Peter Bogdanovich on Dietrich

Everything she does is done completely—there are no half-gestures or unfinished thoughts in her performance.

HOLLYWOOD

PETER BOGDANOVICH

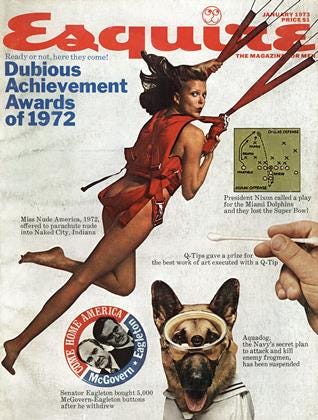

From ESQUIRE, January 1973

Marlene Dietrich’s taken your seats,” the assistant director was a little out of breath. “You don’t care, do you? She likes to sit in the first two on the right. They moved you guys behind her.” Ryan O’Neal and I were at Los Angeles International Airport with a few others of the cast and crew of Paper Moon, a movie we were flying to Kansas to shoot. I said we didn’t mind.

Ryan said, “Marlene Dietrich is on our plane going to Kansas?”

No, it turned out she was flying to Denver (we had to switch planes there) to give six concert performances at the Denver Auditorium. Hard to believe, but sure enough, there she was, sitting across from us at the gate, all in white—white-brimmed hat, pants, shirt, jacket—looking great and also bored and a little suspicious of the noisy good spirits around our group.

We went over to say hello. I introduced myself. Ryan said, “Hello, Miss Dietrich, I’m Ryan O’Neal. ‘Love Story.’” He grinned.

“Yes,” she said. “I didn’t see it—I liked the book too much. I won’t see The Godfather for the same reason— Brando is too slow for it anyway—why didn’t they use Eddie Robinson?”

There were several people I knew who had worked with and loved her, and I mentioned a few of them, trying to get a conversation going, but she was a little frosty, so we slipped away after a few moments. Ryan said, “I think we did great,” but I didn’t.

She was right behind us as we waited to have our hand baggage searched. We tried again; she was nicer this time. “I saw ‘The Last Picture Show,’” she said to me. “I thought if one more person stripped slowly, I would go crazy.” “Did you see ‘What’s Up, Doc?’” Ryan said. “We did that together.”

“Yes, I saw it,” she said and nothing more. I changed the subject—told her I’d recently run a couple of her old pictures—Lubitsch’s “Angel” and Von Sternberg’s “Morocco.” She made a face at the first and said the second was “so slow now.” I said I assumed Von Sternberg wanted it that way—he’d told me he had. “No, he wanted me slow,” she said. “On ‘The Blue Angel,’ he had such trouble with Jannings—he was so slow.” The luggage inspector was especially thorough on her bag—and she looked disgusted. “I haven’t been through anything like this since the war.”

On the plane she sat in front of us, with her blonde girl friday, and by now, she’d obviously decided we weren’t so bad; she spent almost the whole flight leaning backward over the top of her seat, on her knees, talking to us. And she was just swell. Animated, girlish, candid, funny, sexy, baby-talk “r” and everything.

I told her I was trying to stop smoking again. “Oh, don’t,” she said. “I stopped ten years ago and I’ve been miserable ever since. I never drank before—and now I drink. I never had a cough when I was smoking—now I cough. Don’t stop—you’ll get fat and you don’t want to do that.”

We talked about movies she’d been in and directors she’d worked for. After a while, it became apparent to her that I’d seen an awful lot of her pictures. “Why do you know so much about my films?”

“Because I think you’re wonderful and you’ve worked for a lot of great directors.”

“No,” she said it dubiously. “No, I only worked for two great directors— Von Sternberg and Billy Wilder.”

“And what about Orson?”

“Oh, well, yes, Orson.”

I guess she wasn’t so impressed with Lubitsch or Hitchcock or Fritz Lang, Raoul Walsh or Tay Garnett or René Clair. She looked amazed when I told her I liked Lang’s “Rancho Notorious,” amused that I enjoyed Walsh’s “Manpower,” confused that I was so fond of “Angel.” I had read somewhere that her own favorite performance was in Welles’ Touch of Evil. “You still feel that way?” I said.

“Yes. I was terrific in that. I think I never said a line as well as the last line in that movie—‘What does it matter what you say about people . . . ?’ Wasn’t I good there? I don’t know why I said it so well. And I looked so good in that dark wig. It was Elizabeth Taylor’s. My part wasn’t in the script, you know, but Orson called and said he wanted me to play a kind of gypsy madam in a border town, so I went over to Paramount and found that wig. It was very funny, you know, because I had been crazy about Orson—in the Forties when he was married to Rita and when we toured doing his magic act—I was just crazy about him—we were great friends, you know, but nothing. . . . Because Orson doesn’t like blonde women. He only likes dark women. And suddenly when he saw me in this dark wig, he looked at me with new eyes. Was this Marlene?”

