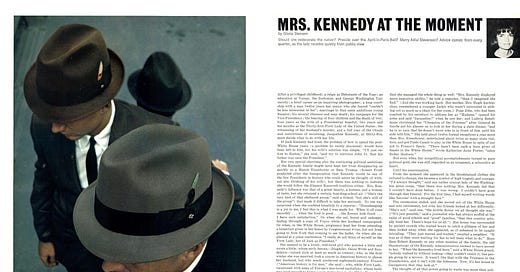

Mrs. Kennedy at the Moment

Should she redecorate the nation? Preside over the April-in-Paris Ball? Marry Adlai Stevenson? Advice comes from every quarter, as the lady recedes quietly from public view

Esquire

October 1964

By Gloria Steinem

AFTER a privileged childhood; a reign as Debutante of the Year; an education at Vassar, the Sorbonne, and George Washington University; a brief career as an inquiring photographer; a long courtship with a man twelve years her senior who she feared “couldn’t be less interested in me”; marriage to that same ambitious young Senator; his several illnesses and near death; his campaign for the Vice-Presidency; the bearing of four children and the death of two; four years as the wife of a Presidential hopeful; two years and ten months as the Thirty-first First Lady of the United States; the witnessing of her husband’s murder, and a full year of the rituals and restrictions of mourning, Jacqueline Kennedy, at thirty-five, must decide what to do with her life.

If Jack Kennedy had lived, the problem of how to spend the post-White House years (a problem he rarely discussed) would have been left to him, but his wife’s solution was simple. “I’ll just retire to Boston,” she said, “and try to convince John Jr. that his father was once the President.”

Her own special charisma plus the continuing political ambitions of the Kennedy family might have kept her from disappearing as quickly as a Mamie Eisenhower or Bess Truman (Robert Frost predicted after the Inauguration that Kennedy would be one of the few Presidents in history who could never be thought of without also thinking of his wife), but there was nothing to indicate she would follow the Eleanor Roosevelt tradition either. Mrs. Kennedy’s influence was that of a great beauty, a hostess, and a woman of taste, but she retained a certain boarding-school air (“She’s the very best of that sheltered group,” said a friend, “but she’s still of the group”) that made it difficult to take her seriously. No one was surprised when she confided breathily to a reporter: “Housekeeping is a joy to me, I feel this is what I was made for. When it all runs smoothly . . . when the food is good . . . the flowers look fresh . . . I have such satisfaction.” Or when she sat, bored and unhappy, leafing through a copy of Vogue while her husband campaigned. Or when, in the White House, pregnancy kept her from attending a breakfast given in her honor by Congressional wives, but not from going to New York that evening to see the ballet. Or when she explained at a press conference, “I really do not think of myself as the First Lady, but of Jack as President.”

She seemed to be a lovely, well-bred girl who painted a little and wrote a little; whose early heroes—Diaghilev, Oscar Wilde and Baudelaire—valued style at least as much as content; who, in the first winter she was married, took a course in American history to please her husband, but who much preferred eighteenth-century France (“American history is for men,” she said); who, while First Lady, vacationed with some of Europe’s less-loved capitalists; whose taste was good enough to bring a rare distinction to the White House, but no more eclectic than polite society would allow; who was, in short, the most worthwhile kind of ornament.

Sometimes, being apolitical was an asset. After a few halfhearted denouncements for her lack of involvement in women’s peace groups, even the Soviets left her alone. White House correspondent Marianne Means described the galvanic effect she had on anti-American Venezuelan farmers “by appearing like a vision in a lime sheath and greeting them with a warm, simple speech in Spanish.” The President was proud of “her concentration on giving historical meaning to the White House furnishings,” and a little surprised that she managed the whole thing so well: “Mrs. Kennedy displayed more executive ability,” he told a reporter, “than I imagined she had.” (And she was working hard. Her mother, Mrs. Hugh Auchincloss, remembered a younger Jackie who wasn’t interested in picking out so much as a chair for her room.) Pope John, who had been coached by his secretary to address her as “Madame,” opened his arms and said “Jacqueline!” when he saw her; and Ludwig Bemelmans christened her “Cleopatra of the Potomac” after General de Gaulle put his glasses on to look at her during a state dinner, “and he is so vain that he doesn’t know who is in front of him until his aide tells him.” She held about twelve formal receptions a year more than Mrs. Eisenhower, entertained about twice us many state visitors, and got Pablo Casals to play in the White House in spite of our aid to Franco’s Spain. “There hasn’t been such a born giver of feasts in the White House,” wrote Katherine Anne Porter, “since Dolley Madison.”

