Kim Stanley on Marilyn Monroe

"I wish more of us had had the courage to help her forget about the night visits and the jabbing. To walk her to safer places. Safe among friends.”

On a quiet summer afternoon in 1992, not long after riots that had shaken and burned the city, Kim Stanley welcomed me into her bungalow apartment. After several hours of conversation, I asked her about Marilyn Monroe.

Stanley inhaled deeply, looked at me sharply, then softened. “I’ll answer that question,” she said, “because I don’t think you’re prurient. I think—I hope—that you want a serious discussion about her.” I told her I did.

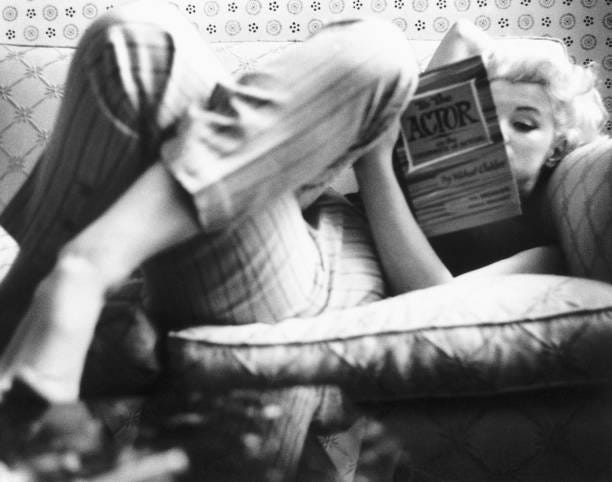

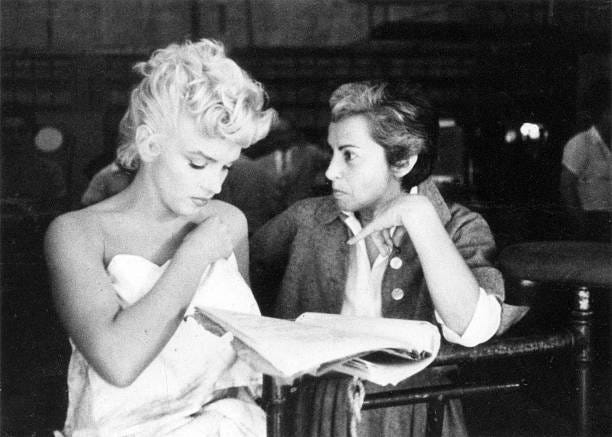

“What I remember,” Stanley continued, “is the perpetual student that she was. I spent a lot of years studying religions, modes of thought, prayer. I was in turmoil, and I hoped I could find some aid, some comfort. What I remember is my hunger for that knowledge, for that comfort. I pursued religion the way I had once pursued alcohol or that one pill that would calm me down or get me going again. I became insufferable, and I had read so much at one point about Catholicism that I knew more than cradle Catholics, who had just been believing blindly since birth. They had not studied—or needed to—as doggedly as I had. I went deep, for the minutiae. Then I would move on to Martin Buber, then on to Buddhism. I was ravenous. This is my memory of Marilyn. She was desperate to learn, to improve herself, but she was not in competition with anyone but herself. She called herself a blank slate, an empty vessel, and her job was to find things to fill her up.

"I loved her innocence and her native intelligence," Stanley said. “She would start off knowing little or nothing about something—a writer, a play, a country—and then we’d lose her for a while, and she’d come back, full of joy at what she’d learned. Some people learn things to show off, but Marilyn wanted to bring the joy she had discovered to others. She wanted you to join in. We bring who and what we are to anything we learn, and what she brought was pure openness, so when she would tell me what she had discovered in reading Pirandello, it was utterly unique and, of course, correct. It was through her, it derived from her understanding, and she had no bias. None. She taught me that there was no right way to get a play or a book or a person. It was what you felt at the time you discovered it. Her mind was open in the best possible way. I clutter things up. I bring too much to the study, to the rehearsal, to the performance. Marilyn may have done that when she was working on a film, but when I saw her studying and rehearsing, I saw no clutter. A straight, clear line.”

Why are we so obsessed with Marilyn Monroe? I asked Kim Stanley.

“Well,” she laughed, “why are you obsessed with Marilyn Monroe? You brought her up! I think we would have parted ways, and I would never have thought to bring her up. Not because I don’t care about her. Not because I don’t want to honor her. I want to leave her alone. Let the work inspire. Let the memories be private with me and those who knew and loved her.

“But,” she continued, “I’m going to hazard a guess. I think we see Marilyn from and on several levels. There is the gorgeous woman. So many gay men have compared her to angel-food cakes and towers of cream and melting ice cream. Norman Mailer had a few orgasms on her grave when he wrote about her. She was SEX, he proclaimed, and, remember, gas-station guys with pimples and hard-ons pumped for her. Oh, that was some confession, Mr. Mailer! Marilyn represented sex and glamour and, also, sweetness. That memory you shared with me from Barbara Baxley—about how Marilyn greeted fans with so much sweetness, and it was a sweetness that tempered the sexuality until she was almost virginal. I think men—straight men—wanted to fuck her, and women and gay men wanted to protect her. There is a myth now that If only I had been there, I could have saved her. Well, no one could save Marilyn but Marilyn, but no one tried. That I believe. No one tried.

