It’s not that I don’t like talking about acting: I actually love talking about acting, in the right place and with the right people. I don’t like talking about getting to the heart of a part I’ve played or am playing because I don’t know what I’m doing most of the time. I’m just trying and guessing and stumbling, and I hit a mark once in a while and it’s there, the part falls into place.

In a class we can all assume we’re stumbling, and we ask questions and we try things. I try to make class like a rehearsal. No one knows anything, really. They have ideas; they have instincts; they’re ready to try things out. And that’s enough.

I have never fully plumbed the depths of any part I’ve played. I don’t do percentages—I think that would be horrifying—but I know a great deal about my character on certain issues and in certain scenes, and other times I’m just doing my best and praying I don’t disappoint the playwright and the director and my fellow actors.

What I want to stress to you—and I think I need to, because you’ve mentioned other teachers and techniques—but there is no set of rules to act. There is no right way to act, and the absolute wrong way is to fail to be truthful. Truthful means to the play, to the character, to the human being you’re examining and presenting. If what you’re doing isn’t something you can attribute to a human being you’ve known or observed, then it’s not real, so it’s going to be bad acting.

I don’t like to say bad acting, unless I’m in my house or my class and talking with friends. Bad acting is acting that has no truth in it. It’s adjectives dancing; attitudes well lit and practiced. I hate it. And I’ve done it! Own up to your actions. I’ve been at my worst in television, I think, where it’s fast and you don’t have time to come to any understanding of the character, so you latch on to an adjective. Funny. Dark. Evil. Scowling

Lee [Strasberg] was great at getting me to relax, to just pull the nerves and the muscles in my body apart and be this mushy thing, a sponge. You can’t be rigid, and I’m prone to rigidity. I get scared; I tighten up. If my body is loosened, my mind follows, and I can be receptive in a way that isn’t always natural to me. When I’m receptive, I can learn from anyone or anything.

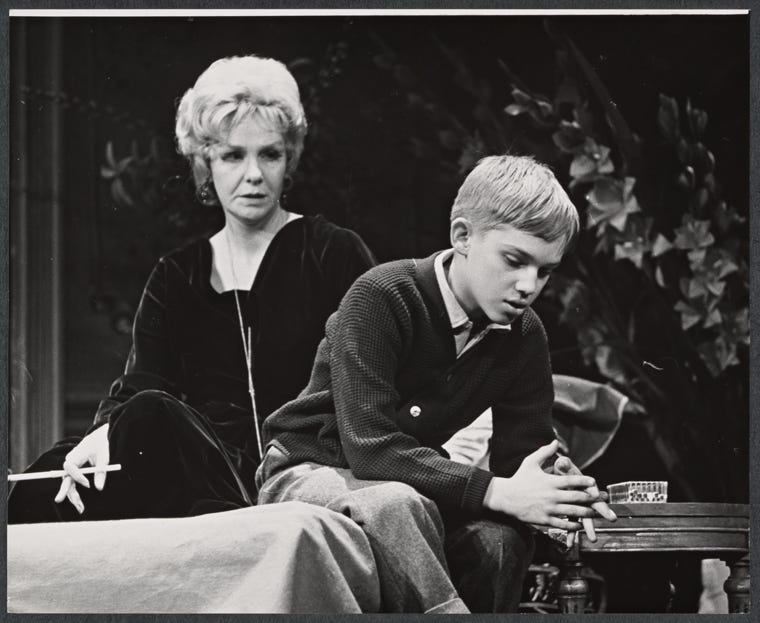

You respond truthfully and instantly to whatever happens on the stage. You have to. I remember being in a play with a little boy [Page is speaking of a very young Richard Thomas in the 1963 production of Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude], and he looked at me one night in such a pure and sweet way, as a little boy would, and it was not as we had rehearsed it, and I responded in that moment, as a woman, as a mother, as a very frightened, confused character. Everyone in that company could feel that something had changed, and they adapted. I think the play was better that night. We ran right toward some truth.

I also respond to mistakes. Props break; sets fall; an actor forgets lines or doesn’t show up. You don’t get angry: You respond in character, and the rotten actor is the one who gets rigid and thinks, When this has righted itself, I’ll get back in.

