Edward Albee: More Mystery Than We Can Realize

"I think there is more mystery than we can realize. I want to confront people with this mystery. I want them to question where they stand in this mystery. I want them to admit to their inventions."

Edward Albee once told me that he only trusted two women with what he called his theatrical soul: Elizabeth Ireland McCann, his frequent producer, and Marian Seldes, an actress who appeared in several of his plays, and to whom Albee felt he could ask anything or say anything. “Her love for me,” Albee said, “prevents any judgment from coming forward, and she has told me, when I have been wrong or cruel, often at the same time, that nothing, nothing, would ever separate us.” [Albee told me this after the death of Irene Worth, in 2002, and he admitted that he would have included her in his circle of trust.]

Marian Seldes was a vital part of my life from the time I met her—in November of 1978, at the stage door of the Music Box Theatre, when my high-school drama club from Baton Rouge High met her after a performance of Ira Levin’s thriller Deathtrap—and she possessed an extraordinary gift for friendship, enormous empathy, and an intelligence that she could share without ever resorting to cruelty. “I can sit with her and sort things out,” Albee told me. “She knows when to speak, and, beautifully, when to be silent.” When I told Albee that Marian had made my life in New York possible and better, Albee said, “That is what she does. Inexplicably, that is what she does.”

Elizabeth “Liz” McCann I knew only peripherally, through Marian and Albee, and from seeing her at theatres when I was with Marian, her “beaux,” and Liz would frequently ask me “Can’t you keep this woman home?” McCann could appear brusque and disorganized (she once sent Marian a letter that had ketchup stains on it), but her mind retained all things, and she could magically pull from a messy pile exactly what she needed. McCann loved the theatre and its people, and her word was solid: I cannot recall a time when anyone reported that she had rescinded an offer of aid or betrayed a confidence. Despite the appearance of brusqueness, McCann was generous, fully so, and when the actress Lois Smith and I went to the box office of the theatre where Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen was playing, McCann, one of the play’s producers, was in the box office, and flatly refused Smith’s attempt to pay for the tickets she had requested. McCann told the box office employee to offer house seats, telling Smith “I’m not going to let you pay for a ticket to a play of mine,” then to me, “And you, well, for some reason I like you.” That was Liz McCann.

Edward Albee considered Marian a close friend. As he told me once, in 2009, “Marian is incapable of dishonesty, and she delivers her statements with no judgment. She is unabashed by anything I bring to her. I find this mysterious—no, remarkable—and I need to be around her for these traits. These gifts.”

Albee and Seldes developed a sweet, bizarre vaudeville act: They would appear on panels, at celebrations, talk-backs after productions. Marian was always openly besotted with her brilliant playwright friend, beginning questions or comments with a breathy “Edward…” to which he would reply “Yes, m’dear” or “Yes, darling.” There were often disagreements between them, even in public, but they were gentle, and both were genuinely surprised by the other, curious to see where the argument went. At San Domenico restaurant one afternoon, when I was lucky enough to have lunch with the two of them, Marian said that she was often surprised “saddened, really,” by Albee’s insistence that relationships were almost always doomed. “It’s simple, sweet friend,” Albee said. “You had parents who loved you. You had parents who were happy to see you walk into a room. You repaired to a home that was full of memories and happy noises and smells. I grew up in a home full of silences and pressed linens and corners where I could use my imagination. Angry silences.”

Marian called me in the spring of 2008 to let me know that she would be in conversation with Edward at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Would I help her “produce” the program? I did not have an official role in the production, but Marian wanted my permission to read from comments both Tennessee Williams and Irene Worth had made about Edward, and she wanted me to be there, to be visible. Marian and Irene had a solid friendship, and they had been helpful to me in my writing, in helping me to meet people. Both Marian and Irene had told Edward about my book and the comments I had gathered. Edward and I met several times over the years, almost always with Marian present, and she always mentioned my book and that the two of us should get together. “In time,” Edward said, twice, and I assumed he was not interested. Edward Albee had a manner that could chill a room, and while he was always polite with me, I sensed that he had no interest in talking to me.

That changed on April 17, 2008, when Marian not only read some of the comments from my forthcoming book, but introduced me as someone “vital” to the afternoon’s event. I am reminded of this day in 2008, and of subsequent visits with Edward (always with Marian; he wanted her around) after reading Philip Gefter’s Cocktails with George and Martha (Bloomsbury), an excellent study of Albee’s play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and its life on the stage and as a film. In various interviews throughout the years, Albee had castigated Ernest Lehman, the film’s producer and what he called its “putative” screenwriter. Gefter’s contention is that Lehman was actually a sane and valuable steward of Albee’s play, although he did offer some ideas that both the film’s director—Mike Nichols—and Albee found repellent. Albee had admitted to Seldes, and would later confirm to me, that Nichols was in regular contact with the playwright as he was “protecting” his play.

