IN the movie industry which is, according to the latest contract, fabulous for exactly forty-four hours a week, heroes arrive by special delivery, like publicity releases, and die of dropsy of the option. But every ten years a lasting legend emerges. One of these is a man whose name evokes beauty and box-office blooming as a twin boutonniere from the brutality of a leather jacket: Elia Kazan.

Early last year I went to visit him at work. The master’s magic was coming to pass on Avenue M near 14th Street in deepest, most domestic Brooklyn. The building looked like a staid cross between a hospital and a barracks, not like the Warner Brothers’ East Coast studios. The hand-lettered sign on the door, Newtown Productions, Inc., promised some bourgeois textile activity instead of the independent company of a famous movie maker now completing an Oscar candidate called Baby Doll.

But the moment I entered, I recognized glamour by the fact that it was policed. I had to pass a number of vaultlike doors hung with posters that hissed Silence! and manned by policemen who emanated as forbidding an air as is compatible with absorption in the Daily Mirror.

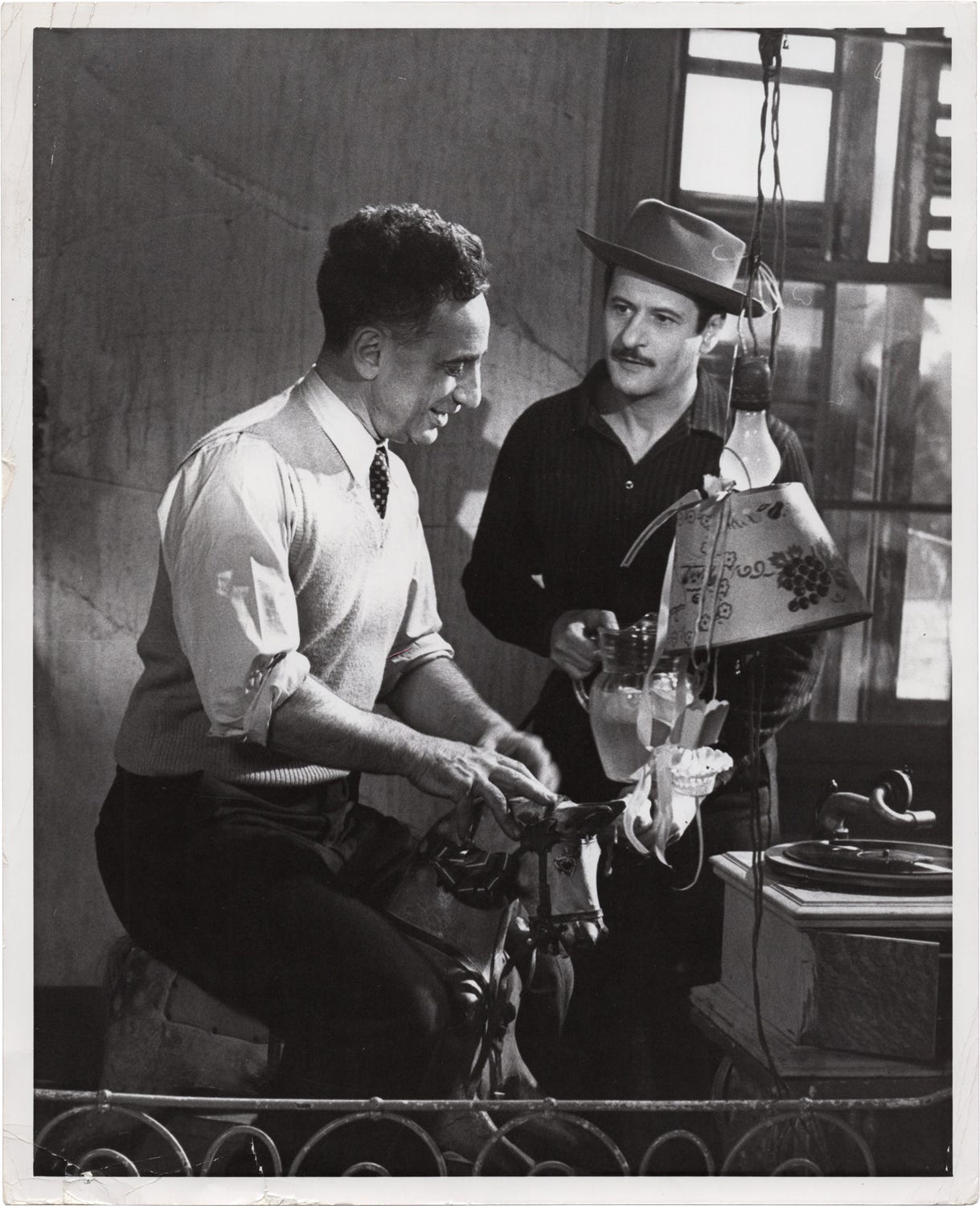

When I finally reached the inner sanctum of the sound stage, all was gaiety and chaos. Dozens of spotlights focused on a mildewed attic that had been erected in the middle of the set. A window, complete with shutters, hung surrealistically in the air, and a member of the camera crew maneuvered it against a baby spot, shouting for better shadows. Carpenters hammered, electricians strung cables, a girl in a pink slip gestured to herself, a booted bravo whom I recognized as Eli Wallach murmured lines at his whip, pigeons whirred through the air and stagehands swung through the high scaffoldings to wave huge nets after the birds and trap them with triumphant howls.