But even when her nonpolitical accomplishments turned to pure political gold, she was still regarded as an ornament, a salonnière at heart.

Until the assassination.

From the moment she appeared in the bloodstained clothes she refused to change, she became a symbol of high tragedy and courage. “I’d always thought,” said one rather cynical lady of the Washington press corps, “that there was nothing Mrs. Kennedy did that I couldn’t have done better. I was wrong. I couldn’t have gone through that funeral. For the first time, I find myself writing words like ‘heroine’ with a straight face.”

The ceremonies ended, and she moved out of the White House and into retirement, but even her friends looked at her differently. “She’s not,” said one, “the brittle flower we all thought she was.” (“It’s just possible,” said a journalist who had always scoffed at the value of good schools and “good” families, “that this country actually bred her. There’s hope for us all.”) Her house was surrounded by patient crowds who waited hours to catch a glimpse of her and then looked away when she appeared, as if ashamed to be caught intruding. “They just waited and waited,” recalled a neighbor. “It was as if they were waiting for her to tell them what to do.” More than Robert Kennedy or any other member of the family, the odd thaumaturgy of the Kennedy Administration seemed to have passed to her. “When the Kennedys lived here,” said a White House guard, “nobody walked by without looking—they couldn’t resist it, like people going by a mirror. It wasn’t like that with the Trumans or the Eisenhowers, and it isn’t with the Johnsons. Now, it’s her house in Georgetown that they look at.”

The thought of all that power going to waste was more than politicians could bear. Her year of mourning included wearing black and canceling all public appearances and official functions, but within a month after the assassination Mrs. Kennedy’s future was being discussed nearly as much as President Kennedy’s past. Dean Rusk suggested that she become a touring Goodwill Ambassador, and a Michigan lady legislator passionately advocated her appointment as Ambassador to France, though the “biggest problem might be that . . . other nations might want someone of the same caliber.” Clare Boothe Luce, with the questionable sincerity of a Goldwater Republican advising a Democrat, wrote an article proposing that Mrs. Kennedy rise to the podium at the Democratic Convention, make a dramatic plea, and force the delegates to give Robert Kennedy the Vice-Presidency. A politician from Boston suggested that Mrs. Kennedy be Vice-President herself. Civil-rights leaders spoke of her becoming a kind of good-looking Eleanor Roosevelt who would lead Negro children into school, and give fireside, mother-to-mother talks on integration; and a few liberals daydreamed aloud, without much hope, that her marriage to Adlai Stevenson might make him a candidate again. Politicians who feared the power of her endorsement advised that she retire, as widows of other Presidents have done, or stick to culture, or, at the most, run an international salon. Even those who thought her power was more moral than political had ambitious plans: an international newspaper column, a weekly show on Telstar, a campaign to beautify America, a foundation to aid young artists, an appointment as head of UNESCO.

The thought of all that power going to waste was more than politicians could bear.

In a pre-assassination article comparing the role of Mrs. Kennedy, then in the White House, to that of Mrs. Roosevelt, sociologist Margaret Mead wrote: “American society accords far greater leeway to widows than to wives—even permitting them to carry on activities initiated by their husbands, in whose shadows they were supposed to live quietly as long as their menfolk were on stage.” The same Mrs. Kennedy who had been dismissed as an ornament was being urged to be a leader.

“This November twenty-second, when her retirement is over,” said a State Department official, “Jackie could become, if she wanted to, the most powerful woman in the world.”

