate myself into frenzy.”

The mention of Timothy Leary turns her expression instantly into disapproval and her voice is filled with scorn.

“He’s unspeakably vulgar. Even when drugs are a mistake, the error is lessened if the intention is serious. But the kind of blatant exploitation and intellectual sham that Leary represents and promotes can only be destructive.”

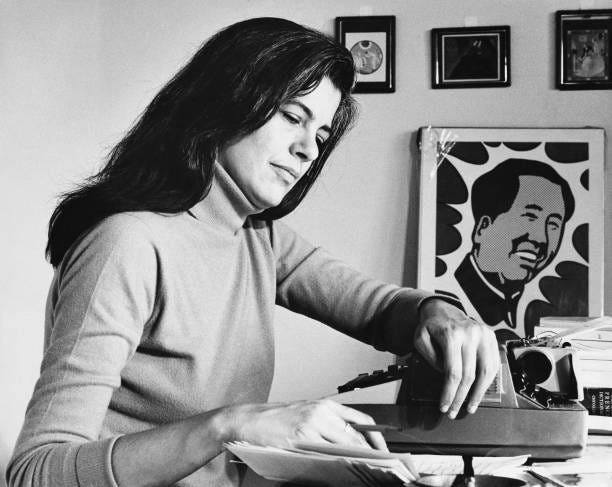

The phone rings and Susan walks across the room. It is “Eva.” She explains that she cannot speak now. A journalist is with her and she is busy. She will call back later. Coming back to her chair she eyes her typewriter, with paper rolled in, almost apologetically.

“I wish I could tell you something sensational,” she says, smiling, “that I spend my nights at orgies, for example. But, actually, although I wouldn’t necessarily mind seeing what an orgy was like, I’ve never been to one. I just don’t have time. There’s too much work to do.”

Is one being put on? Is the reiteration of privacy and anonymity, the claims to a simplicity as monastic as the decor of her home, the opposition to drugs, the praise of selfless work, somewhat too insistent for credibility? The suspicion flashes for the third or fourth time; but it never lasts. After two hours with Susan Sontag there is little with which one would not trust her. If she is far from confessional, it is hard to discern a dishonest touch in her face or a false note in her voice. One recalls the circumstances from which she sprang: Jewish parents from New York, movement West, schooling in suburban Hollywood, graduation from the University of Chicago, graduate work at Harvard, and teaching positions at Columbia and C.C.N.Y. Earlier she had spoken of “middle-class people like me.” If she was too complex to characterize solely in terms of philistine respectability and if saying that she was essentially a nice Jewish girl were as falsely banal as calling Norman Mailer a nice Jewish boy, it still seemed that the element of Susan Sontag’s image that spoke of amorality and recklessness, of hedonism and experimentation, would have to be modified. In the Notes on “Camp” she writes that “the two pioneering forces of the modern sensibility are Jewish moral seriousness and homosexual aestheticism and irony.” If her work shows a predilection for the latter, her personality has been shaped by the former.

“She’s so straight,” says a girl who studied philosophy under Susan at Harvard. “I mean you’d think from the ‘camp’ piece, her sensual look, and her radical politics that she was into everything; but actually, more than anything else, she’s . . . a scholar.”

One thinks of Emily Brontë, whose work is informed by passion and spiritual rebellion, but whose life was spent, almost fanatically, in pursuit of solitude and study in the bleak English moorlands of Haworth rectory. The silence and reserve that characterize her letters complete a picture that bears striking resemblance to Susan’s present style of life and view of herself. The difference is in public image. In the nineteenth century, with a relative paucity of communications media, only the careful self-promotion of a Byron or the eager flamboyance of a George Sand could project a writer beyond the restricted confines of the artistic community into the dimensions of a myth. Today, when Norman Mailer throws a punch or when James Baldwin speaks of the white man’s doom or when Robert Lowell refuses an invitation to the White House, it is national news. Its accessibility notwithstanding, Susan Sontag does not wish to become a legend.

“A legend is like a tail,” she says, “it follows you around mercilessly—awkward, useless, essentially unrelated to the self.”

And yet if popular misconceptions surround her—exaggerations, distortions, and half-truths—Susan was still more fortunate than many whose private lives had become public concern. Her friends are lavish in their praise of her brilliance, her warmth, and her sincerity. Even those who might have reason to resent her are either silent or qualifiedly critical. Typical of this latter group is Samuel Adams Green, director of The Philadelphia Institute for Contemporary Art, who wrote the introduction to the first comprehensive book on Pop Art. Reviewing it in Book Week, Susan was scornfully harsh, particularly with Green, criticizing his fulsome “self-congratulation.” Shortly after the piece appeared, they were introduced at a party. Green—attractive, buoyant and in his middle twenties—describes the meeting:

“She looked at me, horrified, and said she was terribly sorry, that she thought I was some stodgy seventy-five-year-old academic art critic, and that had she only known she never would have attacked me. And I saw that she meant it. She was really quite charming. We got on very well the rest of the evening, and a few weeks later she came to a party at my house.”

“I know the bitchiest, most gossipy people in New York,” says a friend of Andy Warhol’s, “but you’ll never hear them say a nasty word about Susan.”

The little hostility that does exist seems to come from two sources. First, there is the predictable male resentment against the power, influence, and success of a woman whose lethal weapon is an essentially “masculine” intelligence. A prominent editor and literary critic has been heard to remark on more than one occasion: “The trouble with Susan Sontag is that her crotch has gone to her head.” (“A novel is a novel,” says Susan. “I can’t think of anything less important in determining its value than the gender of its author.”) The second group is constituted by members of the very class of literary intellectuals to which she belongs and whose favor alone she is courting, a twist of irony illustrating once again the truism that no prophet is a hero in his own home. Denis Donoghue, reviewing Death Kit in The New York Review of Books, America’s High Church of literary journals, calls her style “unnatural,” her thought “hectic,” and adds: “She writes as if she had to do everything for herself and all at once and be God as well.”

And John Simon, conceivably the most brilliant—and indubitably the most acrid—critic working today, responds with unflinching acerbity to the mention of Susan’s name:

“We used to appear on panels, symposia, and television together, and, as she is very bright, I enjoyed our association. Then, when her ‘camp’ essay appeared, I took issue with it in a letter to Partisan Review. She answered my letter somewhat angrily in the magazine, but I still didn’t suspect that our social relationship had been abrogated—or even altered —since she had often said that polemical attacks on a writer’s work should never be taken personally by the writer. I soon began hearing, however, that she was bitching behind my back, and the next time I greeted her at a party, she turned her head away and ignored me. When I reminded her of the statement on polemical attack and personal friendship, she walked away. Shortly afterward, I learned that she had vowed never to appear with me again in public. It’s really too bad, because I should like to resume a sort of dialogue with her. But she has no sense of humor whatever, none at all.”

“I can’t imagine what you’ll write about me,” Susan says. “I think I’ll make an exception this time and read it.”

The phone rings again. She crosses the room slowly. In the pale yellow light her face looks shallow and tired.

“No, I’m sorry. I can’t; not tonight. I have to work. I’ll call you.”

I meet her halfway and we move into the hall where we shake hands and then I go out, closing the door behind me. The wait for the elevator is long and inside I can hear the determined and relentless rhythm of the typewriter. Susan Sontag’s Dirty Little Secret was that she wanted to be left alone.