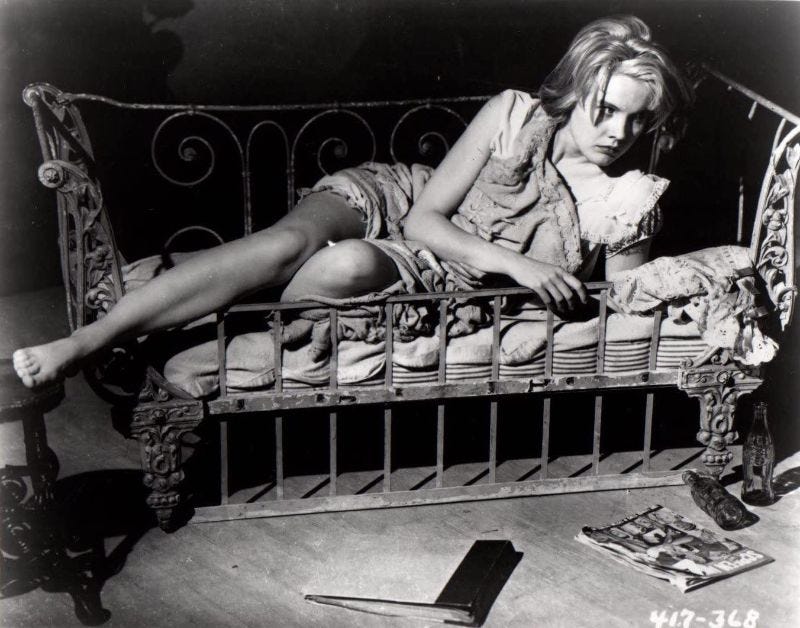

The attic was a replica of the one in Benoit, Mississippi, where the bulk of the picture had been shot. The Tennessee Williams script (derived from, but no longer resembling, his short play, 27 Wagons Full of Cotton) had Karl Malden, a middle-aged cotton-gin operator, living in the town with Carroll Baker (the pink-slipped, muttering girl) as his wife, twenty-five years his junior. Eli Wallach not only romances Baby Doll, but also sets up a newfangled cotton gin which puts Malden out of business. Malden, in turn, burns down Wallach’s gin. The scene now to be shot (the script girl explained to me) was to show how Wallach chases Baby Doll through the crumbling attic and forces her to sign a confession of her husband’s arson.

Just then a man darted out from under the roof trestles. He wore Brooks Brothers pants and a Stillman’s Gym sweater. He was small, but his hammer-brandishing hand was sized and muscled to fit a stevedore twice his weight. His hair was black Mediterranean thistle, and his stubble had the look of belonging, as though it had often flourished on that hard jawline before. He could easily have been tagged as a tough Sicilian fight manager. And yet the way he dropped the hammer and accepted a saw, the way he stood pensively sovereign for a moment amidst the steady bustle before vanishing again—all that suggested swarthy and informal royalty, a slightly shaven hobo of a Haile Selassie.

He lacked all the panoply of directorhood, from black beret to bossy bark. Yet this was Elia Kazan, called Gadg by friends or candidate-friends, Pasha by Sir Laurence Olivier, and Elia by nobody; owner of two Hollywood Oscars and director of plays which were awarded three New York Drama Critics’ Circle awards; catalyst to fame for Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, Marlon Brando, James Dean, Jack Palance, Eva Marie Saint; top dog, in terms of money magnetism and critical esteem, on Shubert Alley as well as in Beverly Hills. The average show-business genius needs a lifetime to reach any of these eminences. This Turkish-born son of a rug manufacturer breezed past them all before leaving his middle forties. But a man's personality isn't as accessible as his statistics. What was the connection between the rumpled figure and the marquee magnificence? And why did the sorcerer perform in a sweat shirt? To escape the sterile glitter of the summit—the “catastrophe of success,” as Tennessee Williams has styled it? Or only to establish a useful professional façade, a deliberate and lucrative trade-mark? I would watch and I would wait—first of all for him to crawl out again.

Which, a moment later, he did. He went to the girl in the pink slip and put his arm around her confidingly, like a sorority friend. “We just notched this attic beam a little more for you,” he said, “so the whole thing is going to give a little more when Eli gets mad. You're not going to fall through, honey.” He kicked the solid but invisible floor beneath the “attic” surface. “But it’s gonna give you a better feel of falling.”

Carroll stretched herself trembling along one of the few solid beams visible and clung to it.

“You poor darling,” Kazan said, and with a playful stroke brushed a bit of her hair into her face.

“I can’t see, Gadg,” Carroll cried.

“That’s why I said you’re poor.” He laughed, and suddenly shouted hoarsely at the stagehands, “All de boids caught?”

“Yes, Gadg.”

“Ready to make with the dust, Logan?”

“Ready,” said a stand-in with a bowl of dust.

“Lock it up, fellas,” Kazan said, throwing a piece of wood up into the air and catching it.

“Lock it up!” yelled Charlie Maguire, the first assistant director, and the red light flashed on over all the doors.

