Joan Didion: Language is Morality

"Language is morality. It is the architecture of one’s morality—the very structure upon which your morals—your character—can or cannot rest."

Joan Didion would sometimes move out of the restaurant of the Carlyle Hotel and sit in the Gallery, alone, quiet, nursing a pot of tea. Didion would have left her husband John Gregory Dunne and another friend because she was anxious to think, to get away from an argument.

Because my fellow workers at the Carlyle knew I often spoke to Didion and was more than a bit enamored of her, they would alert me to the fact that she was in the Gallery. I will always be grateful to Paul Goldenberg, who was best at letting me leave my position at the front desk to go see her.

I would always ask Didion if she wanted to remain alone, but she was always polite. Didion also wanted an audience. She wanted someone to know why she had left a table in an elegant restaurant to sit at a corner table with a pot of tea.

Here is something she said during one of those moments that I think about frequently:

Language is morality. It is the architecture of one’s morality—the very structure upon which your morals—your character—can or cannot rest.

Was Didion leaving a discussion that she found amoral? Immoral? She did not say, but she remembered that I had once asked her why there were references in articles and interviews to the re-reading, underlining, study, and discussion of the work of other writers. I remember a description of John Gregory Dunne standing in their pool with a copy of William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice, reading over and over a particular portion of the book and calling out to Didion at poolside to indicate that he could now see how a placement of words, an emphasis, an elision, an adjective was masterly. Didion spoke of re-reading Iris Murdoch and Joyce Carol Oates and Norman Mailer.

All writing is confessional, she told me. The writer reveals the story along with the person telling the story.

Joan Didion’s definition of morality in this context has to do with a writer revealing where he or she looked, and what he or she chose to see and to share. Didion was firm on this being a form of morality. “Where you choose to see things and how defines all of us,” she told me. However, language is not simply a string of words that appear on a page and relay information: Language is autobiography; it is a call to action; it is a confession; it is an exhortation; it is a strip tease in which the writer bares beliefs and prejudices. Didion said that she once told a student that even bad writing reveals more than a lack of focus or talent—it reveals a lack of character.

Language is also violent. Language can build or destroy a mind, a civilization. “Or a dinner,” Didion wryly commented, looking toward the Carlyle restaurant.

Carefully choose your words, she told me, because it is an examination not only of a character in fiction or of a book you’re reviewing: It is an examination of your character, your vision. Your morality.

Joan Didion didn’t understand how she felt about things until she was able to write about them. To sort it out. “People get things,” she said. “I mean, they buy things, and they require assembly. I’m not good at this. I get anxious about this. But I find the manual, and I take each item in the box or the kit, and I place them flat on a surface, and I look at it all. From above, from a height. I know what I’ve got to work with. Then I read the manual. Then I look again at the stuff on the table or the floor, and I can approach it. That is what I do with a fictional character or a book or a person I’m writing about. I sort out what I’ve got—what I can see, what I can use—and then I proceed to assembly.”

Always afraid that she might lose this ability—this way of seeing—Didion studied the writing of others to see how they maintained both their talent and their means of sharing the story.

“I’m close to a lot of women writers,” she told me. I asked if this might be because women share similarities in how they look at things, then share them. “It could be,” she said. “But I think women are braver. I think some rare form of freedom arrives for them when they can write. I’ve seen it in groups of women where they can speak for the first time about what has happened in their lives. They just hand it over to you.”

Didion briefly described a group to which she had been invited by Eleanor Perry, a screenwriter, who had become active in the Women’s Liberation movement, a cause to which she believed Didion had offered insufficient attention. “She said the toe I stuck into that pond had barely gotten wet,” Didion said. It was at this meeting, in the early 1970s, that Didion heard the testimonies of women who had endured physical abuse as their “duty,” who had given birth to unwanted children because that was their “job,” women who were told that unwanted advances and unrewarded employment were the “cost” of being a woman. “Women were told they were protected,” Didion said. “I was told this. But women are the least protected of us all. So when I read Joyce [Carol Oates] or Elizabeth Bishop or Iris Murdoch, to name just the ones we’ve talked about, I see a lack of fear. I see such openness. I see almost a sense of wonder that they can finally express these things. I see flags being waved that we are not—any of us—protected.”

Joan Didion once read something I had written. She told me that I got in the way of my own work. I still do. It’s something I need to work on always. “It’s fear,” she told me. “It’s not a lack of skill. You’re afraid that you’re not being clear, and you’re not being clear fast enough. You can’t rush a theory. Writing is a steady introduction of your way of seeing something and sharing it with someone who may or may not agree with you. Move steadily but softly.”

In Joan Didion’s apartment there were books whose spines were cracked. Pages were dog-eared, underlined. Didion was studying how it was done. Didion praised Joyce Carol Oates for how she stealthily led you to her characters, revealed plot points, beautifully, powerfully utilized language. “She makes words I know well pop as if I’ve seen them for the first time,” Didion said. “It’s the skill in placement.” Didion did not like the word “languorous,” because it implied laziness or sloth, but I think she meant seduction. “That’s it,” she said. “But that’s a word that is so often misunderstood.”

She paused.