For most of the program on April 17th, Marian and Edward spoke cordially, and the subject of the film version of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? only became a spiky subject in the questions-and-answer portion, when an effete man with a punchable face took issue with Albee over the score of the film by Alex North. Albee had criticized Lehman’s screenplay, and he also claimed that the swelling music in the film’s final scene was a detriment, a goading of the audience. The gentlemen arched his back and said “Alex North won the Oscar, did he not?” (In fact, North did not win the Oscar: John Barry’s sugary score to Born Free won the Oscar.) Albee replied, disingenuously, he later admitted, “I don’t know,” implying that Oscars won in the past did not earn a place in his mind.

This man infuriated Albee, and in the green room of the NYPL, his anger fresh, Albee turned to me and said “Let’s talk. The time is right.” I assumed that Albee meant then, that evening, and Marian was amenable to joining us, but Albee had plans, and so a date was set. A few nights later, we met at Marian’s apartment on Central Park South. Marian’s kitchen rarely held anything more than water, coffee, and bread, but for the evening she bought several bottles of sparkling water, and they were iced and sitting in two champagne buckets. (“Swankier evenings, don’t you know?” Marian said to me.)

I was early to Marian’s apartment, and as we sat waiting, Marian said “Ask him anything, darling. Don’t hold back.”

I will be providing this material over several posts. This material was not suitable for Follies of God, because none of it concerned Tennessee Williams and his relationships with the women who inspired him. I typed up the notes and showed them to Albee (as I did with all of my subjects), and he only changed those things he felt I didn’t write clearly enough. Albee asked me to delete one comment, and to “forget it forever,” and I did. That comment will never be seen.

Here are notes from that night in April of 2008 on Central Park South.

ALBEE: “What most disappoints me about Tennessee [Williams] is how strongly he needed and sought the opinions of those who know nothing at all about writing, about the theatre, about much of anything, quite frankly. We had so many conversations about this, and I think I was often impatient with him.

SELDES: “I remember your visit with him after we opened in A Delicate Balance.”

ALBEE: “Remind me.”

SELDES: It was about the Walter Kerr piece…

ALBEE: “Oh, that charmer. Yes. Walter Kerr and his exegetical fingering of himself. His showing off of T.S. Eliot, who was not the influence on that play that so many assumed. It always amused me that I was accused of imprinting homosexual characters and characteristics within my plays, a sort of inculcation, but Kerr wormed his Catholicism, his [Pierre Teilhard] de Chardin theories into dramatic criticism, which I found to be a form of mental illness. (Seldes interjected at this point, “Oh, Edward!”) Yes, Tennessee wanted to know if that piece hurt. If it was the dagger to my heart, because it was, you know, Mr. Kerr, who was so much more elevated an intellect than Stanley Kaufmann or the other men who prowled the aisles. I did not care what Walter Kerr thought, and not simply because he was so wrong about the play. Tennessee, however, began to quote from past Kerr reviews, and then segued into the [Robert] Brustein rebukes, which were as ugly and scabby as his complexion.”

SELDES: “I was so hurt for Tennessee when our production of [The} Milk Train [Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore] was dismissed. I was surprised how deeply he was hurt. I wanted to say, ‘But you’re Tennessee Williams! You’ll survive this.’ But do writers always survive?

ALBEE: “Not all writers, and it is asinine that a talent as great as Tennessee’s had to be inspected by so minor a group of people. This remains true today. Jerome Robbins was not reviewed by a a kid just out of his first or second year at ABT (American Ballet Theatre) or a recent Juilliard graduate, but I think he might have been better served by that kid than he was by critics who were never important to dance or music or theatre. Failure thrusts a critic into his role. I see now that critics apologize for being critics. They remind us that they are working on a novel or an opera or they will be directing in a theatre far from civilization. This means a very bitter, thwarted mind and heart has the work of real creators in their hands. Harold Clurman had a special niche in criticism. Clurman was a respected and busy director, and this was known when he was hired to write his criticism. It was not a secret. It was also fairly well understood that writing for The Nation was not going to make or break a play, in the way that a review in the Times could and still can. Clurman was a good writer and a good director offering his opinions on a production. He was not making points. He was not performing for the public, showing himself to be clever. He served the theatre, and even when I disagreed with him—and I did—I respected our conversations. I respected what he wrote.”