“Give us three bells, huh?” Kazan said.

“Three bells!” shouted Artie Steckler, second assistant director.

A buzzer sounded three times. The hammering ceased, the talking died, even the faint clicking of the typewriter from the office upstairs stopped like an abruptly broken watch. Everybody froze into silence and immobility. Only the sweat-shirted little man who now stood next to the camera was alive. The entire building, with its high-powered personnel and fantastic illusion-making machinery, was in the palm of his hand.

“Action,” Kazan shouted, and opened his arms wide, winglike (three stagehands released nine pigeons), and then made like a pitcher (the stand-in started to throw dust against the attic roof). And, amidst a flutter of wings and rustle of particles and a moaning and sighing from the prostrate, blinded Miss Baker, Wallach, standing a few feet away from his victim, began to stamp and earthquake the old attic and to demand that she sign the statement. He tacked a piece of paper onto a nail at the end of a pole, attached a pencil to it, reached it over toward the girl.

All the while, Kazan repeated in soundless pantomime Wallach’s snarls and stomps, Carroll’s squirmings and jerks. With finger motions he directed the stagehands shaking the “attic” springs. He nodded to the sound man, who moved the mike boom suspended above the action. He encouraged or soft-pedaled the dust thrower. He was a demon in constant joyful contortion, the very gremlin soul of make-believe.

Carroll meanwhile had signed the paper. Wallach retrieved it, kissed it exultantly. Then suddenly the scene became less fierce, more tender. Wallach took a long look at the girl; the dust drizzled down like gentle rain; Kazan’s lips moved in a sweet, slow, silent rhythm. Even the pigeons flew about languidly, as though they were bona fide Actors’ Studio members improvising wistfulness. Wallach tacked a clean handkerchief to the pole, reached it to Carroll with a gallant gesture. She hesitated, gave a ghost of a smile, took it and dabbed her eyes with it.

“Cut,” said Kazan. He suddenly threw himself down headlong on an attic beam parallel to Carroll’s. “Baby Doll,” he said as one prostrate person to another (he even pushed some of his hair into his eyes), “Baby Doll, when he reaches you that handkerchief, it’s like something very nice but unexpected. It’s like something out of your childhood, something beautiful and unexpected like an Easter egg you suddenly found. Even touch it like an Easter egg—careful, so you won’t break it, see?”

He stroked her cheek, then jumped up and called to Wallach in a rough man-to-man voice, “Eli, you old bastard, let’s do it like you kiss that piece of paper not because you’re grateful to her, but because that signature of hers is gonna break her husband. That kiss means ‘Now I got him by the testicles!’ And do some business that shows it.”

“Some business?” Wallach asked.

“Yeah, you’ll figure out something,” Kazan said with a confident shrug. Wallach kissed an imaginary piece of paper with a gloating growl that came up from his guts, and then spat.

“Great!” Kazan said with jubilation. “Roll it!”

The scene was shot again. This time Wallach spat (and Kazan spat soundlessly with him) and Carroll took the handkerchief with marveling wonder while Kazan’s hands cupped tenderly to form an Easter egg.

“Cut!” Kazan said, and instantly began to throw tiny pieces of mortar at Wallach’s feet. “I want to annoy you, Eli boy. I want to get you mad. Come on everybody, that first shot again!” He grinned and continued to throw bits in Wallach’s direction. “I’m gonna bombard the hell out of you until you show us you’re really fighting crazy for that signature. I’m gonna stone you. . . . Action!”

He kept up his fierce throwing motions while his leading man went through the attic-stamping part of the scene again, but more intensely now under the waggish volleys. “Cut!” Kazan shouted. “Perfect! Print 3 and 4. Lunch!”

“He’s got a knack for making a fascinating game of it all,” Karl Malden said over a shrimp salad five minutes later. “You forget it’s a big business, a tough business.” He lowered his voice a bit. “I’ll give you a for instance: He’s way above budget on Baby Doll. It’s his own outfit, it’s his own finances that are involved. Thousands of extra bucks a day. But it doesn’t cramp his style at all. You’d never know it.”

“He’s a good actor,” another company member said, slow and hard. “He puts up a good show, all right.”

“Listen,” Malden said, “if being a grand guy were all there is to him, he’d still be an assistant stage manager. Sure, he’s shrewd and subtle. I’ll give you a for instance. In Streetcar I played Mitch, the guy who gets sort of sweet on Blanche du Bois. At one point she asks him, ‘Do you love your mother?’ I’m a Mama’s boy, of course, so I say, ‘Yes, very much.’ “Now, the first week of rehearsal I couldn’t do anything with that, it was a nothing line. And one day I’m going through it again when I look up and see Gadg pull the most terrible teeth-gnashing face. I said, “What’s the matter?’ And he said, ‘Did you watch me? That’s how you should feel when you say that line. Because you hate your bloody mother. Sure, you have to say you love her—you even have to think you do. But deep inside you know she’s got a double nelson on all your emotions and she’s the reason why you can’t develop and mature.’

“I suppose he’s been a buddy to Carroll by wearing her to a frazzle,” the other company member said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“He’s been notching those attic beams a little more with each take. The girl’s been getting hysterical, she’s so afraid of falling.”

