Shelley Winters was a friend to both Marian Seldes and to Garson Kanin.

Winters would tell me—and anyone—that Garson Kanin had “found” her, “rescued” her, “elevated” her. Winters was, she believed, floundering under her contract with Universal, being given parts that would not serve her well. Winters was considered, she claimed, a “utility” player, someone who could be a good girl, a strumpet, an old maid, a virago, a bit player. Winters was not happy with the parts.

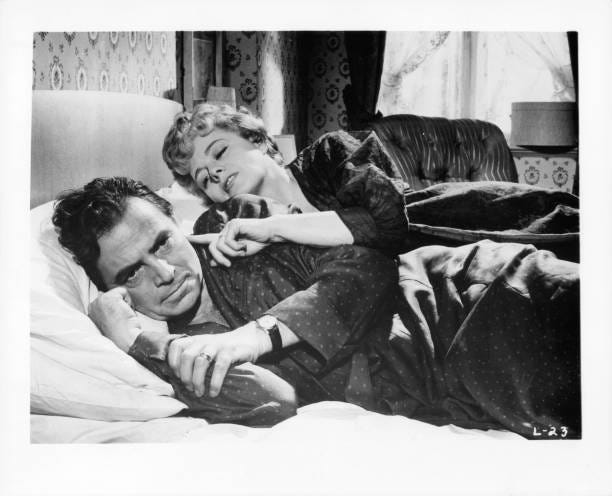

Garson Kanin and his wife and writing partner Ruth Gordon wanted Shelley Winters for a part in A Double Life, which they had written in the hopes that Laurence Olivier would play an actor haunted by the role of Othello. George Cukor was set to direct. Even though Winters would claim for decades that she was nominated for an Oscar for A Double Life, she was not. However, it was her first important role, and she claimed it changed her life. Later, Kanin would approve Winters to play Billie Dawn in a touring production of his play “Born Yesterday.”

On June 24, 1993, The Museum of Modern Art Department of Film hosted a tribute entitled “Family Values: The Kanins and the Movies,” featuring Michael and Fay Kanin, and Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin. “Together and Alone” was the subtitle. Among the speakers were Robert Osborne, Bud Cort, Ring Lardner, Jr., Mary Tyler Moore, and Shelley Winters. At the conclusion of the evening, Marian Seldes introduced me to Winters and said, “You two should talk.” Winters asked, loudly, “Why?” I liked her instantly.

We did talk, once at the Central Park South apartment where Marian and Garson lived, and later at a restaurant, and then by phone. During my time with Winters at the Kanin apartment, I asked if it were true that she had appeared with Johnny Carson asking the members of the Motion Picture Academy to vote for her, as if she were a political candidate, telling them that they had seen what she could do, and they should reward her with a vote.

“I did!” she replied, “but not quite like that. Well, yes, like that. It was for Next Stop, Greenwich Village (a film by Paul Mazursky that had opened very early in 1976). “I was good in that. I should have been nominated. The actresses nominated that year were in cameos; small parts. My part was good and it was big, and the film had not been successful. I was afraid it was forgotten, so I went on with Johnny, and I said, basically, ‘Look, we just had a Presidential election, and everyone said, ‘Vote for me, vote for me,’ and I don’t see why I can’t do the same. I didn’t know why all actors couldn’t do the same. We work hard on a film, we wait, it comes out, and we wait to see what might happen. So why not remind people of what you did?”

Did you say that a winner could “ride” an Oscar for about five years?

“Yeah,” she said. “It’s about five years. If you work hard and fast. A lot of light is thrown on you, and people want to work with you. The money and the parts get better, and then things fade, but you get a good five years. After I won for [The Diary of] Anne Frank, I did a lot of good things.”

“What were they?” asked Marian. “Wasn’t that around the time we did a play?”

“I don’t remember,” Winters said. “I think that play was earlier. Before that Oscar. But I did The Young Savages, Lolita, The Chapman Report, Wives and Lovers. I did a TV thing and got an Emmy. And then I went into A Patch of Blue, and won again, and another string of good parts came along. You get a good stretch of work. I wanted another stretch like that.

“I don’t understand why actors are criticized for promoting their work,” Winters continued. “There’s a lot of work out there. You have to stand out. You have to stand up for yourself, and remind people what you did. I don’t see the problem. It didn’t work for me for the Mazursky film, but Paul thought it was great. More people saw the film, talked about it. You know, a studio will pay to send you out to promote their film. They pay for everything. You eat and drink and talk to everyone. But if you say anything to a reporter or a writer that appears to be asking for promotion, asking for a vote, they clamp down on you and say it’s tasteless. Why? Aren’t we both selling the film? They’re selling the film, and I’m selling myself.

“Now,” she continued, “everybody does it. They take out ads; they host parties. Who knows what else they do. But I think I was one of the first, long before the Carson show. Liz Smith tells me I was walking up to people to vote for me way back in the Sixties. Maybe I was. I’m glad I did. I think I was unafraid to say, ‘Hey, I’m good. Throw me a vote.”