In contrast to the attention lavished on her, the life Mrs. Kennedy was living in retirement seemed to be very simple, or at least very private. Newspapers, desperate for news of her, ran front-page photographs of her walking the dog, taking her daughter to school, or her son to his play group. Books and one-shot magazines on her life sold by the millions—Jacqueline Kennedy: From Inauguration to Arlington, and Jacqueline Kennedy—Woman of Valor (Her Dreams As A Girl, Her Prayers As A Woman, Her Fears As A Mother)—and a nationwide poll showed that she was the most admired woman in the world. On the suspicion that she might have been pregnant when the President died, at least one magazine delayed a special issue for months, and gave up only after she was photographed in ski clothes in late March. Time, Life and Newsweek wrote all they could find out about her daily routine which, minus the adjectives and padding, boiled down to the fact that she saw the children in the morning, answered correspondence or worked on plans for the Kennedy Library, played with the children in the afternoon, and sometimes had dinner with friends. The cover of a television semiannual promised “Jacqueline Kennedy: Her Future in TV” (the article said she didn’t want one), and a movie magazine headlined “The Men Who Love Jackie Kennedy” (they turned out to be Lyndon Johnson, Dean Busk, and others who had paid her sympathy calls). When she took John Jr. to a horse show where he was to ride his pony in the lead-line class, well-bred society ladies crowded around in an effort to hear what she was saying to her son. One finally managed it and reported back. What Mrs. Kennedy said was, “Keep your heels down.”

Reporters were notified of what her press secretary, Pamela Turnure, called “milestone occasions”—visits to the President’s grave with foreign dignitaries, an occasional appearance for the Kennedy Library, her appointment by President Johnson to the White House Preservation Committee—but the rest of her life was, as Miss Turnure said, “pretty insulated.” She was surrounded by her protectors: all the members of the Kennedy family plus such old friends as artist William Walton, British Ambassador Sir David Ormsby-Gore and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Ben Bradlee, Secretary of the Treasury Douglas Dillon and his wife, Franklin Roosevelt, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. Charles Bartlett, Secretary of Defense and Mrs. Robert McNamara, Michael Forrestal, and others.

“We all invited her to small dinners,” explained one of that group, “but no matter which one of us gave it, the guest list was always pretty much the same—all friends from the old days—and the conversation always ended in reminiscing.”

In the beginning, visitors noticed that her only photograph of the President was one taken while he watched a ceremony on the White House lawn shortly before he died. It showed him from the back. But, by midwinter, she was able to go through her husband’s mementos to select “things I hope will show how he really was” for a touring exhibit, and to watch The Making of a President, a private screening of a television documentary of the 1960 campaign. (A witness said she looked teary, but “When the film showed Kennedy making wisecracks, she laughed. When he made serious points, she nodded in agreement.”)

Still the small dinners continued. (“I never liked them too much before,” she said frankly, “and I like them even less now.”) Those close to her who felt she should be distracted as well as protected—especially her sister and almost full-time companion, Lee Radziwill—invited outsiders to entertain her, but the new guests were often so fearful of saying the wrong thing that they hung back and said nothing at all. A man described as a “young embassy type” spent an evening as her partner, and found himself reduced to asking politely if she had ever seen a bullfight. (“You just can’t go through all that again,” observed a guest. “It was like being right back at college.”) A New York journalist who sat next to her at dinner found her starved for information. “She wanted to know if Richard Burton’s Hamlet was good,” he said, “and what Shepheard’s was like, and which of several current books were worth reading and wouldn’t make her sad.”

By way of distraction, Mrs. Radziwill invited movie producer George Englund to stop in for a drink and some discussion of a Kennedy Foundation Dinner, on which he was an adviser. For further distraction, Mr. Englund brought along one of his actors, Marlon Brando. The three decided to go out for dinner, and asked Mrs. Kennedy to come along. (“It was very simple and spur-of-the-moment,” explained Pamela Turnure. “They just didn’t want to leave her there alone.”) They chose what was later described by the press as “an Embassy Row Restaurant,” The Jockey Club, because it was the only one in which Mrs. Kennedy, during her three years in the White House, had been able to have a private, reporterless meal. (She had lunched there with John Kenneth Galbraith, then Ambassador to India, at the President’s suggestion.) But this time it was not so private. Newspaper reporters were everywhere, Brando inquired about backstairs escape routes, and the restaurant manager offered to loan them his car, but it was too late. The story—down to the fact that Brando “smiled slightly as he lit cigarettes”—was carried by newspapers here and abroad.