“Another level of Marilyn,” Stanley said, “is the tragic one. There was a lot of meanness, cattiness, toward Marilyn. She could make you doubt herself, I tell you. People envied her beauty and her power. She was belittled. Then she died, and she was the sad little girl abandoned outside, left for the wolves. So now we sanctify her, and some erase her faults and her fears, and act as if a blessed idol was defaced in our presence, under our watch. Well, I despise that. I don’t like guilty money thrown, like a cover, over past neglects. Don’t light candles for a dead woman. Instead, choose to be more compassionate about the women who live among you now.”

Stanley paused a bit and then asked me if I had seen the 1958 film The Goddess, in which she starred as Rita Shaw, a character many believed to have been based on Marilyn Monroe. The script was by Paddy Chayefsky, and Stanley stated that he denied it was only about Monroe. “Marilyn was the big star at the time,” Stanley said, “and there were certain similarities, but Paddy was, as always, after something bigger. Rita—who was once poor little Emily [Ann] could have been any number of girls who were prodded and molded and extruded into movie commodities, symbols to sell movies or toothpaste or face powder or shampoo. The director [John Cromwell] kept reminding me and the other actors that there was a human being, a soul, a heart inside this woman, and everyone was expressly told to ignore that. Instead, demands and demands and demands were made on her, and I began to feel that I would have to rip open my chest to show that I did have a heart. Be pretty. Behave. Show up. Do what you’re told. Make love to me. Give me money. Make me feel manly. And I was just screaming to be seen, to be held, to be appreciated. I know that feeling. I have been that crazy. I have been that ignored.”

Stanley went on to say that Rita Shaw was a bit of Marilyn, and a bit of Carole Landis, and a bit of Mary Miles Minter, of Kim Novak, of Jayne Mansfield. The sad upbringing displayed in The Goddess can be traced to a number of “goddesses,” and in Hollywood parlance it was part of a glorious arc: Sad, poor little nothing is touched by stardust and lives happily ever after, and we the public can witness this transformation and be changed as well. Buy the ticket, buy the toothpaste, buy the magazine, use the Lux soap that keeps her so beautiful.

“You see,” Stanley told me, “beauty can be God-given, but the type of beauty you need to illuminate a movie screen requires maintenance, hard work, agency. That’s why you need the soaps and the makeups and the powders and the diets. The constant keeping of the car [the body] in the shop, tinkering, remodeling, getting the dings out. That I took from Marilyn. I saw what she put herself through. I had never heard of such expensive things as Erno Laszlo until I met Marilyn. Thirty lashes! You filled a sink with the hottest water, and you threw the hot water up and onto your face at least thirty times. Cleanliness leads to beauty, and the expensive soap and the expensive cream will keep you beautiful. Marilyn’s life was a series of regimens—of beauty and diet and sessions with Lee [Strasberg] and and Paula [Strasberg] and Natasha [Lytess[ and her shrinks. I saw the itineraries. And she would crack. She would rebel. Who wouldn’t? She needed to be free. I talked to Maureen about you, and she told me that she told you that what Marilyn wanted was grass beneath her feet and a door she could close. She had never had those. Ever.

“So the pretty girl would crack up, and she would stop doing the thirty lashes and patting on the hundred-dollar creams, and she would retreat into books and plays, and she would reach out to people like me and Maureen and Vivian Nathan and talk about ideas. She was wonderfully intelligent and creative. She got characters better than most because she did not have the facade of pretension that education gives to some of us. She was never defensive about anyone. She never condemned a character as evil, but she wanted to know how that character got that way.

“I used a lot of Marilyn to play Rita Shaw, because I knew her. We were never close. I do not want to imply that. But I spent time with her. I saw her work. I liked her and I cared for her. Marilyn and I both knew abuse when we were young. We were sexually violated. We were, as I’ve told you, visited in the night, presumably safe among friends and family, and violated. When Marilyn was doing a scene—was working on a scene—for the Studio, she was working with Lee, and she was unable to stop being the strong commodity. She had been taught so well to be MARILYN, always performing, always ready, that she could not allow vulnerability or fear to show in her face or her voice. Lee told her she needed a fissure to reveal itself, and for pain to creep through that fissure. Marilyn was running out of the Studio one day and she said she was going home to work on fissures. Marilyn finally got the vulnerability and the fear, and Lee, crying as he told me, said that she could feel the violation and the fear by remembering the feeling of fingers jabbing inside of her from a man she had been told to call Daddy. The state had placed her in a home, given the man a check, and now she was his, and he would visit her and have his way with her, and she could think of the smell of cigarettes and she could remember the jabbing of the fingers, and she could remember that she would not cry, she would not whimper, because then where would she go? Where would they take her? You grit your teeth and you take the jabbing. Perhaps it is what you deserve, what you were meant for. Well, I took that to Rita Shaw, and I imagined jabbing fingers, and I did think of Marilyn.

“Marilyn’s rescue was ideas. It’s easy now to say all sorts of things about her, but I remember how valiant she was. Look at what she accomplished over such odds. Look at what she tried to do, when so many of us have given up. Marilyn had courage, and I wish more of us had had the courage to help her forget about the night visits and the jabbing. To walk her to safer places. Safe among friends.”