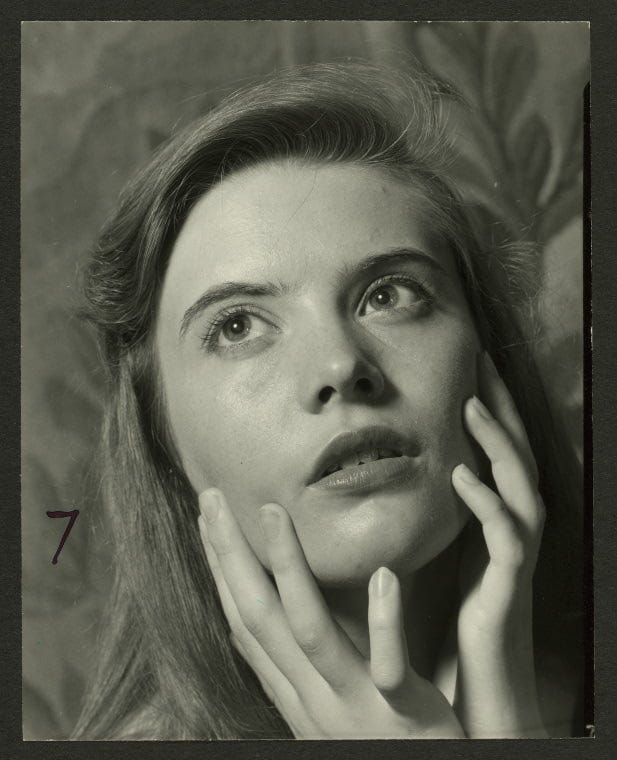

Lois Smith: No Resentments

"But there—here—is Lois Smith, pure and without a single resentment, as far as I can tell.”--Arthur Penn

