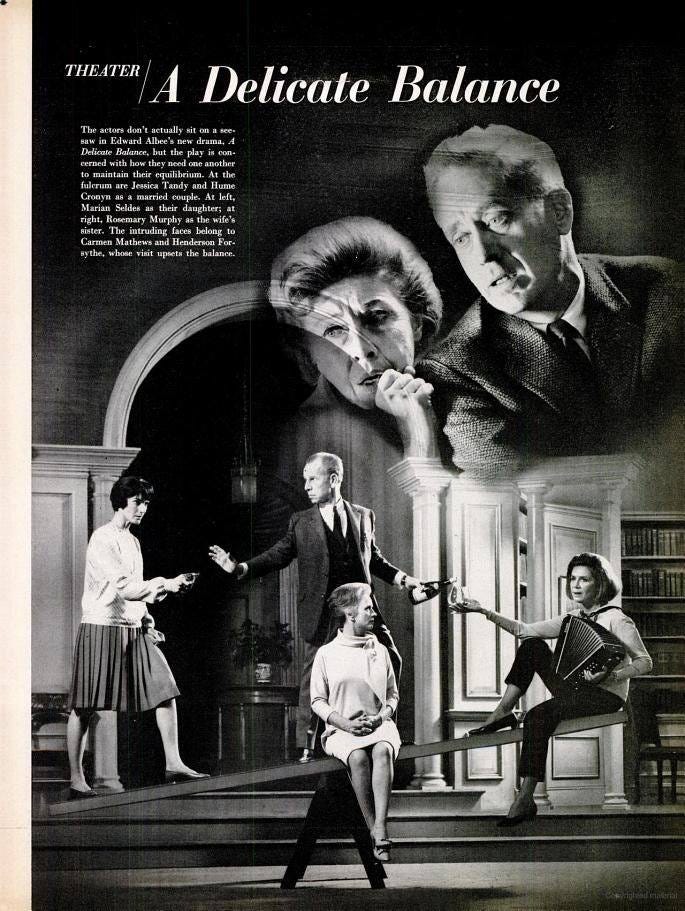

On September 22, 1966, Edward Albee's A DELICATE BALANCE opened at Broadway's Martin Beck Theatre. Directed by Alan Schneider, the play starred Hume Cronyn, Jessica Tandy, Rosemary Murphy, Marian Seldes, Henderson Forsyth, and Carmen Mathews.

Walter Kerr of The New York Times opened his review with the following paragraph: "T.S. Eliot once said, 'I will show you fear in a handful of dust,' and then he did it. In 'A Delicate Balance.' Edward Albee talks about it and talks about it and talks about it, sometimes wittily, sometimes ruefully, sometimes truthfully. But showing might have done better."

Marian Seldes told me that Albee read that first paragraph and threw the newspaper across the room. Seldes read to the end, and saw this appraisal: "Alan Schneider has staged it with infinite composure and considerable grace. William Ritman's setting is surely altogether right, and Marian Seldes, as the raven-haired Cassandra who is prone to hysterics, works hard at the passion of her utter distress. But it is an underground distress, and Miss Seldes suffers most from having to flash so much anger over unseen, unknown wounds."

Seldes told me that she didn't throw the newspaper anywhere, but she put it down with a sense of dread. "I might have disappointed a critic," she said, "but I refused to believe that the play disappointed anyone."