“It’s a pretty intense scene,” Malden said.

“He doesn’t have to squeeze the intensity out of her by torturing her,” the other company member said. “Did you get how he pushed the hair into her face?”

“Take it from an old pro,” Malden said, “she’ll have forgotten the physical discomfort long before the picture is released and she finds herself a star. In Waterfront I really got belted as the priest. I don’t remember my black-and-blue marks. I remember my Oscar nomination. And I’d rather a director inflicts physical discomfort on you than indignity. With Gadg you can be sure indignity won’t happen. Did he ever let Carroll know that she’s a newcomer? No, he only let her know that she has loads of talent, which she does. The same with me. Before other directors I say to myself, ‘I’m a professional. I’ve got to watch out for my reputation.’ With Gadg I don’t mind falling on my face. He’ll just say, ‘Okay, let’s try it different.’ With him I take chances.”

“That’s how he gets more out of you,” the other company member said. “Time!” Artie Steckler shouted from the next table.

We went back to the studio. The attic lay deserted. Camera crew and stagehands now populated a set representing the worn, greasy interior of a Mississippi café. “He’s rehearsing the farmers,” Malden told me.

The farmers, I found out, were Mississippi planters who had been flown up from the Delta country the day before. Until Baby Doll they had never acted in their lives. Kazan had come across them on location, liked their looks and made actors of them overnight.

“How?” I wondered.

“Watch,” Malden said.

The four of them sat around a café table, and Kazan sat on top of it, legs dangling. “Jeez, fellas,” he said, patting his stomach, “they sure can’t make pizzas no more in New York.”

Apparently he had been to lunch with them to warm them up. He did not condescendingly imitate their speech. He talked as if he had been raising Delta tobacco all his life.

“Now, this here thing is just gonna be a run-through, fellas, just to see how the damn thing works out on the set. You-all know your lines, and anyway we’ll start worryin’ ’bout that tomorrow when we shoot it. Now just get the feel of it. Charlie-boy, you go to the door and stay there a-leanin’. The rest of you stick. Ease back into the chair a little more, Eades—you’re the sheriff. Now, when he comes in—” Kazan called out loud in his Eastern voice, “Eli!” and Eli Wallach entered. “Now, when this interloper comes tryin’ to stir up a fuss just ’cause his cotton gin’s burnin’—why, you set back and smile and give him nothin’. Go ahead.” Wallach came up to the “café patrons,” demanded justice, was blandly refused, went up to “Charlie-boy,” became more incensed, stalked out.

Kazan straddled his legs across a chair. “We’ll go at it again. Now, when he comes at you-all, you know what you’re thinkin’. You’re thinkin’, ‘Why, that little outsider bastard! Speculatin’ there’s somethin’ wrong with the Delta police force! Now, ain’t that mighty cheeky!’ Go ahead— No, wait, hold it a spell.” He went up to Charlie-boy at the door. “Charlie-boy, somethin’ botherin’ you?”

“Well. . . .” Charlie-boy said.

“Somethin’ bothers you when Eli says, ‘Everybody’s so happy it’s like a rich man’s funeral.’ Right?”

“Well,” Charlie-boy said, “he’s holdin’ my jaw while he’s sayin’ it.”

“You just keep grinnin’, Charlie-boy. You grin right through him.”

“But I feel like doin’ somethin’.”

“That’s the boy; always tell me what you feel like doin’!”

“Push his hand down,” Charlie-boy said.

“Sure,” Kazan said. “Push his hand down. Good idea. But keep grinnin’.” He turned to the script girl, resumed his Eastern voice. “Charlie-boy pushes Eli’s hand down. Put that in, Bobby.”

“We are ready for the singing scene,” Boris Kaufman, the cinematographer, said.

“Great,” Kazan said. “Let’s watch Jennie sing.”

We all walked to the other side of the “café,” where the spotlights, huge black cuckalorises (shadow-throwers) and mike boom bore down on a tiny colored woman.

“Jennie!” Kazan said, and took both her hands in both of his. “We’re goin’ to have some fun now.”

“Yessir,” Jennie said.

“Hey, Jimmy, Bob—” Kazan shouted at the light crew and shielded his eyes against the glare. “How about taking it down a couple of points? I wanna go easy on Jennie.” He turned to Kaufman. “Think we’ll still have enough definition?”

The two began to work with light meters and camera finders. Meanwhile I asked Jennie how she had gotten into the movies.

“Mr. Gadg,” she said, “he have dinner at Mr. Charlie’s, yessir.” Every statement came complete with yessir and careful smile.

“You mean Charlie-boy over there,” I said.

“Yessir, I’m his cook,” she said. “And Mr. Gadg, he hear me sing.”

I asked her if she had ever been in New York before.

“Never been away from the kitchen more’n a day,” she said. “Yessir.” Kazan came over. “Jennie-girl,” he said, “remember, just like the rehearsal. When I say, ‘Action!’ he—” Kazan pointed to the “sheriff”— “he’s gonna say, ‘Come on, Jennie, sing us a song.’ Go on, say it, sheriff.” The sheriff said it. Kazan continued, “And then you’re gonna give him the pizza—that’s right, like that. And then—No, you’re not goin’ to look down, you’re gonna look straight at Mr. Charlie. I’m settin’ him on the camera stool for you, and then you’re goin’ to sing your song with all you’ve got. Okay?”

