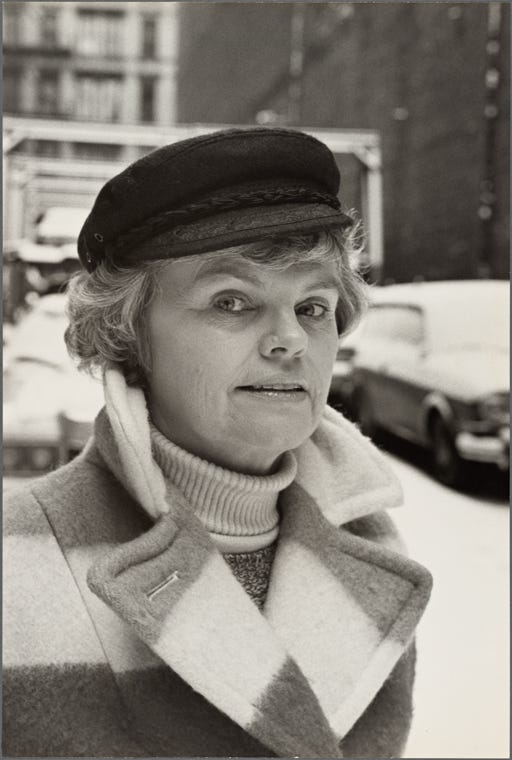

Madeleine Sherwood/Jane Fonda: Blank and Needy

"I cannot say—I don’t dare say—that I helped her or healed her. I can say that she healed me, this damaged woman."

Madeleine Sherwood vibrated with curiosity and honesty. Boredom terrified her, as did dishonesty. I could, she told me, ask her anything, but there were prices to be paid: If the question was stupid or cruel, I could expect what I deserved. However, she would respond.

I first met Sherwood at her apartment at 32 Leroy Street in the Village. “I tried to kill myself here once,” she told me, very early in our meeting. “I’ve been through a lot. I don’t waste time.”

Sherwood spoke at length about her life and her work. When we first met, the nation was glued to the Clarence Thomas hearings, and people were deciding—loudly and publicly—how they felt about Anita Hill, her appearance, her testimony. “I was married to a Black man,” Sherwood told me. “I know about those tensions, that hatred. I hear the things said about Thomas and his white wife. I hear the condemnations of Anita Hill, and these scars I have, they’re rising up again. I think they might have healed, or I might have covered them up, but they’re back. This is how Black people are, I hear, and this is what Black men who marry white women are like. I do not respect Clarence Thomas at all, but I know what’s going on there. It’s painful.”

I would eventually become friends with Patricia Bosworth, who had studied acting with Sherwood at the Actors’ Studio, and who later became an author of biographies of Montgomery Clift and Diane Arbus. When I met Sherwood, she let me know that Bosworth had contacted her about a book she was considering on Jane Fonda. Bosworth worked on this book for years. At some point in the early 2000s, Bosworth would travel to Sherwood’s home in Canada, where clowns gamboled on the lawn and through the rooms. (Sherwood was training and housing them.)

Sherwood, who had already asked me when I lost my virginity (“You remind me of James Earl Jones, who was a virgin until he was thirty, and then he made up for lost time. Are you making up for lost time?”), if I had a therapist (Sherwood would refer me to Dr. June Jackson Christmas), now asked me I knew Jane Fonda. I did not. Sherwood then said she wanted to talk about her.

Here is what she said, in 1991.

I feel protective of Jane, and I wondered what you were going to write about her. [Not much, as it turned out. While Tennessee Williams admired Fonda, they did not spend enough time together, personally or professionally, for me to pursue an interview with her.] I like what you’ve shown me, and I don’t think you’re vicious. I don’t think you have an agenda, but things happen to writers when they deal with Jane. Agendas appear. Someone always decides to attack her. It gets attention. It angers me.

I have taught for a long time. I get to know a lot about a student in the course of teaching them, talking to them, listening to them, figuring out what they want to do, can do, will do. Jane and I both studied with Lee [Strasberg], and we both were deep into that study. Studying with Lee transformed my life, and I don’t know this, but I think it transformed Jane’s.