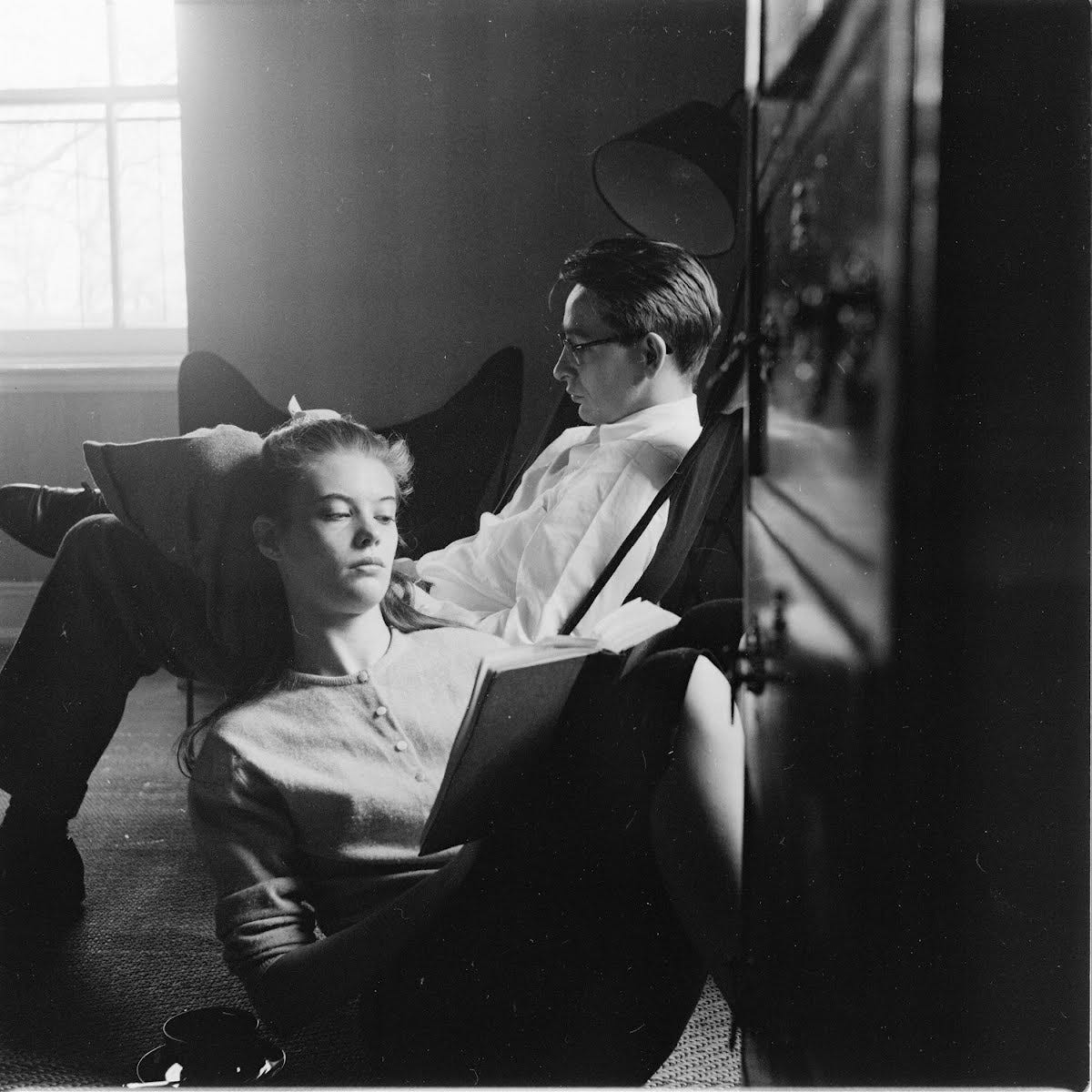

September 18, 2006: Lois Smith and I meet at the Circle in the Square Theatre for the memorial service for actress Maureen Stapleton, who had died the previous March at the age of eighty. Lois and I sat with Maria Tucci and director Arthur Penn, whom I had not met, but who was frequently leaning close to Lois and speaking to her. I saw Lois frequently laugh, and then I saw her patting Penn on the arm in a comforting manner. “C’mon,” she said, “that was a long time ago.”

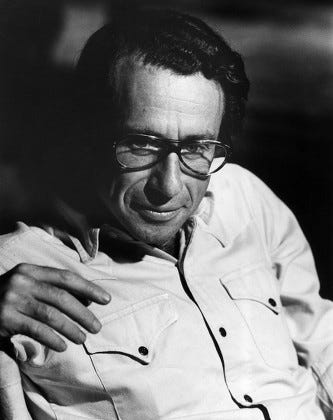

At the conclusion of the service, Lois introduced me to Arthur Penn and told him about the work I was doing on what would become “Follies of God.” Penn became animated and said “We need to talk. I’ve got stories about Tennessee Williams, and lots of other things. Tennessee really liked and often needed my wife.” (Penn’s wife, Peggy Maurer, was an actress who later became a dedicated therapist, specializing in trauma.) “Tennessee,” Penn told me, “would rely on her. Not as a patient,” he continued, “but just whenever he saw her, or whenever he could remember how to reach her.” Tennessee had once convinced a telephone operator to connect him to Peggy Penn by telling her that he was in turmoil, she was a “savior,” and she was on West 67th Street. “Or 66th,” Tenn added. “I can’t recall.” The operator was able to connect him to the bemused and sleeping Penns.

I met with Arthur Penn a few weeks later, and we walked into Central Park, near the Tavern on the Green, until we found a bench. Before I could show him any chapters I had written or share any notes I had taken of other subjects, he wanted to tell me about Lois Smith.

Arthur Penn wanted to cast Lois Smith as Lily Berniers in Lillian Hellman’s Toys in the Attic, and he remembered her readings as “remarkable, frightening.” Penn was in what he called a “magical” part of his life: He had enjoyed a success with William Gibson’s Two for the Seesaw, and then had won a Tony Award for Gibson’s The Miracle Worker. Both of Gibson’s plays had featured Anne Bancroft, who had died the previous year, and who continued to weigh heavily on Penn’s mind. “Lois had some of the same energy as Annie,” Penn told me. “Annie was more volatile; Lois more poetic. What did [Harold] Clurman say about Lois?” I stopped Penn and said that Clurman had described Lois as a “lyric,” and Penn heartily endorsed this description, but said, “A wild lyric. A tough weed at the end of which is a beautiful blossom.” (When I later told Lois about this, she made a face and said “A tough weed?”)