“Yessir,” Jennie said.

“Fine,” Kazan said. “Let’s lock it up.”

“Lock it up!” Charlie Maguire yelled.

“Three bells!” Artie Steckler shouted. The buzzer sounded three times. The world fell silent.

“Roll it,” Kazan said.

“Scene 35, take 1,” the second assistant camera said.

“Smoke it up!” Kazan hissed, and everybody—stagehands, prop men, actors—blew cigarette smoke around Jennie to give the scene a café haze.

“Jennie!” Kazan whispered, and held his clasped hands above his head in encouragement. Jennie took the pizza from the kitchen man.

The sheriff said, “Come on, Jennie, sing us a song.”

Jennie put down the pizza and sang her song.

Kazan put his forefinger over his eyebrow and waited till the song was finished before saying, “Cut.” He came to Jennie, put his arm around her, “Jennie, you ain’t singin’ the way you did down in Benoit. You got only half of yourself in that song. You’re among friends, Jennie. There’s your Mr. Charlie right here. Don’t look down, look at him.”

“Yessir,” Jennie said.

Once more the scene was shot. Once more Kazan put his arm around her. “We’re gettin’ closer, Jennie. Gettin’ more used to the lights. But we haven’t got it yet. This time we’ll do it, honey, right?”

“Yessir,” Jennie said.

This time Jennie had barely finished the first five bars when he yelled, “Cut!” He went to Charlie-boy, took him behind the set, came back alone. Then he led Jennie to her chair again. She sat down and he knelt in front of her and, as before, put both her little hands into his.

“Jennie,” he said, “listen. Mr. Charlie went down for a pack of cigarettes. I’m gonna sit where he used to sit. And you’re gonna sing that song for me. I’m not your boss. I’m your friend and I need you. I wanna make a good movie, and I just can’t do it without you. When you sing that song, think of that. And think of all the poor friends you have. Some are sick, some are sinners, some are just plain in trouble ’cause things ain’t always so easy for your folks down where you live. So sing for them. The song’s for them, and a little bit the song’s for me too. So don’t look down when you sing it. Look at me. It’s such a beautiful song.”

“Yes, Mr. Gadg,” Jennie said. For the first time I saw her lips move.

“Action!” Kazan said, sitting on the camera stool.

Jennie received her cue, put down the pizza, and all of a sudden she lifted her head, and her pretty, slightly wizened face inclined toward Kazan and gleamed alive. Her voice was small and flat, but it rang out unafraid. She began to make small emphatic gestures with her hands— probably the kind she’d been taught in the church choir—and her voice swelled and encompassed all the formidable apparatus around her and all the high-powered people, the least of whom earned more in four days than she in six months. Her small voice queened it over all of them, and I saw a watchman at the farthest door drop his newspaper and listen.

“Cut!” Kazan shouted when the last notes died away and, as even the stagehands applauded, he ran up and kissed her.

The following night the whole company moved to Long Island in order to shoot the exterior of the Delta Café. The real-life café down South had been so excited by the prospect of their property’s celluloid canonization, I was told, that they had redecorated themselves out of the background-for-Tennessee-Williams-movies business. Dick Sylbert, the art director for Baby Doll, had to comb the metropolitan area for two days until he found a café with a Mason-Dixon chimney and suitably shabby slat walls—in Floral Park, near the New York City line.

When I arrived around midnight, the generators on the company trucks were humming; the huge spotlights beat down on the carpenters finishing the false door, on the false neon sign, and on the extras rehearsing for their street-fight scene with Eli Wallach. All around, the sleep-roused citizenry of Floral Park pressed against police ropes and rubbed eyes at the wizards’ invasion. I went into the café. Kazan was playing the pinball machine, with grave concentration. Then he shouldered his way out. He made straight for Charlie Maguire, said something to him. At a gesture from Maguire the extras disappeared.

“The hell with the fight,” Kazan said. “Bobby, change the script. There’s just going to be Eli coming out of the café, like this.” He acted it out. “And finding Lonnie (Lonnie Chapman, Wallach’s side-kick in the picture) beaten up. And leading him away like this. And we won’t even show all of that. We’ll have a lot of people rushing out the door, a lot of shoulders and heads blocking the camera. A lot of pressure and intensity. Like this. The hell with another silly movie fight.”

And, “like this,” he began to orchestrate extras and actors. At one in the morning the company was finished.

At eleven in the morning I was sitting at Burl Ives’s bedside, discussing the improvisation. Ives was perfectly healthy, but thought it indecent to be out of bed at so early an hour.

“Improvisation,” he said, “that’s the boy’s specialty. I’ll tell you about a hell of an improvisation in East of Eden. I was the sheriff in the picture, and at one point I had to stop a mob from lynching a German. So we were setting up the scene, with me coming in, gun drawn, when all of a sudden Gadg says, ‘Goddam! Goddam! I hate to have you come in with that equalizer sticking out, acting Lone Ranger tough. This isn’t that kind of movie. This mob consists of people who have respect for you. There’s something else you ought to do.

