Marian Seldes and Julie Harris on Laurette Taylor

"She was the dream of the 'real' actress. You see glimpses of her, but nothing, nothing like her."

The filmmaker Rick McKay once told me that the single performance most often referenced in his many interviews with theatre luminaries was that of Laurette Taylor in Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie. McKay, who gave us “Broadway: The Golden Age, by the Legends Who Were There,” from 2004, shared with me the memories of those who had seen Taylor’ performances, along with the laments of those who had missed it—by chance, by making an unwise decision, or, as with most, by not having been born yet.

I had the good fortune to speak with two actresses who saw Laurette Taylor in The Glass Menagerie, and they were kind enough to speak to me at length.

MARIAN SELDES

“The problem—for me—in talking about acting is that it doesn’t make much sense. It becomes a jumble of adjectives, and I don’t think anyone has any idea of what you saw, what they missed, what was special. What does touching mean? To you? To me? To anyone? Staggering is a word that gets tossed about now about things. A staggering novel. A staggering film. A performance that left me staggering. What does that mean? I stagger for reasons entirely unlike those that may affect you.

“When I would talk to students, I would talk about effects on the stage. A lot of what Sanford Meisner used to call ‘as if’ moments. For me, Laurette Taylor moved about the stage ‘as if’ she were a sort of fever chart, or a series of musical notes. I felt that Tennessee had written a chamber piece, and the characters were musical notes moving about, and Laurette’s Amanda was the most mutable. We talk now of manic behavior, and I’ve seen people behave in a way where their moods shift quickly, and you see a dramatic alteration of face and voice, and that’s what Laurette did. Could do.

“When I talked to students, I would tell them to look at people whenever they could. To really watch them. To remember moments in their lives when people behaved in certain ways. Maureen Stapleton talked once about a mother whose child had died—I don’t remember how; I think a sudden accident—and she could never forget the sound of the scream she made. It was terrifying. People ran out and saw her, and she was literally mad—driven mad—by the shock and the grief. Maureen said she used this sound—or tried to—for Tennessee’s The Rose Tattoo. Now, here is an actress taking a memory and applying it to a part she has learned, to which she is dedicated. Grief is very personal and very specific. When we see bad acting, it is usually because a poor or lazy actor has just applied an emotion, an adjective—like a veneer or a coat of makeup—over the face and movements. It isn’t felt. It doesn’t derive from memory and imagination. Maureen didn’t try to imitate that woman: She applied the memory of the sound, the memory of the event, to her particular voice; her character’s particular reaction. Maureen’s character has lost her husband in that play, and there were complicated emotions at play: He cheated; he may have been distant or abusive. But she loved him passionately. They enjoyed a sexual joy, what Harold Clurman called a ‘regular and lubricated rapprochement.’ So the anger evaporates. Loss sets in. A lacuna, a vacuum, opens up and we can imagine that, and so the scream sounds a particular way. It’s coming from a unique emotion from a unique person.

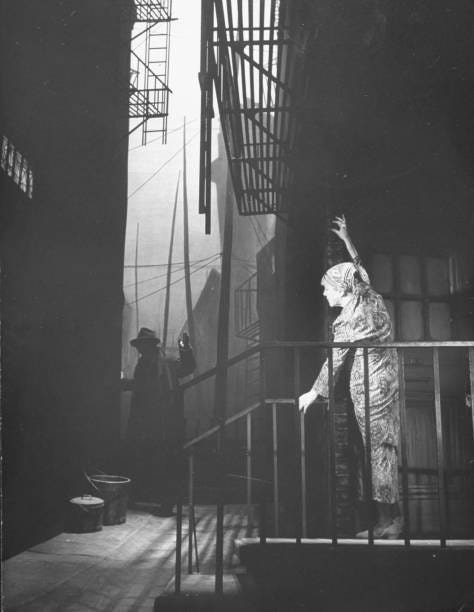

“So Laurette did this. I can’t imitate it. Well, I could, but it wouldn’t be good. It wouldn’t be based on anything other than my memory of the performance. It’s not the best representation of what she did. Instead, I remember someone I knew who experienced grief in such a way that it appeared as if weights had been applied to her ankles. She was not an old woman, and she didn’t walk like a woman who was arthritic or wary or afraid of losing her balance. It is a perfectly unique way of moving, and I’ve seen it since so many times, and I know immediately that someone is operating beneath and alongside so much grief or worry—some sort of emotional weight. Laurette did this, but then when there was an opportunity to sell a subscription or to arrange—at great and crippling expense—an evening for her daughter, she became antic. Spritely. Age fell from her face. Nothing about it was artificial, and you’ll hear people talking as if they were eavesdropping on someone in a private experience. Listening at a door. Peering through a window. Reading someone’s diary. See, already, I’m going into descriptions that sound trite and don’t reveal what Laurette did. I can only give an idea.

