Elia Kazan on Theatre

The theatre is not what it once was, and it will never have the power it once had.

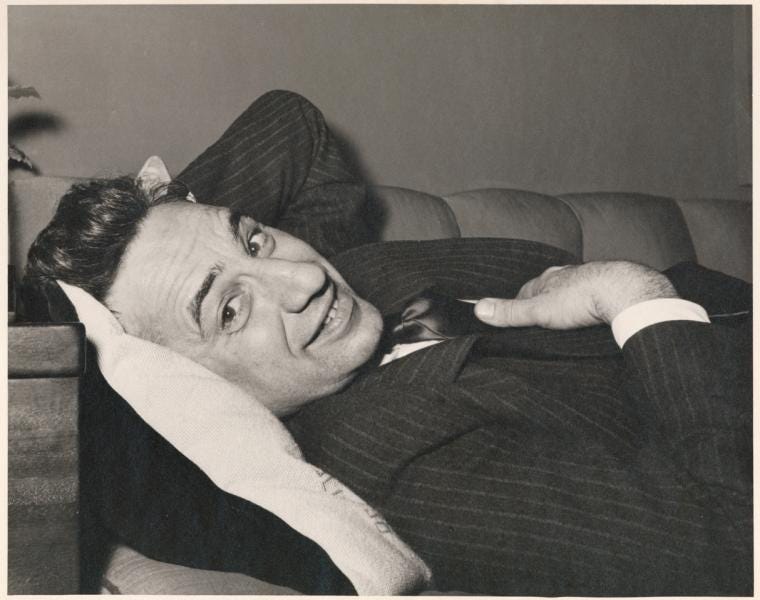

[A portion of an interview between James Grissom and Elia Kazan in 1993. The interview was first posted on jamesgrissom.blogspot.com in 2012.]

JG: Is it justified when people claim that the theatre is failing? That the theatre isn't what it once was?

EK: It could be a number of things, some of them dubious, some of them disingenuous, but it doesn't mean that the statements aren't true to some extent. The theatre is not what it once was, and it will never have the power it once had, but that is not simply because fewer talented people are working in it. The primary cause of the decline of the American theatre is the persistent decline in the desire of the American people--the American audience--to foster and to maintain a relationship with the theatre. Period. I also blame the proliferation of amateur theatres, the multitude of colleges that have departments for those who never will and never should have careers in the arts. It's now a business, a market, an income incentive, an engine of deceit. But there it is. Try getting rid of it. It makes for great income for playwrights--when and if the schools and the community theatres actually pay royalties--and it allows for some delusion in the provinces. Someone sent me a letter the other day with clippings, in which she was referred to as "the Vanessa Redgrave of St. Louis." I wish her well.

JG: But there are those who say that everyone has a right to participate in the arts.

EK: Define that. Of course a local meeting house can have dance classes, art appreciation, dramatic readings, but there is a location and a particular set of standards within that purview. What appalls me is that this democratization--which I believe should apply to local institutions that want to expose their communities to the arts--has spread to both the academic communities and all the way to professional theatre. It's what I would have to call the kumbaya effect on the arts: Let's hold hands and love the arts together. Aren't we great? Shouldn't we be honored and applauded just for attempting this? Well, no, we don't applaud attempts, or I would have a few Olympic medals for trying to run like Jesse Owens or trying to mount a gymnastic horse. Trying is good, but trying is what happens behind closed doors, in a studio, in a gym, in your dreams. It is not something for which admission should be charged and patience indulged.

JG: We'll go back to several things you said...

EK: ...I can just imagine...

JG: ... but I want to ask you why you believe that a relationship can't be fostered between the American audience and its theatre.

EK: Well, for one thing it is no longer accessible. It's far too expensive, and I can never get a straight answer as to why this is. The unions are blamed; actors are blamed; theatre owners are blamed. Perhaps they are all guilty--all I know is that I am a man of reasonable means, and I don't like paying as much for tickets as I often do. It's an enormous investment, and the plays are often poor, and the actors simply aren't well-cast or directed properly. Or maybe they're not any good. I don't know. But I've just spent several hours and several hundred dollars to examine the situation. And I get tired of it. Now, if I get tired of it--an old theatre and film director with money--how soon do you think the so-called average theatre- goer is going to get tired of it?

I also don't care for the proliferation of corporate theatres, non-profit sinecures in which a handful of people work on each and every play, decide the casting, put their fingerprints all over each production. Their plays get a texture, a taste, a smell, time after time. They dip into the same, small pool of actors, and suddenly your opportunities for excellence or inspiration are dwindling. I say this despite the fact that I was present at the abortive creation of the Lincoln Center Repertory Theatre. I should point out, however, that we should have one national theatre, and now we have a series of fiefdoms that are almost universally mediocre. We should have high standards, but even with high standards, there are more than five people available to work in any given category in our theatre, but every year it seems the same five directors get the work; the same five designers do the sets and the costumes; the same five or seven actors get the parts. I'll tell you why they do, and it's not because they're terribly talented: It's because they're terribly pliant; they don't cause trouble; they punch their clocks and learn their lines and smile at the patrons.

And this is one of the things that's killing our theatre.