DIANE ARBUS, HER VISION, LIFE, AND DEATH

Adapted from DIANE ARBUS by Patricia Bosworth (Knopf, 1984)

AS A TEEN-AGER, DIANE Arbus used to stand on the window ledge of her parents' New York apartment in the San Remo, high above Central Park West. She would stand there on the ledge for as long as she could, gazing out at the trees and skyscrapers in the distance, until her mother pulled her back inside. Years later, Diane would say: ''I wanted to see if I could do it.'' And she would add: ''I didn't inherit my kingdom for a long time.''

Ultimately she discovered her kingdom with her camera. Her dream was to photograph everybody in the world, and by the end of the 1960's she was a legend in magazines, with edgy, transcendental photographs of peace marches, art openings, circuses and portraits of billionaire H. L. Hunt, Gloria Vanderbilt's baby, Coretta Scott King. She defined some of this work as ''funk and news.'' Her more personal projects (for which she won two Guggenheim Fellowships) were mysterious. In them she explored the eerie visual ambiguity of twins and triplets, the distinctions - and the connections - between bag ladies and wealthy matrons. Her complex feelings about her subject matter, her terror and fascination, were often reflected in her pictures. She thought of photography as an adventure, an event that required courage and tenacity. Her camera was also, as she said, her protection, her shield.

''A photograph is a secret about a secret,'' she said. ''The more it tells you, the less you know.'' This idea seemed to reverberate in her unsettling images of freaks and eccentrics, pictures that were beginning to be heralded in the art world when Diane Arbus killed herself in l971.

A year after her death, the Venice Biennale exhibited 10 huge blowups of her human oddities (midgets, transvestites, nudists) that were ''the overwhelming sensation of the American Pavilion,'' wrote Hilton Kramer, the art critic. Soon afterward, a large retrospective of her work opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and was both damned for its voyeurism and praised for its compassion. Crowds pushed in to see such Arbus portraits as ''A Jewish Giant at Home With His Parents,'' ''A Young Man in Curlers,'' ''Girl With Cigar in Washington Square.'' The show's themes - sexual role-playing and human isolation - seemed to sum up feelings that had surfaced in the 1960's and had flowed into the early 1970's.

A traveling exhibit featuring 79 of her pictures from Esquire and Harpers Bazaar is at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts through June 24; it will later be at the University of Kentucky Art Museum in Lexington, the California State University art museum in Long Beach and several other museums. Her works, like those of Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston, are now collected as art. Arbus prints have grown in value. A rare portfolio printed by herself and containing 11 of her most famous images was recently auctioned at Sotheby's for $42,900. A single Arbus, ''The Boy With Toy Hand Grenade,'' was priced not long ago at $8,000. The prints are strictly controlled by the Arbus estate and relatively few are on the market. The estate also has a policy of not giving publications reproduction rights to the pictures unless it has control over the accompanying text.

Her importance has extended beyond photographic circles. Lucas Samaris, the artist, has extolled her influence. Stanley Kubrick, the film maker, used her image of twins over and over again in his horror movie ''The Shining.'' Among many people, the phrase ''an Arbus face'' is synonymous with expressions of anguish, kinkiness and, in the words of Sanford Schwartz, the critic, a kind of ''creepy intimacy.''

DIANE ARBUS WAS BORN IN New York City on March 14, 1923. Her mother, the beautiful Gertrude Russek Nemerov, named her after the sublimely romantic heroine of the play ''Seventh Heaven,'' a role that was to be played four years later in the movies by Janet Gaynor. (With certain people, Diane insisted she be addressed as ''Dee-ann,'' but she answered to ''Dy-ann'' as well.) Diane's father, David Nemerov, ran Russeks Fifth Avenue, the family's fashionable fur and ladies' clothing store. A retailing innovator, he introduced the fur cardigan and tinted furs. He also pioneered the use of photographs, in place of illustrations, in newspaper advertisements.

The Nemerovs lived very well in big, lavish apartments with many servants. All three of the children were to become involved in the arts. Early on, Diane showed a talent for painting. Her younger sister, Renee, was to became a sculptor. Her older brother, Howard, is today one of America's most distinguished poets. He remembers that whenever he and Diane played in the park sandbox, they were forbidden by their nannies to take off their white gloves. Diane felt pampered, but isolated. For years, like many imaginative children of the time, she was terrified that the Lindbergh kidnapper would descend on her. Being afraid gave her pleasure, and much later she remembered that she loved to stay in her pitch-black bedroom at night waiting for monsters to come and tickle her to death.

Diane attended the Fieldston School in the Riverdale section of the Bronx from the seventh through the 12th grades, and for one year Howard was there at the same time. Teachers said they were the most gifted brother and sister who had ever attended that institution. They hated being compared. Later, when Howard became a poet and Diane a photographer, they never discussed their work with each other. In fact, they rarely told anyone of the other's existence. ''And I, for one, have no theories as to how or why we became what we became,'' Howard says now.

Diane and her classmates were taken to visit a settlement house on the lower West Side, an immaculate building set in a decaying slum. The students were forbidden to speak to the derelicts who lounged in the doorways. Diane longed to talk to these strange people, to find out their thoughts. Years later, she said, ''One of the things I suffered from as a kid was I never felt adversity. I felt confirmed in a sense of unreality which I could feel as unreality, and the sense of being immune was, ludicrous as it seems, a painful one.'' As far as she was concerned ''the world seemed to belong to the world. I could learn things but they never seemed to be my own experience.''

To counteract this, she and a friend, Phyllis Carton, created little adventures for themselves. They would ride all over the subway system observing the strange passengers - an albino messenger boy, a little girl with a purple birthmark. These were visual and sensual experiences for Diane, and they frightened and pleased her.

