(I wish you all a Happy Mother’s Day)

Tenn also wanted to please his mother; to impress her. “I began to think of gifts I could give to my mother,” he told me. “I knew that my mother saved things—odd things—that helped her to remember what she was and what she could have been.” The home of Edwina Williams had held paper and linen napkins on which had been written sentiments and phone numbers and poems; rose petals had been pressed into books; bottles of perfume—often never used—lined tables and shelves, and they were perpetually dusted and touched and fussed over. Each had a story and each had a place in her home until she died.

“Totems,” Tenn told me. “I wanted to give to my mother something she could place on a shelf and love, something as fragile and as transparent as those perfume bottles. Something as beloved and fraught with meaning as those rose petals and those napkins.”

…

“Let me tell you my memory of St. Louis,” Tenn said to me after many cocktails. “I think of a jar of snakes wrapped in lace and scented with vanilla. I despised my father, and every cruel act imagined in my plays emanates from his necrotic soul. I hated my mother for blandly accepting the mediocrity that was our life, and until I jumped on her train of outward-bound dreams, I hated her for moving out of the real world, where I felt she might have offered me some aid. I came to realize that my mother could only function in this world of illusions, could only survive if she could believe that one, that any, of these illusions might one day manifest itself. The writing of [The Glass] Menagerie taught me something very important about myself and about others. I believe, as I told you, that we lie in order to live, and in time, our lives become the lie. Is it benign and beneficial, or is it corrosive, bearing a cost none can bear?”

“My mother found her happiness in her past,” Tenn continued, “and it was one we all might covet—a past in which she was pretty and cosseted and appeared to hold promise. Perhaps that was her gift, her one niggardly ornament in life: a beginning in life that held promise. And suddenly the promise is gone, and reality has taken residence in her heart and head, and it is too much.” So Tenn’s mother retreated to sticky summer dances at Moon Lake, furtive kisses from men overwhelmed by her face in the moonlight, gardenia corsages rotting in the icebox, their lives as brief and fragile as the infatuations that warranted them. “And she drug us all with her to those places”—Tenn laughed—”and I knew her conquests as other boys might know baseball scores or the itinerary of Lindbergh. I could not know then, because I hated her, that my mother was allowing me into her heart, was giving me all she felt worthwhile about herself, wanted both to elevate herself in my eyes, in everyone’s eyes, but also because she needed me to see her as she saw herself. She wanted to be loved.

“There’s an old Southern saying, common among Negroes, in which they talk of their mothers after they’ve passed away. If you hear a song you associate with your mother; if you smell a scent that was distinctly hers; if you overhear a voice that reminds you of hers—you experience a pain deep with you, at your very core. They call it Mama Bones, and I felt it for the first time sitting in those theatres, watching those movies, and thinking ‘I must tell Mama how outrageous Miriam Hopkins is’ or ‘Bette Davis has totally incorporated the druggist’s wife’s mannerisms,’ and I would feel the pain, and suddenly realize that the person with whom I wished to share these reactions, these observations, was someone I believed I hated. The person I thought I hated, and felt I didn’t understand, had made me someone who could appreciate these images, these illusions, and who had probably made me a writer.”

…

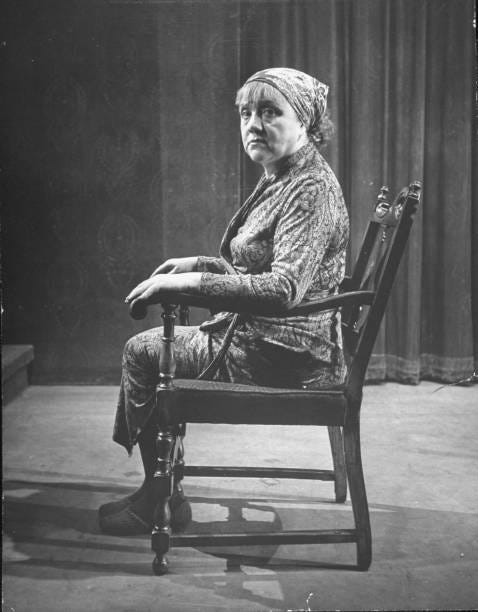

“After all the talk and all the analysis, what ultimately matters is whether or not you reach the hearts of the audience,” Tenn said, “and this Laurette [Taylor] taught me. That love that I spoke of—that is so important to the crafting of a play—extends in its production and must be carried through every performance. With Amanda I was purging myself of the hatred I had felt toward my mother and was left only with the very strong love I knew was there. So I loved her through the play. The strong, strange love—that for my sister, Rose—I poured into Laura, whose love for her brother is what truly hobbled her. I even found I could love Tom—myself—by showing him in constant turmoil in that lacy imprisonment. A prison is a prison. And the Gentleman Caller is religion and its God, the newspaper page that holds the horoscope and the society page. The Gentleman Caller tells us that we can be here right now, but the there, the glistening over there is possible and imminent and near. It’s one novena, one afternoon reverie, one cocktail…away.

“And so,” Tenn continued, “what I learned from Laurette Taylor, from my mother, from Menagerie is that we—writers, people—only conquer when we love, because when we love, we see clearly what is in front of us, and what was in our past, and what we own So love your characters, and by doing so you may ultimately come to love yourself. Laurette told me she loved my mother for me while playing Amanda, and also expressed her love for her own mother through the performance. There was a lot of love in that play, and if an audience can’t identify with these sad outcasts of Dixie, they can identify with those loves that destroyed them and those loves that liberated them.”