JAMES: “That guy at the event the other day…”

ALBEE: “That charmer…”

JAMES: “It really brought up the resentment, if that’s the right word, you felt toward Ernest Lehman…”

ALBEE: “…resentment is the right word. Would you like me to tell you more about it? Ernest Lehman paid a handsome sum for the rights to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Ernest Lehman paid himself a very handsome sum—I think half a million dollars—to allegedly write a screenplay. I think he made a quarter of a million dollars for the two lines he added to my play. He made known to me—consistently and brashly—that he wanted to make an ‘important’ film. I knew of Lehman for slick products—Hitchock, Audrey Hepburn, a fun melodrama like Executive Suite…

SELDES: “I liked Sweet Smell of Success…”

ALBEE; “…which I like even more after the ghastly musical version of it. This incessant urge to musicalize everything. I await the musical of what will no doubt be called ‘Who’s Afraid?’ It will, no doubt, arrive after I’ve died, because it will not happen while I’m breathing.”

SELDES: “I would see it.”

ALBEE: “You see everything.”

SELDES: “I do. When you’re right, you’re right.”

ALBEE: “Lehman admitted—confessed—to me that he wanted to be taken seriously. He felt he was a far better writer than had been acknowledged. The wealth was not a sufficient reward for what he had done, and now he would be seen as a ‘real’ writer. Had I cared more for Ernest Lehman, I might have asked him for his definition of a ‘real’ writer, but let me assure you that taking a play by another writer, which has already succeeded, and superimposing a couple of words, and then receiving an Academy Award nomination for this minor pasting does not make one a ‘real’ writer, and Lehman always inflated his contribution to my play and to the subsequent film.”

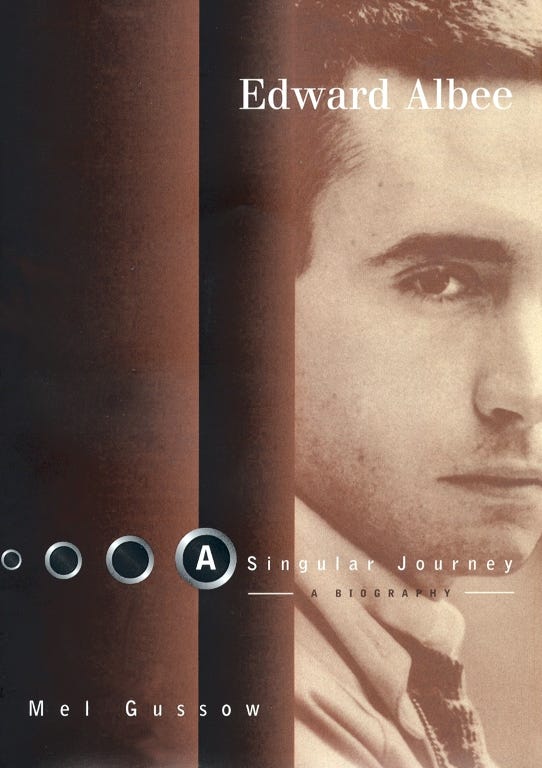

SELDES: “I thought Mel [Gussow] really wrote well about this.” [Gussow wrote A Singular Journey, a biography of Edward Albee that was published in 1998. Both Albee and Seldes contributed to Gussow’s study. Albee spoke to Gussow, and Seldes made available to him many letters that Thornton Wilder sent to Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon. Wilder was an early supporter, of a sort, to Albee.]

ALBEE: “But what was truly dangerous—and laughable—about Lehman were his efforts to revise my play, and I heard about all of this from Mike [Nichols]. It was important—if not pivotal—for Lehman to make the child of George and Martha real, defined. Lehman imagined a monologue for Martha or George, I don’t really remember, with specific details about birth and death, time and place of death, physical appurtenances. Lehman did not approve of the child being imaginary. He could not conceive of the games people play with each other to survive, to manifest identities. He was very simple-minded, and his characters were mean or pretty or valiant or the villain to be dispatched to make the folks in the audience feel good about life. Lehman also thought the play should be altered—so Mike told me—to make it clear that Martha and Nick went upstairs to play whist or to look at her record collection. There was to be no attempt at sex, albeit a failed one, because that could make them unlikeable. Unlikeable! He optioned my play and thinks the characters are so black and white as to be likeable or valiant or degraded. I don’t think he understood shading at all. Lehman never believed that George and Martha actually loved each other, that this battle they construct—nightly, daily, always—is an attempt at intercourse, consummation, understanding. Life, you know, is terribly brutal, and as Tennessee told you, what has reality really ever done for any of us?”

SELDES: “One of my favorite questions.”

ALBEE: “I retreated from what life or reality had decided was mine at a very young age, and in all of my plays, you see the attempts made by people to gain an identity, or a better one, or a new one. Through religion, through sex, through fabrication. Really, through any means necessary.”