You have Tennessee talking about religion and the masks it can provide. The masks it can remove. The protection. I fully believe that. I studied to become a therapist because I so needed one. A good one. I believe in therapy, but I thought I would take it farther and become a therapist, and so much of what I learned in that study, I had learned with Lee at the Studio. It was about becoming aware of all things. It was about a sensitivity to things that didn’t weaken me, or expose me unnecessarily to the actions of others, but just had me aware. A constant education. A constant study of the world around you. We function best, I think, in a world we know and understand. Well, I did that with Lee. Lee got me to reading everything about the theatre. If I did a scene from a play by Racine [Jean Racine, French playwright], well, Lee told me to read all of Racine, and he would share with me a biography or a study of his work. Lee did this with almost every playwright I worked with and on at the Studio, and I went there blank and needy. I was prone to severe depression. I was suicidal. I had been told I should report to an institution, from which, I was sure, I would never escape. So I ran away. I left Canada, where I’m from, and I came here to New York, and I had this dream. This damaged, eager, blank young woman came to the city—and then to the Studio—and asked to be educated, formed, filled. The Studio was a saving grace to me.

It was a sort of therapy, a sort of church. The Studio building, you know, was a church. I always found that appropriate. I found it like a church for me, because, if there is a religion, a God, a sacred study, I think it centers on people, on others. I think we are bound, and I think that the theatre can bind us together. I don’t know that Lee had a strong spiritual side, but he tolerated mine, and he believed, strongly, that the theatre was a means of binding us together, teaching us, elevating us.