Lillian Hellman was a tough negotiator, Penn remembered. “She was dead-set on Maureen [Stapleton], which I endorsed,” he said, “and she wanted what she called a top-of-the-line cast. I was a journeyman to Kermit [Bloomgarden, the play’s powerful producer], and Lillian was God.” Hellmann got the cast she wanted—Stapleton, Irene Worth, Anne Revere, Jason Robards—the scenic designer Howard Bay, and even a piece of music by Marc Blitzstein. “I wanted Lois,” Penn remembered, “and Lillian was fine with that, although she remembered two other actresses who were, to her eyes, equally fine, but she told me to do as I wish. But,” Penn laughed, “Bloomgarden shook his head and proclaimed himself done with our demands. He stated that he had stood aside and let us cast and hire and piddle, and we had chosen most of the jury we wanted and needed—he used that term—but he was making a peremptory move, and he wanted Rochelle Oliver. I had already told Lois that I wanted her, that she was going to be Lily, but Kermit made his decision. I was overruled.”

Penn quickly added that Rochelle Oliver was—and remains—a marvelous actress, and she had a deserved success in Toys in the Attic. However, Penn never forgot his deep guilt at having to notify Lois Smith that he could not honor his word, his offer, to her. The close, fitful, affectionate conversations I had witnessed at the Stapleton memorial had dealt with this “betrayal,” as he put it.

“But Lois,” Penn told me, “doesn’t have an angry bone in her body. It amazes me. Lois enjoyed—enjoyed—the success Rochelle had in the play. Lois later enjoyed that Shirley Knight was chosen to play Irina in The Three Sisters, when I know Lee [Strasberg] offered her the role, and didn’t even bother to let her know he had changed his mind. Lois heard about it from a reporter. And never a negative thought. Write a book about her! Do you know how rare this is? Do you know that virtually every call Tennessee made to my wife in the middle of the night or the middle of a crisis was about anger? About resentment? Why wasn’t he a great playwright? Of course he was, but he worried if he didn’t make a list. Why didn’t I direct Night of the Iguana? I was otherwise engaged, but Tennessee felt it was a slight, a judgment. How could Peggy—how could anyone—convince him that the world is inexplicable? There are just so many things that interfere in our lives, our choices? But there—here—is Lois Smith, pure and without a single resentment, as far as I can tell.”

When I took this conversation to Lois Smith, she was, as always, kind and cool. “I remember that Arthur sent me a beautiful bouquet of flowers and a sweet note,” Lois said. “He didn’t have to do that. It was lovely of him to do so, but I never expected too heavily. I have been lucky, but I never thought I should or would get something. We all have our moments, and I stress that these are our moments. I consider myself a part of the theatre, the acting community, so I want there to be success for everyone. I wanted that part; I would have loved playing that part. But, you know, a lovely and gifted actress got the part and I was grateful to see her do it. I was happy for her opportunity. It is the only way to live—for me.”

I spoke to Lois on July 24, 2023, when we are being told that the theatre is in crisis. The theatre may collapse. The theatre will certainly not be the same.

Lois will have nothing to do with the dire predictions.

“I’ve been around for a long time,” she told me. “I’ve heard every prediction. I’ve seen and lived through every challenge. The theatre is a part of our world, our lives. As to resentment: I don’t have resentments. I never felt anything that was mine—or might be mine—was taken from me. We are all working and hoping, and I have been so lucky in having things work out. Things have worked out for so many of us, and they still will. I believe that. It’s a frightening time. Things will shift and alter, but we’ll go on. No resentments. Hope and courage and care. And I keep going to the theatre, and I see things I like, that I love. The work is there; the talent is there. Now, we have to be there.”