The fact that she had chosen to make her first social appearance since the assassination with Mr. Brando (which was pretty much the way the no-explanation newspaper report made it appear) lifted the lid on other criticisms. And among those who believed that John F. Kennedy had not yet proven himself as a President, or that the Kennedy family was using the country’s grief to continue its power, or that its power was not being used to advance the right causes, or that Mrs. Kennedy should have invited them to one of those small dinners, there had been a kind of underground current of criticism for some time.

That both Kennedy and Lincoln had been assassinated, for instance, was regarded as too small a basis for their identification; and some critics felt there was a clear and faintly sinister effort to identify them. (On her return from Dallas with her husband’s body, Mrs. Kennedy had asked Chief-of-Protocol Angier Biddle Duke to find out how Lincoln had been buried, and the precedents he discovered during an all-night investigation were used as guideposts for the Kennedy funeral. Later, she arranged to have a Kennedy inscription added to that in the Lincoln Bedroom of the White House.) There was some resentment of the Eternal Flame she requested for his grave. When schools, bridges, airports, Cape Canaveral, a fifty-cent piece, and the National Cultural Center took on the Kennedy name, resentment grew. Fund raising for the Kennedy Library, the Telstar program celebrating what would have been Kennedy’s forty-seventh birthday, the touring exhibit of Kennedy memorabilia, and the designation of his Brookline birthplace as a National Historical Landmark were all greeted as new proofs of excess.

One Washington newspaperman insisted that Kennedy himself—like the Roman Emperor who said on his deathbed, “I fear they will make a god of me”—would not have approved.

Not all the criticism was directed at Mrs. Kennedy. Some felt that the political ambitions of the Kennedy clan made them more her exploiters than her protectors; and others were apprehensive that the family’s continuing devotion, however well-meaning, would bolster the group that Washington columnist Mary McGrory had dubbed “the Kennedy irreconcilables,” and make the new Administration’s work more difficult. Robert Kennedy had tried to slow down the epidemic of renaming, and his sister-in-law had said in her first public statement that it was time people paid attention to the new President and the new First Lady, but, to some, those efforts seemed insincere or not enough.

The same Mrs. Kennedy who had been dismissed as an ornament was being urged to be a leader.

Some complaints were more picayune. When, on January fourteenth, Mrs. Kennedy made her first television appearance to thank the thousands who had sent messages of sympathy, it coincided with Mrs. Johnson’s first White House dinner. As a result, newspapers were full of Mrs. Kennedy and printed little about the dinner. Ladies of the Washington press corps grumbled about Mrs. Kennedy’s thoughtlessness, but no one could determine who had planned what first.

President Kennedy was thin-skinned to political criticism but not to personal barbs. (A writer for a national magazine recalled his reaction to a rumor, printed by Dorothy Kilgallen, that Jackie was not really pregnant during the 1960 campaign but was being kept under wraps for political reasons. “He just laughed about it,” said the writer, “and added a few amusing comments of his own about what one could expect from that quarter.”) For Mrs. Kennedy, the areas of sensitivity seemed to be reversed. She was disturbed by the incident of the Brando dinner and took time to explain to friends how it happened, but she seemed perfectly confident of the ways in which the President’s memory would be served best. (“She’s less upset by those criticisms than her staff is,” said Pamela Turnure. “Once she decides something is right, she just does it.”) For a woman whose combativeness, while First Lady, was usually limited to writing letters to Women’s Wear Daily protesting the hard time given her by that trade paper about where and how she bought her clothes, Mrs. Kennedy was remarkably tough-minded in the face of charges that she was overestimating her husband’s historical influence. “He changed our world,” she said firmly, “and I hope people will remember him and miss him all their lives.”