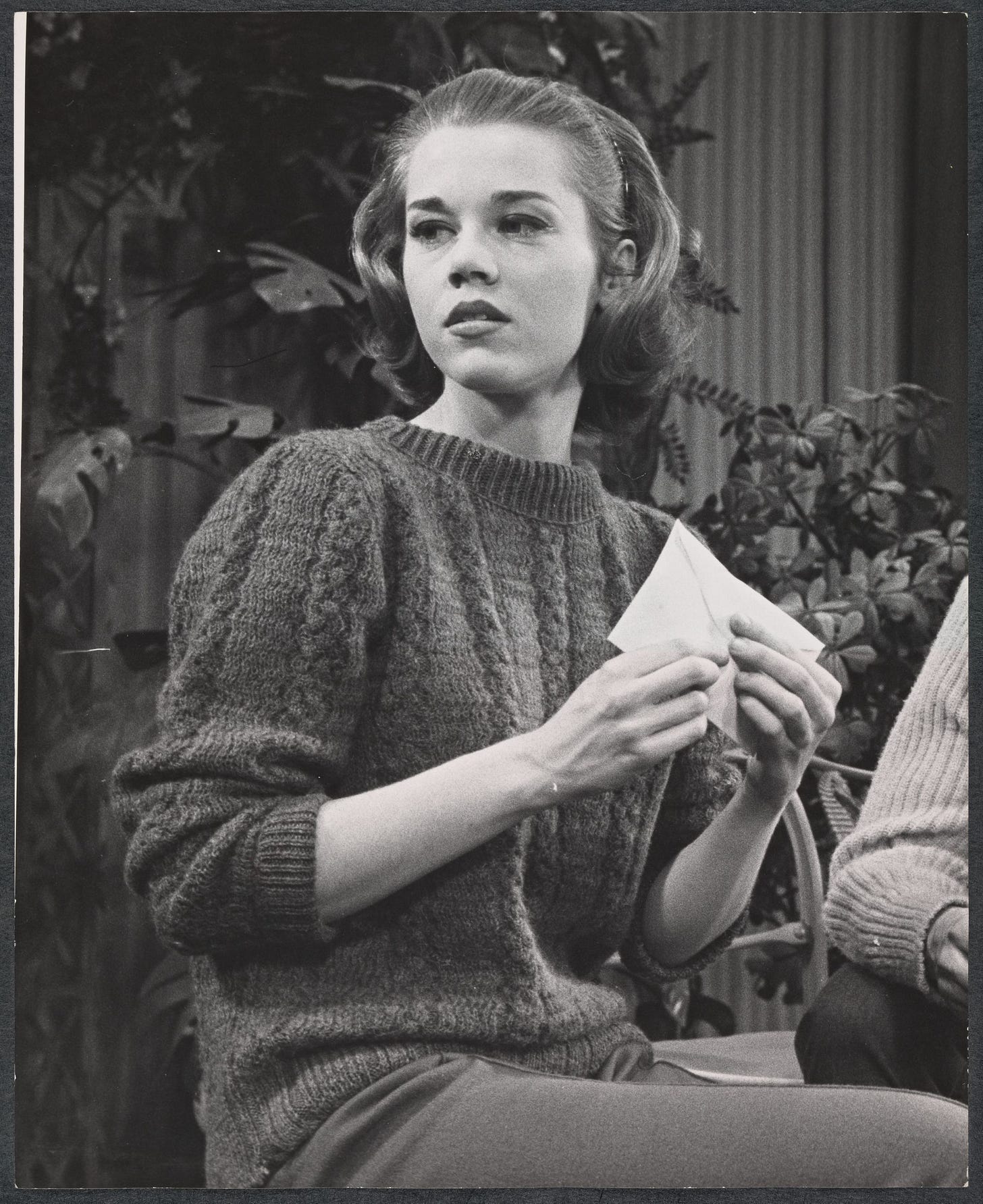

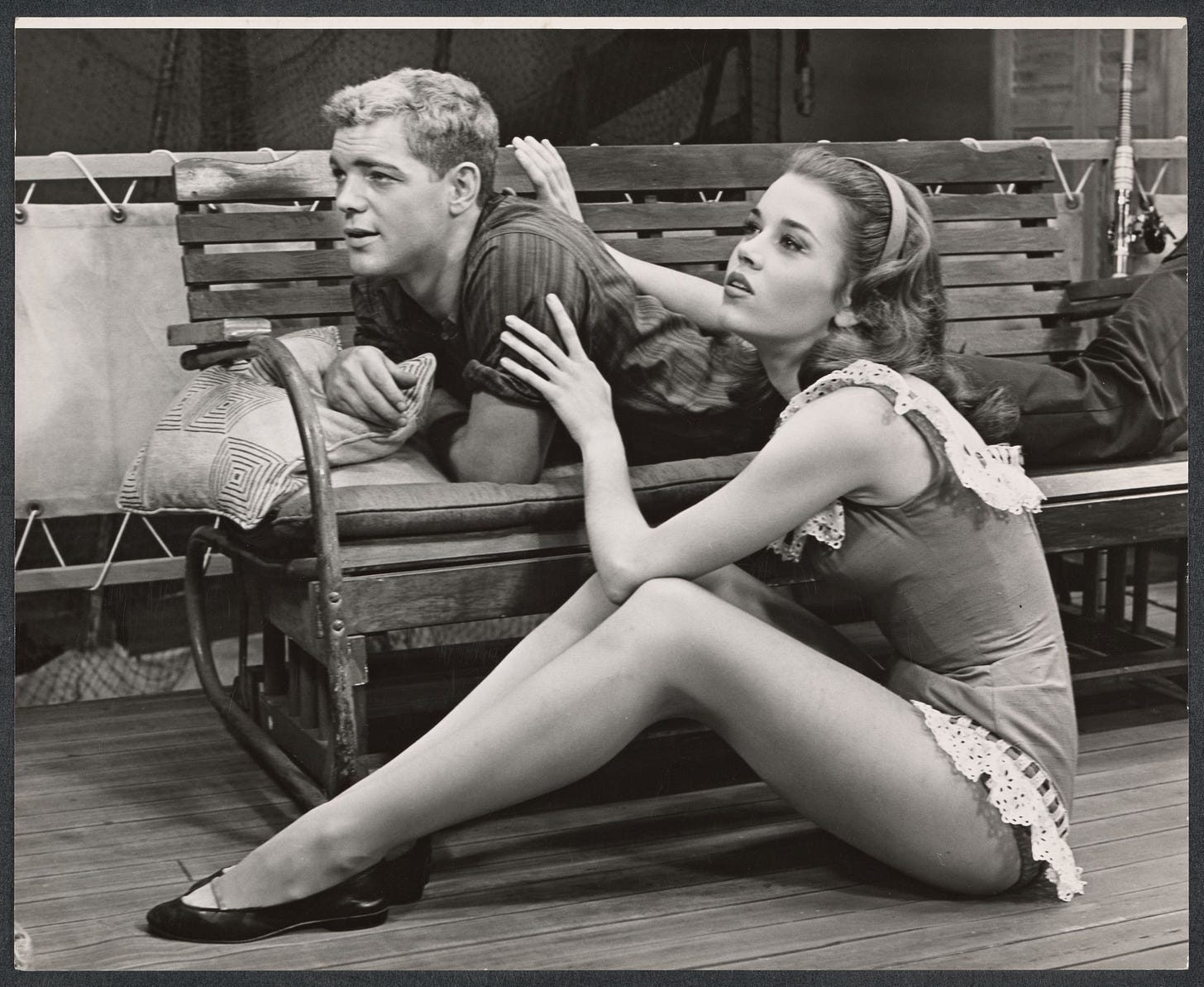

So now Jane comes into the Studio: Beautiful, open, needy. I was never beautiful, so my initial feelings toward her were not pleasant. I did not like her. I think I sniped about her a few times. I was so envious of what I assumed was her easy life, her smooth path. I didn’t know until a bit later that she was as vulnerable as I was. Frightened. Abandoned. I think so much affection has been withheld from Jane. She has since had carnal affection, fame, but a real connection with others is rare for her. I think. I stress that this is what I think, what I feel. But that mother rushed off to doctors and medications and psychiatrists, and then yanked from her children by suicide—that’s a lot to deal with. Dishonesty. Not being told how your mother died, and learning it through the gossip of others. I have trust issues, and I think Jane did as well. I think Jane has worked very well toward learning to trust. I think she’s better at it than I am. You see, I’m sitting here, now, and wondering how you might betray me.

I felt I needed to adopt Jane, and so I did. I didn’t announce that I was doing such a thing. I was just available. I became for her the friend I had needed and wanted when I was so young and new and damaged. Lee saved me, yes, but Lee was saving and teaching so many people. Lee couldn’t rush to my apartment and read with me and cook with me and tell me I was going to be fine; I was going to grow into an actress. I could do that with