Rex Reed on Kay Thompson

“Once upon a time there was this amazing woman who could do anything, and once you saw her do it, it was too late to analyze what it was she did because she had already changed your life forever.”

Kay Thompson, one of the most uniquely fascinating women in New York, passed away on July 2. Roy Rogers got more space, but Kay Thompson got more tears. None of the obituaries got it right and The New York Times didn’t even try. Yes, she was best known as the creator of Eloise, the precocious 6-year-old who poured Perrier down the mail chute at the Plaza Hotel in the first of four children’s books that have sold more than a million copies, and the blazing star, with Fred Astaire and Audrey Hepburn, of the classic 1957 movie musical Funny Face . But she was so much more than that.

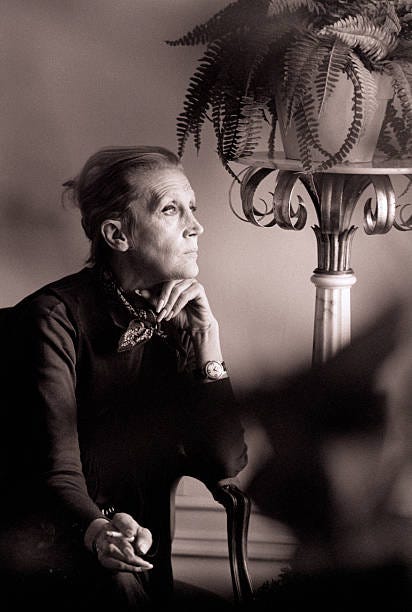

Stylish, elegant, supersophisticated and fun to experience, Kay was an accomplished singer, dancer, actress, composer, pianist, arranger, author, satirist and businesswoman who was ahead of her time for nine decades–awesomely professional and never dull. She would have been 96 on Nov. 9, but she was younger than anyone I know. She was hooked on life. There will never be anyone else like her. She invented the word “Bazazz” and she had plenty of it. She gave me the last formal interview she ever granted, and we were friends and fellow mischief-makers for 26 years. I first met her on a windy autumn day in 1972 when I interviewed her for Harper’s Bazaar .

“Bobbledy Boo Bop do Boo Bop do Bobbledy Bop!” she scatted, popping her fingers as she time-stepped her way to a corner table in the Oak Room of the stuffy old Plaza Hotel like a magic ray from a voodoo moon. She wore chamois pants by Halston with a black-ribbed Italian scoop-neck sweater, a black belt with a big silver Pilgrim buckle, no makeup, and sunglasses on her head as she folded her frame (5 feet 5 inches that seemed more like 7 feet) into a leather chair like crushed chiffon. She looked like a cross between Georgia O’Keeffe and a syncopated condor and spoke with talons for teeth.

“This isn’t going to be one of those ‘And then I wrote’ pieces, is it? I don’t like looking back. Let’s keep it crisp as lettuce.” She liked the result and sent me a dozen peonies in an old ice bucket with a note: “Bobbledy Boo Bop do Boo Bop do Bobbledy Bop … It’s Great–Love, Kay.” She never spoke to the press again.

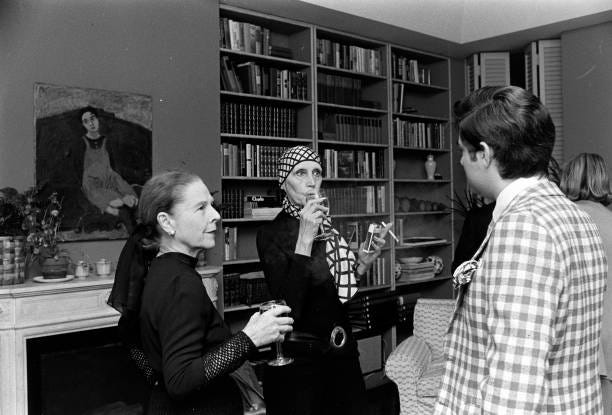

Kay didn’t give a fig about the past, but to explain why she was in a class by herself, a bit of background is necessary. The facts are not important because, like Diana Vreeland, she made them up as she went along. We do know she started playing jazz piano at the age of 4 and at the age of 15 performed Franz Liszt’s “Hungarian Fantasy” with the St. Louis Symphony, tripping over a potted palm on her way off the stage. At 17, she moved to California, changed her name from Kitty Fink, got a severe nose job and invented Kay Thompson.

She sang with Bing Crosby and the Mills Brothers, got fired from every job on radio and ended up in a pre-Broadway tour of Hooray for What , a political revue with songs by Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg, choreography by Agnes De Mille and direction by Vincente Minnelli. She sang a wistful song called “Poor Whippoorwill” and got sacked in Philadelphia. Years later, Harburg told me she was rotten. All I know is the humiliation hounded her throughout her life. She never trusted anyone again and never returned to the stage. Instead, she made one screen appearance in a 1937 Republic potboiler called Manhattan Merry-Go-Round , which, to quote Kay’s favorite one-line review, “chased its own tail on a one-way ride to oblivion.” She didn’t appear on the screen again for 20 years.