“When I would tell students to look at people, I knew it was hard for them to remember. They were young and starting their lives. They were going to see things and dating and having adventures. Fine, I would tell them, but look at everything. In every situation, including those in which you have a part. Actors need to be—and usually become—so sensitive to emotions that they can tell when someone is lying. To them or to others. A sort of extrasensory perception arises, and I’ve seen people on the bus or on the street, and I almost feel that I know just what they’re thinking and going through. I remember going to see Patti Lu Pone in The Woods. [A play by David Mamet that was done at Second Stage in 1982, where Marian saw it.] I had worked with Patti so much, and I had so much respect for her, and even as I felt I could see how she applied so much to her part, I was still not prepared for the effect it had on me. Patti has an ability to allow us to feel that we have witnessed an emotional autopsy on her. She is unafraid to just expose herself, and in that play she was both angry and distorted by this emotion, and then resplendent in her love and joy. I felt at one point that I was witnessing her having a real orgasm on that stage, and perhaps I was witnessing her memory of pure ecstasy, which she pushed out from her being. I have always loved how Patti looks, but there was a moment in that play in which she became resplendent. It was like she had a dozen light bulbs inside of her, and they all switched on at the same time. I’m not going to ask Patti what she was thinking, what she was applying, but I will never forget that performance.

“Laurette had a similar impact on me. You felt her disappointment, rage, joy, giddiness. That dress she puts on. It doesn’t fit. She’s gotten fat. She squeezes into it. She begins to behave as she did when it did fit. When she fit in. When she belonged. Amanda needs a play to live, to stay, to be needed. She’s auditioning for the Gentleman Caller as much as her daughter is. Love me. See me for what I once was. I wasn’t always this old lady in a dark, tattered apartment.

“Geraldine Page did something that was very like Laurette Taylor in that play I told you about: Midsummer. So much was going on and it was all in Geraldine’s face. Her eyes. Coming home exhausted with that oily bag of food. The food was supposed to be for her—or I thought it was. It appeared that Gerry wanted to sit down after working and just have something to eat, so she could sleep a bit and go back to her grinding work. But the children saw the bag and descended upon it. They were hungry, too. And I could see in Gerry’s face the resentment at having her food taken away, and then the joy in her children being happy, and then the sadness and the rage at the poverty in which they were trapped, and then the elation of them all being together and being sated, in different ways. This happened in less than a minute, and it was exhilarating.

“Some people have said that Laurette Taylor appeared to be a bag lady or a sad woman who somehow snuck into the theatre and wandered on the stage. She did. There was no artifice to her. There was no presentational style. She just appeared and was that woman. Even she was ‘acting’—on the phone, for the Gentleman Caller—it had that uncomfortable quality you sense when people are trying too hard, when people are pushing it.

“To be this sort of actress requires enormous vulnerability. You have to really expose yourself, give yourself, and this is not easy. I mean emotionally as well as within the theatre. That is one reason why we so rarely see performances that attempt this reality. The other, of course, is that there simply aren’t plays as good as Tennessee’s any longer. That’s that. I hope it reverses, but here we are.”—Marian Seldes, 2004