Jane. I could do that with others at the Studio. Kim Stanley could do that with Vivian Nathan. So many friendships were formed in our studies. Trust. We were repairing ourselves. We were repairing our talents. We were repairing the theatre and the world. I love that Maureen—a friend to so many—said to me once, You’re a fucking missionary, you are. Well, maybe I was. Maybe I am.

Here’s what I want to say. Maybe you’ll write about Jane one day. I want to stress that she is so committed to the world, to her friends. Jane was such a devoted student. She shamed me many times, and I’m a missionary! I thought I was dogged, determined, rapacious. That’s what Lee called me. Rapacious. Well, Jane was my match. My better, quite truthfully.

Look how she’s grown. What I felt toward her—this pretty, pampered, lucky doll—so many felt as well. A lot of people failed to take her seriously, and she is now one of our finest actresses. She stuns me.

I’m a funny-looking woman. I have been compared to a Pekingese more times than I want to admit. It was easy for me hate Jane for her beauty, but I came to love her for her kindness, her devotion. I want her to teach. I want her in a classroom or a studio, sharing her own journey, and helping others on theirs. But she does this through her work, through her activism. I think Jane and I both feel the need, the requirement, to earn our space on the planet, on the stage, on the film.

I cannot say—I don’t dare say—that I helped her or healed her. I can say that she healed me, this damaged woman.