In the mid-40’s, as a vocal coach in the Rolls-Royce Arthur Freed Unit at M-G-M, she changed the sound of movie musicals. Frank Sinatra credited her with teaching him everything he knew about singing. She put the sob in Judy Garland’s voice. She made Lena Horne growl. In legendary musicals like Ziegfeld Follies , Good News and The Harvey Girls , she revolutionized the whole concept of group singing, incorporating bebop and jazz. Listen to the harmonies in “The Trolley Song” in Meet Me in St. Louis . Pure Kay Thompson magic. Everything she did was original. She influenced vocal groups like the Hi-Los. Nelson Riddle copied her harmonics in his orchestrations for Sinatra and Peggy Lee. In Judy Garland’s historic “Madame Crematon” number in Ziegfeld Follies , she introduced the first rap song, 40 years before Harlem did.

After work, she compiled special material for parties that everybody at M-G-M still remembers with awe. One night at a birthday party for her colleague Roger Edens, she created a breakneck tempo extravaganza called “Jubilee Time,” performed by Garland, Cyd Charisse, Peter Lawford and songwriter Ralph Blane, all dressed in costumes from Show Boat , and choreographer Robert Alton said, “Kay, I think you’ve got an act.” “What’s an act?” The world soon found out.

“After M-G-M, I had a headache for two years,” she said. “So I dragged in Andy Williams and his three brothers and we went on the road.” Walter Winchell called it the greatest nightclub act in history. On opening night at Le Directoire in New York, Constance Talmadge and William Randolph Hearst turned to Maurice Chevalier and asked him what he thought. “I don’t know,” he said, stunned, “I’ve never seen anything like it.” She rode the crest of success in posh watering holes like the Cafe de Paris in London and the Persian Room in New York. Then she got bored and another phase of her polka-dot career began.

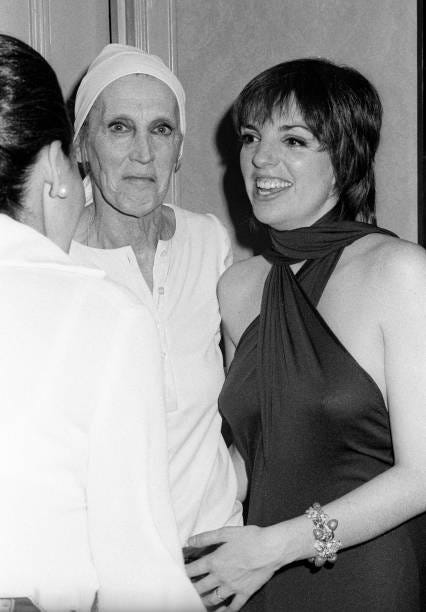

In 1955, the first of four Eloise books was born after fashion editor D.D. Ryan introduced her to illustrator Hilary Knight. The books were a sensation. The rumor that the precocious moppet left alone in the Plaza Hotel to fend for herself (“And charge it, please”) was based on Kay’s goddaughter, Liza Minnelli, is pure caca. Eloise was Kay herself, with an uncanny way of tapping into the kid in every grown-up.

As Eloise’s adventures spread to Paris, Moscow and Christmastime, Kay, restless again, abandoned the books and teamed up with her old friends at the Freed Unit, who moved to Paramount for one final fling at Hollywood’s golden age. Funny Face , now a milestone in musicals, had problems. Kay hated Fred Astaire. She also hated the Edith Head clothes. Audrey Hepburn was wearing Givenchy. Kay wanted something equally special, so she persuaded Roger Edens to call the egomaniacal, implacable Edith Head while she listened on the extension phone.

“Kay is playing a fashion editor based on Diana Vreeland,” he said, “so we need a wardrobe that is very Coco Chanel.” Dead silence, followed by, “Roger, go fuck yourself.” Kay said, “Don’t worry, I’ll do my own clothes,” and she did. When it came time for the “Clap Yo Hands” number with Astaire, she told Audrey, “I’m going to wipe the floor with that man,” and she did. In the film she made history with the flamboyant production number “Think Pink,” which was based on her own personal fashionoid philosophy.

When anyone asks what made Kay so special, Liza Minnelli says, “Once upon a time there was this amazing woman who could do anything, and once you saw her do it, it was too late to analyze what it was she did because she had already changed your life forever.” Her musical genius can be heard in the early Garland musicals, but rent Funny Face and you can see it.