[During this statement, Marian had gone over to a table and picked up some papers.}

SELDES: “Edward, may I read this aloud?”

ALBEE: “Yes.”

SELDES: “I stood by for Irene Worth during Tiny Alice, and the joke was that I would likely never go on for her, because nothing stopped Irene. However, her throat began to give her trouble, and I was called, late one afternoon, while I was reading for another play, that I was needed. That was the word. ‘Miss Seldes, you are needed this evening.’ I asked so many questions about that play. I asked John Gielgud…”

ALBEE: “…as if he would know…”

SELDES: ‘…now, Edward. I asked Alan [Schneider, the play’s director], and he told me it was all in the text…”

ALBEE: “…smart man.”

SELDES; “But I screwed up my courage and went to Edward and I asked him—for me, for my benefit—what I should know about Alice, about the play, and this is what he told me.

‘Everyone in this play lives within a world that is both self-constructed and which has been constructed by others: clergy, law. We are told that there can be no order without systems that impose order, rules, control. The human spirit is creative and obstinate and hungry, however, and the human spirit will spin something for itself within a school or a church or an office. Or an affair. Or an evening. You craft for your Alice the life you think she needs, that you need.’

“Isn’t that wonderful?”

ALBEE: “I wish I hadn’t been so dismissive.”

SELDES: “Do you think that was dismissive?”

ALBEE: “Yes. I really didn’t want to discuss the play or the part, but I admired you, I liked you. I now love you. But I liked you then, and I felt I had to give you something, and you took it, and you used it, and you were wonderful. Alan was right, you know. It’s in the text. I have already written what I believe. Now it’s up to you to bring what you believe. This brings me back to Ernest Lehman, who wanted everything nailed down, described, clear. A summing up. It reminds me of those pitches to movie studios. Nut-shell it, they’ll say, and you have a minute to describe what something is about. Nothing of any worth at all can be summed up and put in a nutshell. Even John [Gielgud] wanted things nailed down. John was quite brilliant in Tiny Alice, even as he claimed he had no understanding of the play. But John is the type of actor—the type of professional—who adheres to the text, so he played what I wrote. Now, you can hate the play—many do—but John played it as written. Beautifully. Irene [Worth] brought so much more to it, because of her adventurous nature, and also, and this is just my theory, because she rose from Hattie from Nebraska to become this alluring creation, so creamy and beautiful and somehow ‘foreign.’ Irene understood fabrication. What did Tennessee call her?

JAMES: “The Goddess of Re-Invention, among other things.”

ALBEE: “Precisely. She made the world she wanted, with no malice or deception. Irene knew what she was doing. No one will ever play Alice as well as Irene, because I don’t think we create such intelligent actresses any longer. I don’t think we value the qualities that Irene possessed, even as we nostalgically pine for them.”

SELDES: “Really?”

ALBEE: “Yes. Talent—or to be more precise, brilliance—is very rare. I have had many good actresses, capable actresses, who have played Martha, but no one has come close to what Uta [Hagen] did with that part. How many Utas can the world produce? Uta was so fierce in her application of her talent and intelligence that she expanded what I had written. No one else has done that. I don’t think they can. Myra [Carter] in Three Tall Women is another example. No one will exemplify that woman as well as she did, and I say that with Marian in the room. Marian took over her part, and she was remarkable, but she was not Myra.”

SELDES: “I would be the first to admit to that.”

ALBEE: “But you were wonderful. You brought so much to it, but there is skimming across a part—like a skater on the ice—and there is breaking through the ice, falling to the depths, and then rising from that depth, surviving, and sharing. Uta and Myra and Irene could do that. Ironically, Arthur Hill was quite good as George, but not brilliant. There wasn’t as much depth to Arthur’s George, and now it is the Georges who are claiming the great praise and prizes when that play is revived. Ben Gazzara and Bill Irwin were far superior, in my mind, to Arthur Hill. They expanded what I wrote. They took it into some imaginary wood and built something with it, and then brought it to the stage, and left some of us in wonder.”

SELDES: “That’s beautiful.”

ALBEE: “I’m tired of people—critics, audiences, actors—trying to define, in a small way, what a play is. What the theatre is. What life is. I think it’s all vast. I think there is more mystery than we can realize. I want to confront people with this mystery. I want them to question where they stand in this mystery. I want them to admit to their inventions. I want them to revise their identities. I want them to look into re-invention. I know this may not be comfortable, but I happen to think it’s essential.”

The link to the event, in 2008, at the NYPL: https://www.nypl.org/audiovideo/edward-albee-conversation-marian-seldes

TO BE CONTINUED.