Word spread that Elizabeth Hardwick, a brilliant writer with The New York Review of Books, was going to write a piece attacking the power of the Times and Walter Kerr, whom she found loathsome. Hardwick's piece, appearing one month after the play's opening, reads in part: "The power of the Times is intolerable and this would be true if Walter Kerr were George Bernard Shaw, which he is not. Kerr’s taste, in the past, has been special: His impatience with experimental art is radical, his forbearance in the case of light comedies and genre pieces, such as The Subject Was Roses, is excessive. The theater will have to find some way to make the public aware of opinions other than those held by the daily press. Certain possibilities suggest themselves as a way to relieve the bondage to reviewers; the bondage is also one of the time. (Many things are gone, or crippled and abashed, before even the weekly press can offer a judgment.) During the previews, which seem to be universal now, showing among other things that apparently people will go to plays until they are told not to do so, the authors could invite the presence and solicit the opinions of those persons whose word might be relevant in forming the public taste. These short statements could be printed on opening day, in the advertisements, just as a publisher prints opinion on the back of books. Blurbs, of course, are not criticism and tend drastically toward the positive, the negative lying buried in dots. Still, they tell us something more important than most of the reviews the public relies upon: They tell us the level of the intentions of the work, give testimony to those to whom the dramatist has hopefully addressed himself. We might then have some idea, however imperfect, of the general nature of the work offered without consulting the reviewers alone on the day after opening night. Meanwhile, a threatening innovation, a “technological advance,” has already grown up around us. Television announcers are moonlighting as “drama critics.” The possibilities here outdistance one’s powers to prophesy."

So far, so good, but then came what Albee called the "elegant shiv."

"EDWARD ALBEE’S A Delicate Balance is a dull play; that is indeed the most interesting thing about it. One spends the evening thinking with surprise of all the things it is not. No, it is not spare and sharp like The Zoo Story; it is not brassy and voluble like Virginia Woolf: it is not chic and mysterious like Tiny Alice. No, it is not like any other Albee, but it echoes every one except the author himself. Listening, I thought of T. S. Eliot, Noël Coward, S. N. Behrman, and George Kelly. It is very old-fashioned, fixing itself in one of those carefully nurtured suburban houses with ferns and velvet sofas, a more or less timeless Scarsdale that reminded me poignantly of Ina Claire and “fatal weaknesses” and “deep Mrs. Sykeses,” and then suddenly a bit of suburbanized Eliot, which was less poignant, and simply rhetorical. A good deal of the dialogue has a fleshless vehemence; it is not rooted in the particular, but moves toward the general and becomes at last just so much unmotivated heavy breathing. The structure of the play is repetitive and amateurish. There is only one important bit of stage business and that is the mixing of drinks; action and dialogue return to this both “later that evening,” and “early the next morning.” But more tedious and static is the habit of the characters for assembling the family—“Well, here we all are”—and producing like a vaudeville act revelations of feeling."

And then the death blow: "Jessica Tandy and Hume Cronyn are resolutely competent performers, not greatly favored with those rich charms that usually lead young persons to seek a career on the stage. In the banal and unsteady edifice of the play, there are merely two posts that maintain but do not decorate."

A DELICATE BALANCE was a tough sell, even though other critics, generally from periodicals, whose reviews appeared weeks after a play's opening, were positive. The play limped along for 132 performances, but the play won Albee his first Pulitzer Prize, which he refused. (In a twist, Albee “accepted” the Pulitzer in order to “refuse” it, claiming that one could best criticize the prize in accepting it. He took some heat.) Both Alan Schneider and Marian Seldes believed the refusal had to do with the trustees of Columbia University vetoing the choice of the Pulitzer judges in 1963, when they voted to award the Prize to WHO'S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF? Albee said, "Who cares? I got more mileage out of refusing it than accepting." Albee did accept his second and third Pulitzers, for SEASCAPE (1975) and THREE TALL WOMEN (1994).

A DELICATE BALANCE earned five Tony Award nominations: Best Play, Best Director, Best Actress (Rosemary Murphy), Best Actor (Hume Cronyn), and Best Featured Actress (Marian Seldes). Only Seldes won, giving a terse speech claiming that she had the award because Edward Albee had written this play. Alan Schneider never forgave her for slighting him in her speech, even though they were both on the Juilliard faculty together. "He wasn't nice to me," Seldes told me, "but he was brutal to Jessie and Carmen Mathews and Rosemary Murphy." When Schneider died after being hit by a motorcycle on a London street, Rosemary Murphy took credit for the hit, and invited people out for drinks.

"Look," Seldes told me, "the play survives. It is a lovely play, and this is now acknowledged. I always believed in it." A 1996 revival was highly praised, and the play is regularly performed.

"Oh," Albee said to me once, "what does anyone know, really?"