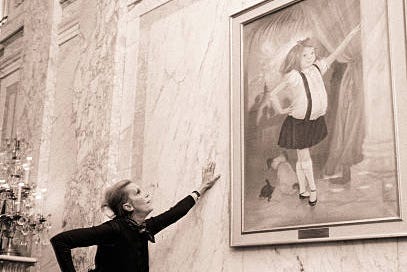

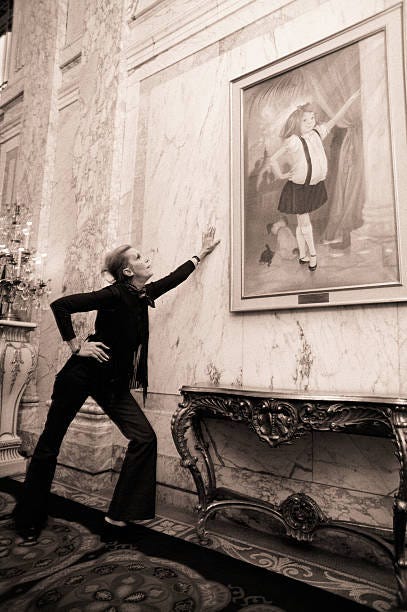

“Bobbledy Boo Bop do Boo Bop do Bobbledy Bop!” Shunning her triumph on the screen at last, she fled to a palazzo in Rome where she constructed a fake fireplace out of cardboard pinned together with zebra sheets from Porthault and lacquered her coffee tables with a case of nail polish. A cache of unfinished manuscripts, when last seen, was stored in a latrine in the garden. Back in New York, she established squatter’s rights at the Plaza Hotel and stayed for seven years without a bill. When the new management under Donald Trump kicked her out, the Eloise painting and Eloise postcards went, too. Now they’re back–a living testimonial for kids of all ages, to Kay more than to her 6-year-old alter ego. The day Judy Garland died, she took charge of Liza Minnelli’s life and apartment at 300 East 57th Street, where she sawed off the legs of the grand piano and covered it in red vinyl. Eccentric to the end, she spent the past 10 years in Liza’s penthouse on East 69th Street in a wheelchair, but her individuality and spirit were undiminished.

One Christmas, when we were both stranded in the city, we decided to dine together at my apartment. She never showed up, but sent over the entire dinner instead. At five minutes to midnight, she phoned to announce, with a sigh of relief, “Well, we got through that one, didn’t we?”

Kay on style was like Brooke Astor on manners. She staged Halston’s first fashion show in Europe in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles and taught Prince Albert of Monaco how to “sell” a song for a charity benefit. He told her he envisioned himself a singing bartender in a Third Avenue saloon and auditioned the tune. She listened and said, “I see. Remember the Hotel de Paris in Monte Carlo? That balcony overlooking the curve during the Grand Prix? You’re wearing a white tuxedo and a scarf. A silver Jag pulls up and out comes the most beautiful woman you have ever seen in a multicolored chiffon gown with a gardenia in her hair.” Prince Albert said he could see it perfectly. “Now sing it again.”

Her favorite costume was a prison uniform with four yards of red scarf wrapped around her neck. Sometimes she stopped traffic on Fifth Avenue wearing bones and turkey feathers. She rarely went out, but worked out at home with two one-pound dumbbells colored “hot titty pink.” Looking more like Louise Nevelson in her declining days, her beauty regimen was restricted to a pale light powder from Kenneth, Chinese lily pink lipstick and Ivory soap. Nutritionally, she fought the “monotony that has no place in a creative mind” with many sugar-free nibbles throughout the day–in the A.M., an egg and a slice of orange, then two hours later, two ounces of Gorgonzola and some cold roast beef with a chunk of grapefruit–”nothing much after 9 P.M. Maybe a peach before bed. Nothing heavy before sleep unless you want to dream about dock strikes.” In the end, she was living on nothing but Coca-Cola, but there was still a trumpet in her heart. She would forget the oddest things, like the name of Louis B. Mayer’s secretary at M-G-M, but she never lost her humor. Singer Jim Caruso remembers her leaving a message on his answering machine. After the part about how to leave a fax, her basso profundo responds impatiently: “You can very likely be faxed, but can you be fixed?” The last thing she said to Liza was “Take care of Eloise.” The last thing she said to Mr. Caruso before she died was “See you in the movies.”

She left behind a future fortune in Eloise royalties, a cult of movie fans who still sing “Think Pink” aloud during reruns of Funny Face , 40 pairs of shoes and a treasure of unpublished work including Darling Baby Boy , about her lavishly overindulged pet pug, whom we all suspect she killed by feeding him a diet of lime Chuckles, chocolate-covered cherries and braised livers in Marsala wine sauce. You couldn’t tell her, though. She would throw her hands in the air, shout “The drapes are on fire!” and leave the room.

“The best thing my mother ever gave me was Kay,” says a brokenhearted Liza Minnelli. “I thought she’d be around forever.” Bobbledy Boo Bop do Boo Bop do Bobbledy Bop! She was, but it wasn’t long enough.

© 1998 Rex Reed for the New York Observer