"Well, he certainly photographed you lovingly."

“Yes, I never looked that good.”

“You had great legs,” Ryan said.

“Yah—great!” she grinned. “Great thighs!” She slapped one of them behind the seat.

“I dream about your legs and I wake up screaming,” said Ryan.

“Me too,” she said.

I asked her if she’d been upset about the late Josef Von Sternberg’s acerbic autobiography, “Fun in a Chinese Laundry,” in which he’d said that he had created her, and implied that she would have been nothing without him. (He’d once said to me, “I am Miss Dietrich— Miss Dietrich is me.”)

She pursed her lips, lifted her eyebrows slightly. “No—because it was true. I didn’t know what I was doing— I just tried to do what he told me. I remember in “Morocco,” I had a scene with Cooper—and I was supposed to go to the door, turn and say a line like, ‘Wait for me,’ and then leave. And Von Sternberg said, ‘Walk to the door, turn, count to ten, say your line and leave.’ So I did and he got very angry. ‘If you’re so stupid that you can’t count slowly, then count to twenty-five.’ And we did it again. I think we did it forty times, until finally I was counting probably to fifty. And I didn’t know why. I was annoyed. But at the premiere of “Morocco”—at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre—” she said the name with just the lightest touch of mockery —“when this moment came and I paused and then said, ‘Wait for me,’ the audience burst into applause. Von Sternberg knew they were waiting for this—and he made them wait and they loved it.”

I asked if he had gotten along with Cooper. “No—they didn’t like each other. You know, he couldn’t stand it if I looked up at any man in a movie—he always staged it so that they were looking up to me. It would infuriate him—and Cooper was very tall. And you know, Jo was not. I was stupid—I didn’t understand it then—that kind of jealousy.” She shook her head lightly, but at her own folly.

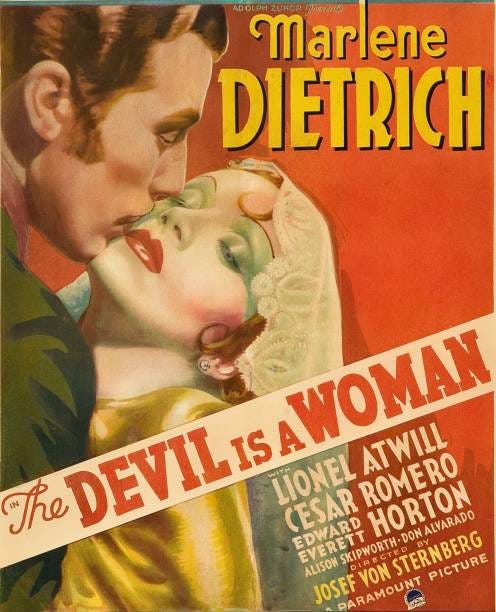

Which of her seven films with Von Sternberg was her favorite? “The Devil Is a Woman was the best—he photographed it himself—wasn’t it beautiful? It was not successful and it was the last one we did together—I love it.”

Ryan said, “I hear you’re a good cook.”

“I’m a great cook.”

“When’d you have time to learn?”

“Well, when I came to America, they told me the food was awful—and it was true. Whenever you hear someone in America say they had a great meal, it turns out they had a steak. So I learned. Mr. Von Sternberg loved good food, you know. So I would go to the studio every day and do what he told me, and then I’d come home and cook.”

I mentioned “Song of Songs”—the first picture she’d done without Von Sternberg—and said I didn’t like it very much. She agreed. “That was when Paramount was trying to break us up. So they insisted I do a picture with another director. Jo picked him—Mamoulian—because he’d made “Applause” —which was quite good. But this one was lousy. Every day, before each shot, I had the soundman lower the boom mike and I said into it so the Paramount brass could hear it when they saw the rushes, I said, ‘Oh, Jo—why hast thou forsaken me?’ ”

The next day—in my room at the Ramada Inn in Hays, Kansas—the phone rang. It was Marlene. “I found you.” She said it silkily and low. It was lovely and a little unnerving. We hadn’t told her where we were going so she must have done some tracing. “I got to my hotel last night,” she said, “and I missed you.”

“Me too. How’re you doing?”

She told me about a press conference she’d been through at the airport after we’d left. “I don’t think I made them very happy—but they ask such stupid questions. One old woman there —old—older than me—asked. ‘What do you plan to do with the rest of your life?’ I said to her, ‘What do you plan to do with the rest of yours?’ ”

We talked several times during the week, and she sent me a couple of warm and funny notes thanking me for the opening-night telegram and flowers and supplying anecdotes about the Denver performances: “I sang fine last night,” she wrote, “but I don’t think it was necessary. . . . Lights are bad ! They have no equipment. Poor country, you know !”