“She’s not political,” explained a former Kennedy adviser, “but she is immensely loyal. She didn’t like campaigning or being a political wife, but she did it because it mattered to Jack. If he hadn’t become President, it would have taken him a while to recover; the whole force of his tremendous energy was concentrated on that goal. If Jackie hadn’t become First Lady, she would have smiled gently and said, ‘All right. What do we do now?’ ”

Her loyalty was transferred to her protectors, especially to Robert Kennedy. (He is, as she explained in a now-famous quote, “the one I would put my hand in the fire for.”) As a nondriver can relax with someone else at the wheel, Mrs. Kennedy seemed able to act on the political counsel of her protectors and not worry about it.

Her controversial “endorsement” of former Press Secretary Pierre Salinger, then running in California’s Democratic State primary, was given at Salinger’s request, but only with Robert Kennedy’s permission. There had been a suggestion that she do more than make a statement: under the guise of spending a few days at Elizabeth Arden’s “Maine Chance” beauty farm in Arizona, she was to make a personal appearance in the campaign. (“There was a point there,” said one of his supporters, “when Pierre was really worried that he wouldn’t make it.”) The trip was turned down on the grounds that the public appearance would be inappropriate. (“Can you see Jackie,” said an amused friend, “at Maine Chance?”) Instead, a telephone interview was granted to California newspaperman Robert Thompson, and the result for Salinger was a helpful statement that “President Kennedy valued his advice and counsel on all major matters.” Reportedly, Robert Kennedy approved her giving that support only after it was apparent that Salinger was, in effect, running as a Kennedy. (His slogan was, “Let the man who spoke for two Presidents speak for you,” and his staff sent out 4,000,000 postcards bearing a photograph of President Kennedy, the words, “In His Tradition,” and a sample ballot with an “X” after Salinger’s name.) But getting her to do it seemed to take very little persuading. “She feels it’s natural,” explained a writer friend of the Kennedys, “to serve her husband’s memory by helping his men, the men who will carry on his work. I’m sure she’ll keep right on doing it, but of course only if Bobby says so.”

Shortly before moving to New York, Mrs. Kennedy apologized for not allowing a picture magazine to do a story on her children. She was sorry to be difficult, she said, but she really hoped her children could grow into their teens without publicity. The editor pointed out that a photograph of Caroline and John Jr. with Robert Kennedy and his children had recently appeared on the cover of Life. “Oh,” she said, and smiled, “but that was for Bobby.” In their temperament and background, Mrs. Kennedy and her brother-in-law have very little in common. (A recent guest at a Kennedy family dinner noted that they had nothing to talk about. “They share a common loss and a basic kind of guts,” he said, “and that’s about it.”) But Robert Kennedy is head of the family now, and Mrs. Kennedy—who instructs her children that “Kennedys don’t cry”—seems determined to be loyal.

Her sister, Lee Radziwill, three and a half years younger, often serves as a lightning rod for social criticism of Mrs. Kennedy in much the same way that Robert Kennedy, on political issues, often did for his brother. Any association with so-called frivolous social types (i.e., The Best-Dressed List, The Jet Set, Marlon Brando or Europeans who don’t work) as opposed to worthwhile friends who befit a First Lady (i.e., André Malraux, John Steinbeck, Members of the Cabinet, and Americans who work) has been blamed, traditionally, on Mrs. Radziwill. As a doyenne of Paris fashion, a sometime expatriate, and the once-divorced wife of a Polish prince, she is generally regarded as the representative of café society in the woodpile.

“Lee is what Jackie would have been if she hadn’t married a Kennedy,” explained one intimate, “a charming, witty, intelligent woman who, as the daughter of a rich stockbroker, never acquired much experience of real life or much social conscience.” Another theory is that the existing difference between the sisters was only dramatized by their choice of husbands, that Mrs. Kennedy always had been more frank and serious-minded. But they are loyal to each other. (After their joint trip to India in 1963, Mrs. Kennedy said her sister had been “marvelous. . . . I was so proud of her—and we would always have such fun laughing about little things when the day was over. Nothing could ever come between us.”) “They’ve been through a lot together; their parents’ divorce, their mother’s remarriage and all that,” said an old friend. “When the chips are down, it’s still the Bouvier girls against the world.”