Just about every play I’ve been in has been improved by a mistake, either in staging or in my thinking. Before I was a mother, I would think an action was false or hokey. Thank goodness my director forced me to re-think that. I was wrong. It’s okay to be wrong, but you have to have the courage to be corrected. We never get this right. We keep trying. We pray that we get better.

I was accused of really bad acting in a play because the man who was opposite me [Darren McGavin in The Rainmaker] got bored and just showed up. He was handsome and looked great without a shirt, and that was enough, I think, for some in the audience, and certainly for him. But I was committed to Lizzie [her character], and I played her needs, her clumsy advances, her rejections. People were saying that the actor was a “natural,” so “clear,” and I was just too, too much. Even the director told me I might want to pull back, but I refused. I wasn’t going to neglect Lizzie: I was going to be true to her, not to the actor. That play would have been entirely subverted if both of us had “pulled back.” I don’t believe in desertion. I don’t do it.

When I took over from Margaret Leighton in Separate Tables, people I thought were colleagues actually laughed and told me that Leighton was pretty. How could I pull that off? I was not pretty, clearly. They could see me as the dowdy character, but not the elegant, sexually possessive character. Word filtered out that the play would hire another actress to play the pretty character, because I simply couldn’t do it. I got so angry, but I put it into the work. I was going to be truthful to the character, and, by God, I was going to be pretty. And I was.

I’m telling actors a lot to not forget that we played around at first when we dreamed of acting. We can’t let the play disappear. Part of making myself pretty—for a play or a party—is playing. Fix the hair; put on a wig, maybe; new lipstick; reshape the brows; push-up bra; torturous girdle. Who is that woman? It’s me, and it’s not me. It’s the character. It’s called acting. Truthful people live behind masks all the time. I have a mask, yes, but I’m truthful back there.

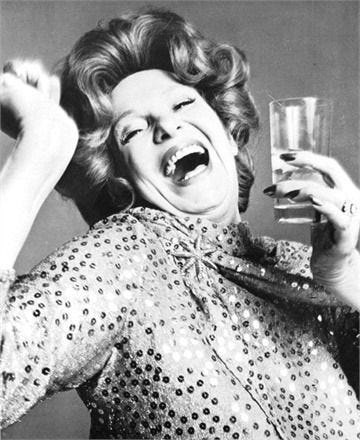

I did watch a lot of old movies to play Alexandra in Sweet Bird of Youth. I’m not a movie star, but I’ve been in love with so many of them. I know how they look and move and react. They weren’t always movie stars: They studied and worked. So did I. I created the heart and the mind of that woman first. It was all true. But then I put up a beautiful scaffolding that made her completely true to what Tennessee [Williams] had written. Phonies—all of them—are utterly true. Real. Phonies may be the most truthful of us all—they’re so committed to a script they want so badly to be true.

I was at a party years ago, and a woman came in and started talking, and I had to fight the urge to laugh. She was funny. She wasn’t trying to be funny—which is tiresome and almost never funny—she just had a way of speaking and moving, and it made everything funny. One of the first questions she asked, to no one in particular, was “Did any of you see David Susskind’s Open End the other night?” She adjusted her hair, took a sip of her martini, and launched into a recap of the program, which was about our crumbling society: the Vietnam War; poverty; racism; rioting. “Listen,” she said at one point, and her head moved so strongly that a pendant earring fell into her blouse, “I’m not ready to crumble. I’ve got plans.”

I knew right away that I would use this woman in a part, but it took a while. When I did Absurd Person Singular [by Alan Ayckbourn], I styled her somewhat on this woman. The hair; the clothes; the certainty of all things even as she veered and listed on her heels. She was convinced of all things. You can’t try to be funny. We’re all funny enough. People laugh at me all the time, because of how I look and talk and think. Someone somewhere is probably preparing a characterization on me. I can’t wait to see it!

Credits:

These quotes are from phone interviews conducted by James Grissom in 1985.

Photo credits: Michael Tighe; Geraldine Page in Woody Allen’s Interiors, in 1978; Geraldine Page and Richard Thomas in Strange Interlude, 1963; Darren McGavin and Geraldine Page in The Rainmaker, 1954; Geraldine Page in Separate Tables, 1957; Geraldine Page in Sweet Bird of Youth, 1959; Geraldine Page in Absurd Person Singular, 1974.

Lovely!

Priceless truths revealed! Thanks James, and thank you Geraldine!!