JULIE HARRIS

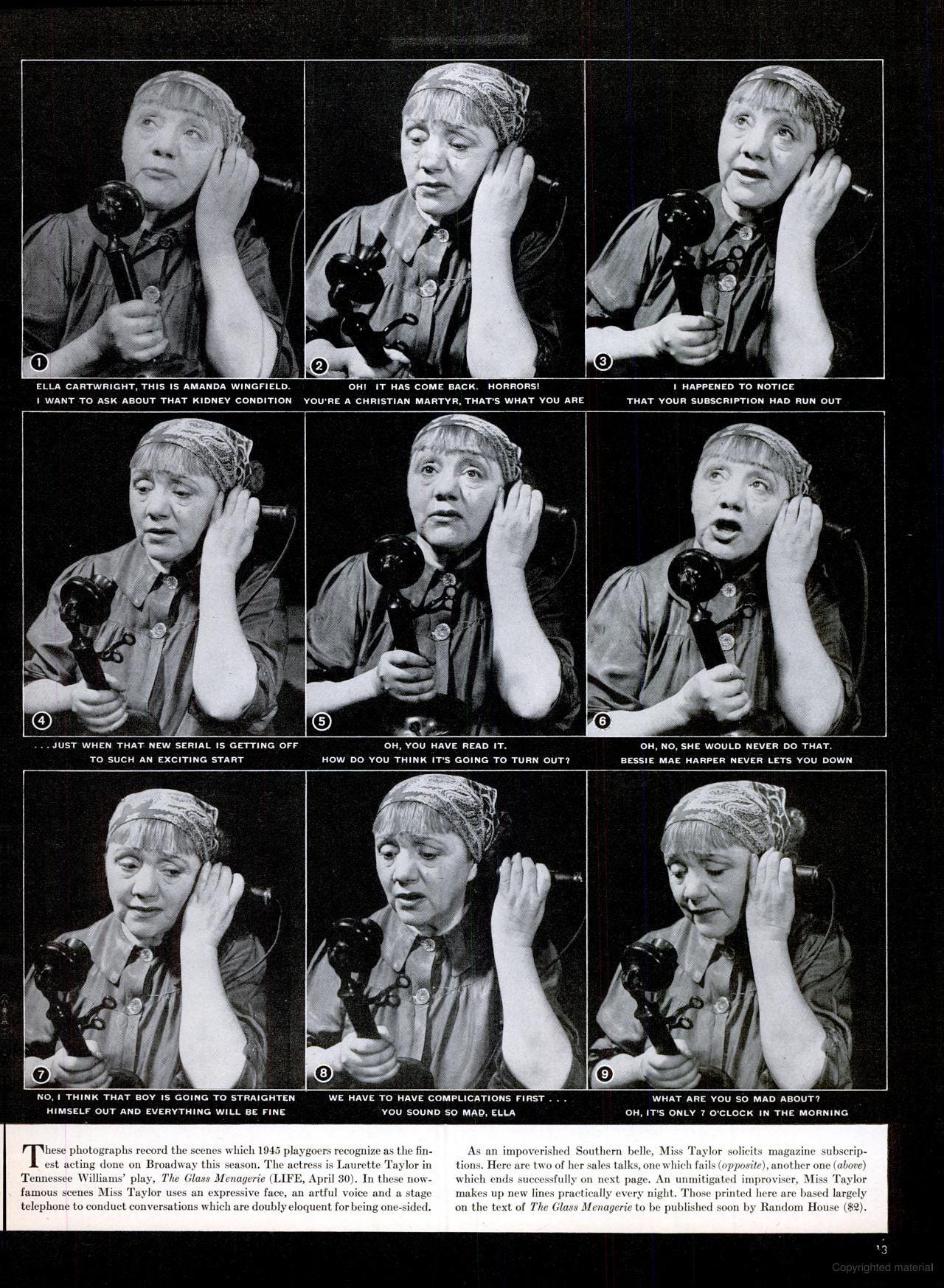

“Life magazine printed photographs of Laurette acting in the play [The Glass Menagerie], and I almost wore that issue out. A friend made a flip book out of the images, and as the pages went by, you could see her as if in real time. I loved that little book. I wish I knew where it was. It was a way for me to re-live that performance.

“The best photographs of stage work are the ones that catch us in the act of acting. Even if we act a scene exclusively for a photographer, that’s real, but if we’re asked to ‘pretend’ and strike the poses of a scene, it’s not real. It looks artificial, and I think—even if I have seen the performance—that it looks bad. I wonder if people would want to see that play given that artificial appearance of acting.

“Laurette lived her character in real time. I think a lot of people will tell you that that is what acting should be. Yes, it should be, but rarely is. It’s not easy to do. We’re not all as good as Laurette Taylor. We fake things. I don’t think Laurette faked a single thing on the stage as Amanda, but I know she faked a lot to get on that stage and play Amanda. She was not well. She was overweight and tired. However, every night, every time, she transformed herself into Amanda Wingfield, and lived the part as if for the first time. That’s another illusion of acting that is so hard. I never once saw Laurette anticipating an emotion, an action, a line. I saw the play several times, and I read it, and I was anticipating the emotions and the actions, but every time—every time—it hit her like a thunderbolt. She anticipated less than I did. I was a bit of a fan of hers, that play. I was very young. Just starting out. I thought that was a goal of acting, and it is, it was. I was too young to realize how high a goal that was.

“When I was Frankie [in Carson McCullers’ The Member of the Wedding], I thought of Laurette Taylor a lot. I was twice the age of Frankie. I was from a comfortable home in Grosse Pointe. I knew nothing about the South. I dived into the character. I read about the weather. The food. I inundated Carson with questions. Then Harold Clurman told me I was anticipating my Frankie too much. I could never be the Frankie of Carson McCullers’ imagination. I had to be the Frankie of my imagination. Because of Harold I realized that I didn’t have to spend a summer on a porch in the South to understand humidity, to feel it, to fight it. I didn’t have to spend hours with a young boy and a Black woman. There was thinking then—and I was right in there—that acting had to have at its core the real thing, the researched thing. No, Harold said: Imagine it. Sift it through your experience. And of course Harold and I spoke of Laurette Taylor. I think now that Laurette made her Amanda so real because it was hers. What am I trying to say? Laurette was truthful to what Tennessee wrote, but Tennessee’s Amanda had to wend her way through all these layers that belonged only to Laurette, and that Amanda picked up pieces of Laurette, making a tapestry that was utterly real.

“Harold used to talk about the great effort to become a character, and if we do our work, our due diligence, it then looks like we’re just coasting. No good actor ever coasts. It’s hard work. But it is much easier, and truer, if we have anchored our work in our imaginations, which is the bed in which we plant the words of the playwright. My imagination has often failed me. I don’t think I’ve been good in certain parts because I’ve failed to fully realize the character. That’s on me. A part just didn’t land in the right place in my imagination and my heart. So I worked hard, and I think the work was what people saw. That’s a debased sort of acting, in my opinion. All effort, little effect. I don’t think the great architects want us to look at their cathedral and marvel at how many miles the iron and the glass traveled, or how many people fell to their deaths constructing the spire. I think they want us to marvel at the building, the art, to imagine that we’re closer to God because of the way the light reflects in the stained glass. Effect not effort. And that is what Laurette Taylor epitomized. Effect.”—Julie Harris, 1991