“It stunned me. There was no reason to drag my father into it. The only way I can explain it is that Gadg must have read my autobiography, where I kept writing about my father without knowing that I did. Anyway, he asks me, ‘What would your father do?’ And I told him that he would have said, ‘I think that’ll do.’ And Gadg said, ‘Put it into the script.’ And that’s how it worked. I come in while they’re brawling on the German’s lawn, and I say, ‘Hello, Mr. Smith, Mr. Jones. I think that’ll do.’ Quietly. It stops the riot. It’s one of the most effective scenes.”

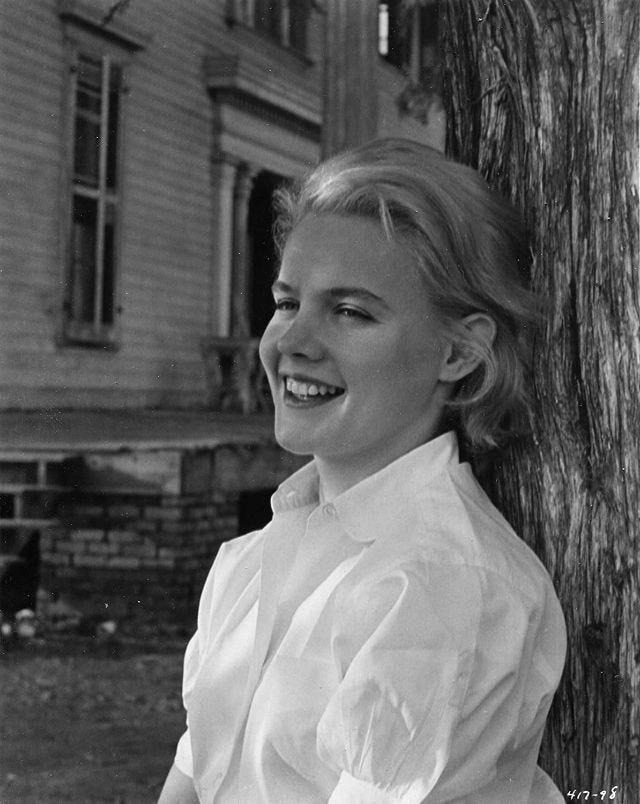

When I visited the set next morning, the press had been admitted and the air was festive with solid ties from the Times, brisk bow ties from Time, and suavely cynical pipe smoke from The New Yorker. Kazan nibbled a popsicle while Mildred Dunnock was on camera, and I abducted Carroll Baker for a drugstore sundae. The place was awash with teen-agers, and nobody gave her a tumble. “Several months from now that won’t be possible any more,” I said.

“I know,” she said. “I don’t want to think about it.”

“How did it all happen?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” she said. “Gadg is so weird that way. I still have no idea how he picked me. He saw me in one little part in Giant and in a featured role in All Summer Long, which was a Broadway flop. And I ran into him once when I took Lee Strasberg’s private classes. Then one day he asked Jack (Carroll’s husband, Jack Garfein, now directing Ben Gazzara in Sam Spiegel’s film, End as a Man) if I could act. Jack said, ‘You’ll have to find out for yourself.’ The next week he calls me and says he has a part in mind for me and why don’t I come to his office. I do, and he tells me he’s seen me in a kind of sophisticated part in Giant. Could I do a naïve girl with my hair all mussed up? I said, ‘Sure.’ He said, ‘Good.’ He gave me the script. After a few days he calls me and asks if I’ve read it and if I want to come talk about it.

“I come up, and he asks me, ‘What kind of girl is Baby Doll? Talk to me as if she were a girl friend of yours.’ Well, I’d developed all sorts of ideas about her, and I discussed them. Then he became a little more specific. He said, ‘Does Baby Doll respond to Vacarro (Eli Wallach) just physically or does she have real feeling for him?’ And I said, ‘She’s all mixed up, but she does have a real feeling for him.’ He said, ‘Wonderful.’ And only then did it come home to me. I said, ‘You mean I’m in?’ And Gadg said, ‘Sure.’ It was just absolutely incredible. I mean, I had read for four months for the small part in All Summer Long. And here was Gadg starting the first movie of his company, with hundreds of thousands of dollars of his own money involved, and putting me into the title role! Staking all that on someone without a screen test, without an audition, without me even reading one line for him . . . I was dazed.” On the wings of Miss Baker’s amazement we returned to the studio. The final scene (in the shooting schedule, not in story continuity) was filmed. Baby Doll accompanied her husband on a medical check-up that ended in comic confusion. There was mounting comedy on the set, but no confusion. Kazan produced a monumental cigar and barked guttural commands: “Aaakkktion!” or “Rrrroll it!” in imitation of a German movie director. Malden, cued to stick his head out of the doctor’s office, stuck out a skeleton instead. The crew kept erupting into muffled guffaws.

“Charlie,” said Kazan, “tell the gang to pipe down or at least tell clean stories. The dirty ones are too copulating distracting.”

More guffaws—and an even more successful take of the doctor scene. “There’s nothing he doesn’t exploit.” The low voice came from the cross-grained company member. “He left that merry sequence to the end so he can use the end-excitement to milk every drop out of the scene. That animal trainer! Uses their emotions like they were animals. He plays democracy with them like a trainer puts his head into the tiger’s mouth—for the good of the show. It’s all calculated. He lets them pat him on the back—and each time they do, they’re working for him.”