It was partly due to her sister’s urging that Mrs. Kennedy decided to leave the Georgetown house with the perpetual crowds outside. She spent more and more weekends in New York, and the press tried vainly to trace her movements. (“When something is published about one of them,” explained an anonymous friend, “it’s a game with the Kennedys to figure out who told.”) She was seen inspecting a cooperative apartment on Fifth Avenue, having lunch with novelist Irwin Shaw, talking to cartoonist Charles Addams at a dinner party, walking on Madison Avenue, and going to church at Bedford Hills, New York. A local newspaper reporter spent much of that Sunday phoning around to the country homes of well-to-do Manhattan families, including that of Mr. and Mrs. James Fosburgh (whom President Johnson had appointed to the White House Preservation Committee), where Mrs. Kennedy was spending the weekend. He also phoned Broadway producer Leland Hayward and his wife—with whom Mrs. Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Bennett Cerf, Truman Capote and others had just had lunch—but no one told. It was difficult for her to be anonymous anywhere, but clearly it might be a little less difficult for her and her children in New York.

In July, Mrs. Kennedy announced that her Georgetown house, whose redecoration she had halted a few months before, and Wexford, her Virginia estate, were being put up for sale. The Washington Post regretted “losing a longtime resident and foremost tourist attraction.” “She came among us like some wildly unexpected fairy queen,” wrote The Washington Star, “and with her goes the heart of everyone who had lived in this place when she did.” She was breaking her initial resolve to “live in the places I lived with Jack . . . Georgetown, and with the Kennedys at the Cape,” and New York rejoiced.

“Of course, the social echelons are excited,” said society press agent Mrs. Stephen Van Rensselaer Strong. “Her presence is a signal honor and will have primary salient impact; she would make any party.” “She’ll dress up New York,” said a fashion writer. “People will go more formally to the good restaurants and theatres because she might be there. It will be chic to be cultural.” A spokesman for the Gray Line New York Tours promised that buses would not go off their routes to pass her apartment, “but I see no reason why, if it’s on the route, our guides—we call them lecturers— shouldn’t point it out.” A rumor that east-side bookmakers were taking bets on Mrs. Kennedy’s choice of a school for her daughter was squelched by the news that it was a sure thing: “She’s enrolled in the second grade at the Convent of The Sacred Heart on Ninety-first Street,” said an alumna; “just think how many tickets we can sell for our benefit next year!” With the exception of a few dissenters (a querulous writer in the “Voice of the People” column of the Daily News wanted to know “what part of . . . Harlem she will live in as a symbol of her husband’s civil-rights bill”), New Yorkers were pleased to receive her, if for rather selfish reasons. But Mayor Wagner was optimistic. “We will give her every opportunity,” he said stoutly, “to have as much privacy as she wants.”

In anticipation of her emergence into public life in November, some large charity events have already been postponed. (The December benefit performance, in Washington, of My Fair Lady was rescheduled in the hope that she could come. It is for the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts: Mrs. Kennedy is one of the patrons.) Her social secretary, Nancy Tuckerman, has so many requests for Mrs. Kennedy to be sponsor or honorary chairman of charity-social events that she can’t list them all. New York hostesses who are not optimistic enough to think that she will come to their parties (“The competition,” said one, “is going to be absolutely cutthroat”) are trying to spot in advance the functions she might attend. (Any Lincoln Center benefit, any premiere sponsored by the Kennedy Foundation for Retarded Children, the Polish Ball, the National Horse Show, and the Convent of The Sacred Heart’s alumnae benefit are the current favorites.)

“I hope,” remarked Glamour editor Kathleen Casey, “that she has some good advisers and serious friends, because she’s going to be set upon by café society and social climbers who will try to attach themselves to her just as they did to the Windsors.”

In fact, Mrs. Kennedy has been surrounded by friends, serious and otherwise—by exploiters, distractors who vie to amuse her, and protectors who insulate her from the world—for much of her life, but she is, as William Walton said, “a strong dame.” She has survived. “Jackie has always kept her own identity,” said Robert Kennedy admiringly, “and been different.”

