Garson Kanin on Ronald Colman

"If you have any romantic notions about Ronald Colman, I’m here to tell you that there will be no disappointment."--Garson Kanin

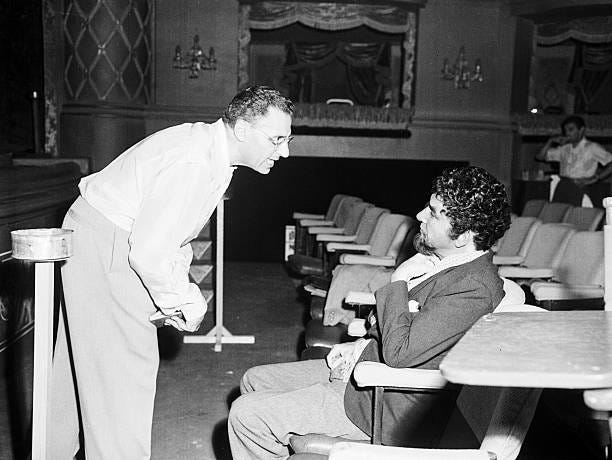

Marian Seldes was kind enough to allow me time with her husband Garson Kanin, to ask questions and to listen to him talk about his work in films and theatre and books. This conversation, from 1995, took place after Marian had given a performance as Willa Cather, which you can now find on audio.

I asked Mr. Kanin about A Double Life, written with his wife Ruth Gordon and directed by George Cukor. My first comment was that the work of Ronald Colman had not aged: He was not histrionic or stagey, as many of his contemporaries now appeared. Kanin agreed.

No, Ronald Colman is real and he is still wonderful today because he played to the situation, never to the camera or the director or any imagined critics. Irene Dunne was similar: Her work is clean and clear and works in the context of the day. I watched her not long ago in I Remember Mama, and there is not a false note. She is universal. She is a mother. When she manages to get to the bedside of her sick child in the hospital—you know, pretending to be a maid and moving toward the bed with a bucket of soapy water. I mean, it’s lovely. It is not artificial. And then she sings to the child. She has kept a promise. Her word is her bond. George Stevens directed that, and he was tough. He was not overtly sentimental, but his films will tear you apart. He knew how to get to the heart of the matter, as Ruth said. She said, “He finds the best part of the meat.”

George Stevens also directed Ronald Colman, and he praised him to the skies. If you have any romantic notions about Ronald Colman, I’m here to tell you that there will be no disappointment. He was a professional and a gentleman. I had precisely one—I don’t even want to call it a problem—but I had one issue with Ronald.

Ruth and I had written our script in the hopes—the dreams—that Larry Olivier would play the part [of an actor whose obsession with the character of Othello bleeds, tragically, into his private life]. Larry indicated he was interested, but he was pulled in many directions. He was about to make his film of Hamlet, among other things. Larry was kind, but he declined. We went after Ronald, who was enthusiastic, and after a meeting with me and Ruth and George, he was ebullient. George then did something he instantly regretted: He let Ronald know that Olivier had been the first choice for his part.

With his usual superb manners, Ronald reached out to me—I think he had some understandable trust issues at that point with George—and said he couldn’t do it. He was no Larry Olivier, and he understood that Ruth and I had some very high expectations for the role, and he didn’t feel he could meet them. I talked to Ronald. Ruth talked to Ronald. He kept his word. His word truly was his bond. I spoke to George, and I told him he had some work to do to regain Ronald’s trust. George behaved well, and he was a wonderful director.

What I want to point out is the generosity of Ronald Colman. Shelley Winters had—as she claims—her first important role in A Double Life, and her scenes were poignant and funny, until tragedy arrives. Shelley was very nervous. I find that Shelley is always very nervous, unsure of herself, no matter how she appears on talk shows and in interviews. She worries terribly about being good. Shelley was enamored of Ronald, and Ronald treated her with such gentleness and respect. I use this term a lot about actors: He gave scenes to Shelley. He never treated her as anything but a peer, and he would lead her in a scene so that she was the focus, and George followed. Ronald also did this with Signe [Hasso]. He did it with everybody. Ronald said several times that if the film doesn’t work, nobody works. No performance can survive an imbalance of attention. Watch those scenes of bemusement Ronald has with Shelley in the restaurant.

Ronald won the Oscar for A Double Life. I think he deserved it. George was nominated, and I think he deserved it. Ruth and I were nominated, and I sort of think we deserved it. Shelley was not nominated, and I think she should have been. Robert Osborne was placed in the unfortunate position of having to tell Shelley that she had not been nominated for an Oscar, and she was flummoxed. “Are you sure?” she asked, of the man who knows more about the Oscars than anyone. He told her he was quite sure, then read the names of those nominated that year. “Well,” Shelley said, “I should have been nominated!”

I agree with Shelley. There was a tribute to me and my brother at the Museum [of Modern Art] a few years ago, and Shelley insisted on coming, and she gave a lovely tribute to me. I adore her, and afterward Marian and I went out with Shelley. What did we talk about? Ronald Colman. “Why aren’t they making Ronald Colmans anymore?” Shelley asked. Good question.