At the moment, though, Kazan looked more like a conductor than a trainer. With his baton-length cigar he slashed the air in a Toscanini caricature, then pointed it straight at the “doctor,” who had just gone through the scene with his shirt half unbuttoned.

“I’m gonna stop shooting, John, because your cleavage is showing. Wild track!”

Then they sat down on adjoining stools—Wallach, the whip-bristling brute, and Kazan, his longshoremanlike director—and mooned and moaned at each other with a sweetness Juliet might have envied. Carroll explained to me that this was a “wild track”—the sighs would be woven into the finished sound track of the picture.

“Ohhh,” trebled Wallach.

“Uuuuh,” trebled Kazan. “Give me an ‘Uuuuh. . . .’”

“Ouhhh,” said Wallach. They had to stop because everybody roared.

“Uuuuh,” from Kazan. “Ah, mine was perfect.” He laughed and slapped his knees with childlike glee. “Print mine.” He rose. “Yeah,” he said. “That’s it. Wrap up the picture.”

The shooting phase of Baby Doll, which had kept cast and crew working together daily for three and a half months, had ended.

A great shout went up. Everybody rushed for the drinks table. Everybody took snapshots of everybody else. Next they all made for the director. Kazan took them on one by one. And then a pixilated posse of the crew swept him up out of the studio, into Izzi’s bar across the street. There he drank, yarned, reminisced, laughed and rib-poked for an hour. He was a little smaller, stubblier and more muscular than the rest of them, but you couldn’t tell him apart in language or deportment until they took the Sea Beach subway express and he clapped his chauffeur on the shoulder and climbed into the Cadillac limousine. When he slumped down next to me, he looked his forty-six years for the first time (he’s forty-seven now).

“Not really tired,” he said. “Sad, I guess, to see the boys scatter. And wondering, as I always do when I finish shooting and all that press-and-publicity muck is over, whether it’s all been worth while, whether Eve got at least a handful of truth in half a mile of film. Because there isn’t only the press muck you’ve got to fight off. There’s the technical muck, the filters and light meters and cameras and spotlights. While all that matters is the actor. That little human thing you want to get at—that little moisture in the girl’s eye, the way she lifts her hand, or the funny kind of laugh she’s got in her throat—that’s what matters. And you never know how much of that you’ve caught until you see it. Sometimes you don’t even know then.”

He had lost the folksy authority he maintained on the sound stage. He spoke in a small dreamy voice.

“Did you notice the fellow who played the doctor? He’s no actor. He’s a lawyer, John Dudley. I don’t care what they are, little colored cooks, big-time real-estate lawyers like John, or a kid like Carroll. If they’ve got something—the shine and shiver of life, you could call it, a certain wildness, a genuineness—I grab them. That’s precious. That’s gold to me. I’ve always been crazy for life. As a young kid I wanted to live as much of it as possible, and now I want to show it—the smell of it, the sound of it, the leap of it. ‘Poetic realism,’ I call it when I’m in an egghead mood. Like the doctor’s scene we shot. I didn’t want just another consultation-room scene. I had the doctor play checkers—not even play it, but just have a lost game set up on his examination couch and brood over it. Because that’s the way an office is down South— people just waiting, outlasting the heat, looking out across the street and watching the saloon door swing in and out. I wanted to get all the Delta air I could into that little scene in the consultation room.” He sat up. We were stopping before the Astor Building, where his office was. “Hell, I must be tired,” he said, “running off at the mouth like that. Give me a ring in a couple of weeks. I’ll show you my favorite place. A better place for talking than this—” He pointed at the bright caldron of Broadway which, a moment later, swallowed him up.

His name, though, gleamed from the marquees through day and night. The following week its mention roused Deborah Kerr from a ladylike repose in her hotel suite.

“Gadg?” she said. “The next thing to God. He’s an angel to his actors. No rank-pulling, you know, no ridicule—and ridicule is our deepest fear. He’s quite a bit of a psychologist too. D’you remember the final scene in Tea and Sympathy? I’m beginning to unbutton my blouse to commit heroic adultery and show the boy he’s really a man? Well, it’s a pretty delicate business—the thing I was most afraid of in the show. We were all astonished when Gadg didn’t even talk about it the first weeks of rehearsal. But after a while we forgot about it because we were so busy with the rest of the play.

“When we finally came to the end, he said, ‘Go ahead. You’re inside your characters. You know what to do.’ So we did it, just by obeying what was inside us, John Kerr and I. Without direction. And Gadg said, ‘Fine. That’s the way it will stay.’

“You see, Gadg made me realize that in some ways my role was literally me. I don’t go around saving young men all day, as the heroine does in the play, but I’m full of compassion for stray dogs, lost cats and lame pigeons, and I didn’t even know it until Gadg told me so.

“I didn’t even know that I could handle an American part. In From Here to Eternity I played an American wife, but in a film you can always dub out a Mayfair syllable and dub in a Minnesota twang. You can’t cheat in a play. But all Gadg said about my accent was, ‘Oh, that. Forget it.’ He’s get an attitude of taking you by the hand, and leading you inward to yourself, into what’s important for the play and for you.”