“How were the reviews?” I asked her on the phone.

“Oh, the usual—‘the legend’ and all that—you know—fine.”

On Saturday, Ryan and I and six others from our company flew to Denver for the night to see her show. I’ve never seen as mesmerizing a solo performance. She sang twenty songs, and each was like a one-act play, a different story with a different character telling it, each phrased uniquely and done with the most extraordinary command. No one has ever teased and controlled an audience better. “I’m an optimist,” she told them, “that’s why I’m here in Denver.” They loved her. How could they not. How could anyone not?

She transcends her material. Whether it’s a flighty old tune like “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby” or “My Blue Heaven,” a schmaltzy German love song, “Das Lied ist Aus,” or a French one, “La Vie en Rose,” she lends each an air of the aristocrat, yet she never patronizes. She transforms Charles Trenet’s “I Wish You Love” by calling it “a love song sung to a child” and then singing it that way. No one else now can sing Cole Porter’s “The Laziest Gal in Town”—it belongs to her. As much as “Lola” and “Falling in Love Again” always have. She kids “The Boys in the Back Room” from Destry Rides Again, but with great charm. Singing in German, “Jonny” becomes frankly erotic. A folk song, “Go ’Way from My Window,” has never been done with such passion, and in her hands, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” is not just an anti-war lament, but a tragic accusation against us all. Another pacifist song, written by an Australian, has in it a recurring lyric—“The war is over—seems we won”—and each time she sings it a deeper nuance is revealed.

Of course, she saw World War II at close range, entertaining the troops for three years, and it’s all brought back in her touching introduction to “Lili Marlene” which consists mainly of the names of all the countries in which she sang that song during the war. It called to mind what Hemingway had written in A Farewell to Arms: “There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of places had dignity. Certain numbers were the same way and certain dates and these with the names of the places were all you could say and have them mean anything. Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.” And that’s what Marlene conveyed; as she said, “Africa, Sicily, Italy, Greenland, Iceland, France, Belgium and Holland—Germany—Czechoslovakia,” her inflection carried with each a different untold story of what she’d seen, what the soldiers she’d sung for had seen. It was there in the way she did the song too. And suddenly you understood another thing Hemingway had written—this time about her—and you knew the soldiers must have understood it too when she sang to them those three long years: “If she had nothing more than her voice she could break your heart with it. But she has that beautiful body and that timeless loveliness of her face. It makes no difference how she breaks your heart if she is there to mend it.”

Everything she does is done completely—there are no half-gestures or unfinished thoughts in her performance. When she says Von Sternberg’s name, you know she is really thinking of him. And she never repeats an effect, doesn’t move much, just stands there and performs for you. Meticulously rehearsed, everything appears spontaneous, as though it were the first time she’d done it : a great showman—very theatrical—but subtle beyond praise. Let me be succinct. I fell in love.

After the show, still onstage, she saw that all the musicians and technicians got a drink, and thanked each one personally. She was particularly effusive about the local soundman. A short, middle-aged fellow, he came up shyly to say good-bye, and she embraced and kissed him lovingly, not the way I would guess it’s usually done in Colorado, or anywhere. The guy looked bewildered, thrilled, overwhelmed all at once; speechless as Marlene Dietrich hugged him to her and told him it was the best sound she’d ever had on the road. He wandered away with glazed eyes, a foolish grin—the happiest man in Denver.

In the dingy dressing room, her helpers were packing up. “Closing night is my favorite,” she said, “because I can call and cancel the insurance.” She sipped champagne, then picked up the only photo on her makeup table—a framed picture of Hemingway, the glass cracked, an inscription on it that read, “For my favorite Kraut.” She spoke to the photo. “Come on, Papa,” she said, “time to pack up again, huh? Okay, here we go.” And she kissed it. We were there, but it was a private moment. Proudly, she showed off a pair of ballet slippers she’d been given by the Bolshoi troupe, a sentiment in Russian carved on one sole, and some Scotch heather in a plastic bag—for good luck. “If you carry this with you, it means you will come back.” And a stuffed black doll she picked up gingerly. “Remember this—from The Blue Angel.”

We all ate at Trader Vic’s and she told stories and unwound from the show. She called Ryan her “blond dream-friend” and said she’d have to look at Love Story now. The next morning she came downstairs to see us off, stood at the hotel entrance in her slacks and shirt and cap watching us pull away, looking sorry to see us go—as sorry as we were to leave.

She gave me an envelope as we left. In it were two pieces of hotel stationery —on one she’d written out a quote from Goethe: “Ach, Du warst in längst vergangenen Zeiten—meine Schwester oder meine Frau.” On the other her own “literal” translation: “Oh, you were in long passed times my sister or my woman.” You too, dear Marlene, for me and all of us. Thank you.

©Esquire 1973