“Except by women.”

»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»»

If our language reveals a morality—or a lack of one—we are in a dark age. Our language is debased hourly, daily, via text or social-media post, or by the increasingly vapid criticism we get from formerly respected magazines and newspapers.

Cruelty is impulsive, and the actions taken to express cruelty occur and then burn from the memory of the sender like a cheap wine or a quick hand job. The recipient feels it longer, and marvels that it was sent.

“Unsuccessful people are impotent,” Tennessee Williams said, in 1982, and he included himself in this estimation. Williams was writing—he always wrote—but it was not good, it did not reach his high standards, and he wrote and he re-wrote, punishing and slapping his flaccid talent until some blood rushed into it.

The impotent are now employed—either by self, via social media, or by a publication that slavers after involvement in this social media context. It is no longer important that a review prompt a reader to read more or to think: It is sufficient for the critic to be funny, cruel, to offer a line that can be shared to Twitter or Facebook and get some clicks and some traction. To attack is to attract. It does nothing for film or literature or anything, but it gets people talking, laughing, pointing.

So a playwright—alleged—posts constantly about his plays, his direction, his reputation, the sweet offers he gets, and I am emailed by a well-known director who asked “Where are this guy’s plays? Have you ever read one? Are they published?” They are not. There is also no reference through the most exhaustive search for a review of any of his plays or his direction of plays. He is a figment. He writes with the exhaustion of the seasoned professional, sharing things he has read, “As Beckett so beautifully expressed…” and he has an audience. A small audience, but as Didion told me, “The bad choices of a writer, if we choose to accept them, become ours.” So these figments hang together.

The opinions of theatre workers who have failed to be employed by any theatre or producer or playwright of merit, can be called upon to offer their opinions based on plays they have done in living rooms, or Shetler Studios, or some rented, dirty space. They form their own “theatre companies,” and now they opine on choices made by actors and directors who have achieved an education and an audience. To read a failed man, a self-appointed “expert” on Shakespeare delightedly ridicule Denzel Washington’s Macbeth by comparing it to his own production—done in a sweaty alcove with Kickstarter funds—would be laughable but that he has adherents, who believe that the best, the “purest,” theatre is that done by those who failed to gain admission, and to tiny audiences who share a similar fate and a similar dream. And yet…someone will share their opinions, because we live in a time where there is an open-admissions policy toward all language, all opinions. Everyone must be heard. These are people who don’t realize—or don’t care—that language is morality, that language has power, that language defines us.

The professionals are no better. They approach their tasks as if they were microphones, which they tap and ask, “Is this on?” and then go into a routine. These critics are not here to inform; they are here to impress. A perpetual audition. It is no mystery why the brains of our critics are so soft and silly: I spent an evening with a group of them—ephebes in bright shirts with the plain women who are their consorts—as they sang to karaoke and speculated on who might be cast in certain musicals in certain years on certain networks. Trivia night with the boys and girls who had no friends in high school, but who sat in tight bedrooms that smelled of Clearasil and smegma, piles of albums and CDs of musicals strewn about the room. Smart people devoted to dumb lives, resentful of those who made it to the stage or the page or the screen. Their performances occur through words, clicks, hits. All of them will disappear, their evanescence inevitable, but the effects of their immorality will linger.

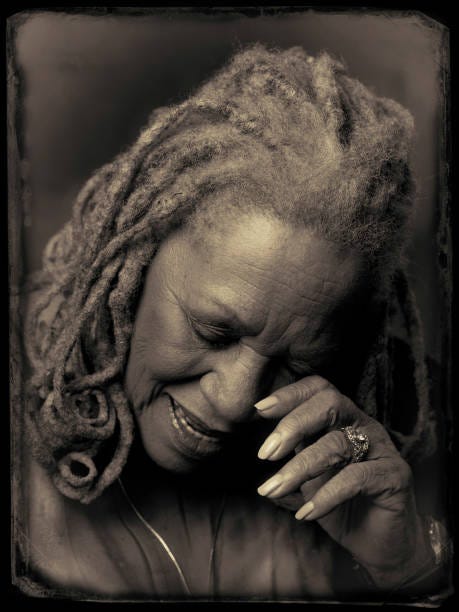

I wish I could have shared this quote from Toni Morrison with Didion:

“Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity-driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek—it must be rejected, altered and exposed. It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind. Sexist language, racist language, theistic language—all are typical of the policing languages of mastery, and cannot, do not permit new knowledge or encourage the mutual exchange of ideas.”

I recently bumped into an acquaintance at a party. She had reveled in a mean-spirited, impotent hatchet piece that had been written about me. She bubbled and hugged me, asked how I was. Then she asked why I had not reciprocated her hug. I told her I assumed she didn’t care much for me, my being a “ruined fraud” and all. She looked utterly puzzled. I showed her the screenshot of her statement. She was horrified. She thought she might have been hacked, then realized it was indeed her statement, from her Facebook account.

“I have no memory of this,” she confessed, crying. “I guess I got caught up in a moment. I do not remember this.”

I do not doubt her.

Language is morality.

James Grissom worked at the Hotel Carlyle in 1998 and 1999.