Kazan’s genius has been something of a time bomb. It was around for a considerable time before it went off. Constantinople-born, of a Greek family that has been living on and off rugs for generations, he arrived in this country before reaching school age. After graduating cum laude from Williams in 1930, and after a term at the Yale drama workshop, he drifted through seven unspectacular years with the Group Theater, stage-managing and walking-on.

In the late Thirties and early Forties he began to act with sting and success, notably the taxi driver in Waiting for Lefty and Fuseli in Golden Boy—both plays by Clifford Odets. But all that ended when he directed Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth, the Broadway miracle of 1942. He had become a big-timer. Yet the plays he staged immediately afterward were still not the kind one associates with his name today: musicals like One Touch of Venus, comedies like Jacobowsky and the Colonel.

Enter 1947. Kazan directed All My Sons and A Streetcar Named Desire in New York, filmed Boomerang and Gentleman’s Agreement in Hollywood. In that year the bomb exploded. Elia Kazan became Elia Kazan. He not only displayed a stunning ambidextrousness by gathering for this year’s production an Oscar on the West Coast and, simultaneously, a Best Broadway Director award in the East; his work also defined the qualities that have become his singular imprint—the shattering, clawlike fierceness of his stagecraft, the fine translation of social texture, his hard-muscled and yet lyrically susceptible realism.

From then on nearly every production in his charge left behind the impact that was his signature. Death of a Salesman arrived on Broadway in 1949, Camino Real in 1953, Tea and Sympathy in 1953, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1955. He put Streetcar on film in 1950, On the Waterfront in 1954, East of Eden in 1955 and, finally, Baby Doll in 1956.

When I visited him some three weeks after our limousine ride, his office had already been turned into a preparation mill for his next picture, A Face In The Crowd, based on a Budd Schulberg short story. I asked him if this was the “favorite” place he had mentioned earlier and he said, “Hell, no. I’ll take you to it.”

Ten minutes later a taxi had brought us to his remodeled brownstone house in the East Seventies. There he vanished, typically supersonic, while his handsome wife Molly showed me through three floors.

We passed the master’s study on the top floor, featuring a huge drafting table, a big bulletin board, even bigger pictures of Kazan’s grandparents, and no Oscars.

“The real, get-away-from-it-all work he does in Newtown.” Mrs. Kazan pointed to a picture of their 113-acre Connecticut farm.

On the way down we encountered Nick, aged ten, and Katy, eight. The big two (Judy, twenty, and Chris, seventeen) were away at school.

Just then the summons of the paterfamilias filled the house.

I found him in a darkroom in the basement. “I got a photographer buddy, Roy Schatt,” he said. “I built the whole damn room with him. He’s teaching me photography, printing, fixing, enlarging, the works.”

By this time my eyes had gotten used to the red light. Kazan was bustling about like a boyish poltergeist. Sometimes the dark bulb caught in his face an exuberance I had never noticed before.

“Look at my mother’s picture!” he said. “Last time I printed it, I couldn’t realize that wonderful arm of hers because the background was too white. Now look! I just shaded the enlarger image a bit. See all the values that come out?”

“Call from Mr. Lastfogel,” the maid said from outside. (Mr. Lastfogel is the president of the William Morris Agency.)

“I’ll call him back later,” Kazan shouted, and said to me, “Still wondering what my favorite place is?” he asked.

His voice had suddenly become lower. It had the limousine tone again, soft and visionary. “There’s nothing like a darkroom. It’s so pure. No lawyers, no agents, no production managers, no telephones. Just you and your work. Funny, when I’m all alone down here, I find I haven’t even started to do what I want. I want to do more movies than ever. In the theatre the director just serves the author. But a movie director can create. The camera is such a beautiful instrument. It paints with motion. Why, this whole country is still undiscovered in terms of the motion picture. Take the South. I could make five more pictures on it. Not the intellectuals’ South. Not the Sardi liberals’ South. But the South where the Negroes sit in the street all day long—”

“Call from the MCA conference room,” the maid said from the outside. (MCA is entertainment’s other giant agency.)

“I’ll call back later,” Kazan said in the darkness. “Hell, I’m just beginning to loosen up, with all my Oscars. I’ve alternated violence and tenderness for too long. I’m beginning to break out of my own formula—as in Baby Doll. I used to sit down and work out things in advance. Now I shoot more as I go along. I shoot as I feel. In the old days I had no confidence. Determination, sure—the determination kid, that was me. But I used to wait, to look for the good things to come to me, good jobs and good contracts. Now I’m beginning to reach for things. I’m coming to writers with ideas. I wish I were a writer so I could start at the rock bottom of creativity. I want to do a picture about immigration which has never really been done before. I want to do a picture on my people, the Greeks. I’m getting impatient. Maybe because I’ve got more confidence, maybe because there’s less time every day—”

“Long distance from the West Coast,” the maid said from outside.

He turned on the light. He sighed and blinked for a moment, like a little boy flushed from his hide-out. The next instant he was composed. With powerful steps he bounded past me and up the stairs.

“Well—darling,” he said into the receiver.

©Esquire