Married to a strong-willed man twelve years her senior, plunged into the Kennedy clan and the role of Senator’s wife at twenty-four and the White House at thirty-one, Mrs. Kennedy was often in danger of being submerged. (“I feel,” she said after her husband’s election, “as though I have just become a piece of public property.”) She was so uncertain of being able to remain “a private person” that she rarely cooperated with a press who, for the most part, adored her (she signed a photograph to Pierre Salinger, “from the greatest cross he has to bear”), and once disguised herself in a nurse’s uniform and a wig in order to take her daughter out unnoticed. Some of the journalists who went along on her Indian trip had also accompanied Ethel Kennedy and Queen Elizabeth, and they complained that they had got to know “not only Ethel, but the Queen much better than Mrs. Kennedy.” A writer who was a personal friend managed to get a few words with her only on the plane going home, and a photographer commented that “She barely said hello to any of us; it was hot as hell and she didn’t sweat or let a hair get out of place; she didn’t feel well through much of the trip but she never showed it; she was playing the great lady and total stoic.”

Yet, at the end of the trip, she saw each newspaperwoman individually and presented her with a note of appreciation and a hand-painted box she had picked out herself. And on the last days NBC reporter Barbara Walters remembered that she relaxed for the first time, as if she had been let out of school: “We met the camel driver whom Lyndon Johnson had invited for a visit, and someone asked if Mrs. Kennedy would like to ride the camel. She was hesitant about it and said, ‘No, but Lee would.’ Her sister said something like ‘Thanks a lot.’ It was the first time we had seen that kind of banter between them, and it was obvious that they really liked each other’s company. When Lee got off, Mrs. Kennedy got on, riding sidesaddle with her skirt up over her knees. She looked kiddish and charming and as if, finally, she was relaxed and enjoying herself.”

Much of the demure, soft-voiced image she presented as she sat, hands folded and immobile through countless public functions, was evidence of the seriousness with which she took her role as First Lady. (“I’m getting good at it,” she said. “I just drop this curtain in my mind. . . .”) The pose concealed shyness, but it also hid a sharp wit—“It’s the unexpectedness of it,” said John Kenneth Galbraith, “that makes her so fascinating”—and a strong will—“I wouldn’t dream of telling Jacqueline what to do,” said her mother; “I never have.” At her first press conference after the election, Mrs. Kennedy apologized, with a touch of whimsy, for being unable to speak “Churchillian prose,” but when a reporter asked a little condescendingly if she thought she could do “a good job as First Lady,” her reply was firm. “I assume,” she said, “that I won’t fail [him] in any way.” Referring of course to her husband.

An interesting case might almost be made for the transference of some of the President’s qualities. Robert Kennedy—who was always “the active one while Jack was the sick kid who read the books”—has taken to reading political theory and quoting Thoreau and Emerson. Ted Kennedy—the gay, slightly pampered one—is convalescing with a painful back injury and is said to be using the time to research a book. For Mrs. Kennedy, the change seems to be in attitude: she has acquired a new sense of history and a sense of her own place in it. (“Once, the more I read of history, the more bitter I got,” she told writer Theodore H. White. “For a while I thought history was something that bitter old men wrote. But then I realized history made Jack what he was. . . .”)

The change is not so great that she plans to accept any formal political responsibility: she has limited herself to work having directly to do with her husband’s memory. Her children are still her first concern. (“I was reading Carlyle,” she once told a reporter, “and he said you should do the duty that lies nearest you. And the thing that lies nearest me is the children.”) She is no longer the dilettantish Bouvier girl, and New Yorkers who hope she will become the center of a glittering social scene are likely to be disappointed. She still has no real interest in politics or activism, but if she or her advisers feel that her role calls for her to act politically, indications are she will do it.

“Her public and private images of herself,” explained a former classmate, “are not as different as they used to be. After a few years on her own—if she can survive all the problems and pressures—she just might emerge as the person who, up to now, only her friends have known.”