Periodically during vacations she worked at Russeks in the stock room. She said later, ''I absolutely hated furs; I found the family fortune humiliating.'' But as a teen-ager she suffered in silence. Working in the Russeks advertising department as a paste-up boy was Allan Arbus, a slender, handsome, curly-haired 19-year-old who was going to City College at night. He wanted to become an actor. Diane took one look at him and he took one look at her and, according to Ben Lichtenstein, a Russeks executive, ''they fell madly in love.'' Diane liked to say that Allan was the most beautiful man she had ever seen and that their romance was like Romeo and Juliet.

They continued to see each other - in spite of parental disapproval - during Diane's years at Fieldston. Her friends knew of Allan's existence, but she never took him to school. Secrecy was always important to her - as it was to Allan. They were a scrupulously private couple.

THERE WERE A LOT OF BOYS in love with her,'' recalls the family counselor Eda J. LeShan, who was a classmate. The screenwriter Stewart Stern, another classmate, says, ''She was irresistible. I used to stand outside her apartment looking up at her window hoping I'd catch a glimpse of her. When you were with her she made you feel like you were the only person in the world.'' And Alexander Eliot, a good friend who met her at this time, says, ''Her physical presence was so extraordinary she startled me, took my breath away. It was like coming upon a deer in a forest.''

She was doing exceedingly well in school. Friends remember her bold paintings, the confrontational way she sketched the naked models relaxing and smoking in life-study class. She also made bizarre little pencil sketches, caricatures of people she saw on the street. She helped Stewart Stern complete a mural in the school dining room. Her adviser and art teacher, Victor D'Amico, encouraged her to think seriously about becoming a painter after she graduated. ''But Diane was scared stiff of her talent,'' says her girlhood friend, now Phyllis Carton Contini. ''It set her so apart.''

So when she fell in love with Allan Arbus, she stopped dreaming of being, in her phrase, ''a great sad artist.'' She decided to get married right after she graduated. ''Falling in love with Allan had made Diane feel very grown up,'' Phyllis Contini says. ''Marriage would mean a huge life experience. She was preoccupied with anything physical - any physical sensation that made her believe she was alive. Her menstrual cycle fascinated her. We discussed the mysteries of conception; she thought childbirth must be the most extraordinary experience in the world.''

By early 1941, the Nemerovs, exhausted from resisting, finally consented to the marriage. As a wedding present, Gertrude Nemerov gave Diane a five-year supply of clothes from Russeks and the use of a ladies' maid for a year.

After Pearl Harbor, Allan Arbus joined the Army Signal Corps and attended photography school at Fort Monmouth, N.J. Diane moved near him to a one-room apartment in Red Bank. She set up a darkroom in their bathroom, and every night Allan would come back from school and teach her what he had learned. She started snapping pictures all the time. She never talked about why she was so drawn to photography, but she did say once that what intrigued her about the camera was that ''it's recalcitrant. It's determined to do one thing and you want it to do something else.'' In 1944, Allan went to Burma with a photography unit, and when he came back after the war, he and Diane became fashion photographers.

They got their first account in l946, photographing furs for Russeks. For the next decade, they worked constantly for the store and for Glamour and Vogue, even though neither of them had any interest in fashion; it seemed too frivolous, too ephemeral. Diane in particular hated the business, hated the stiff new clothes the models wore. She herself went barefoot most of the time, carried a brown paper bag instead of a purse and would wear a shirtwaist dress over and over until it developed ''character.'' Eventually, she stopped taking fashion photographs and worked instead as Allan's assistant, ''styling'' the shots for him. She was very good at this, and they became even more successful as a team. In 1955, one of their Vogue pictures, of a father reading the newspaper to his son, was chosen by Edward Steichen to be in the famous ''Family of Man'' photographic exhibit.

She and Allan really loved each other, Diane said. They would never stop loving each other. She believed implicitly in romantic love - in passion and a quickening of the blood. But she couldn't reconcile the perpetual conflict in herself between love and lust, between need and fear. Sex was very important to her. She bragged that she and Allan ''made love all the time.'' She had a growing curiosity about what other married people did in bed, and she had begun to ask friends intimate questions about their sex lives. She once confided that she envied a girlfriend who'd been raped. She wanted to have that punishing, degrading experience, too. She could almost imagine it was like a murder - the murder of a woman's nature and body - though the woman lived to tell the tale.

To combat frequent depressions, Diane took pictures on her own. She had no particular focus or goal, just a vague feeling that she wanted to photograph worlds hidden from public view. For a while, she took pictures of people's bathrooms. She was fascinated by the rich gardens flowering in some shower stalls, in the stacks of old magazines and newspapers piled near certain toilets, the endless array of perfumes, soaps, creams and tranquilizers on so many shelves. ''A person's bathroom is like a biography,'' Diane said. She was too shy to ask strangers to pose, so instead she took pictures of friends. She photographed, off and on, a great many children - enraptured Puerto Rican kids watching a puppet show in Spanish Harlem; a tiny, seemingly deformed boy and girl laughing into her camera (this picture ended up as an Evergreen magazine cover in 1963). Then there were endless candids of her two daughters, Doon and Amy. John Szarkowski, director of the department of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, says, ''Her most frequent subject in fact was children - perhaps because their individuality is purer, less skillfully concealed, closer to the surface.''

In 1957, Diane inexplicably burst into tears at a dinner party when a friend asked her to describe her routine during a fashion shoot. She, who never cried, who hated crying, began to sob as she ticked off her duties: brush the model's hair, pin up the dress, arrange the props just so, turn on the fan. She hadn't had much practice crying, and the sobs seemed to have trouble coming from her throat. They were ugly, constricted cries and Allan couldn't stand listening to them. Then and there he decided she would never again style the shots for a Diane and Allan Arbus fashion layout, and she never did.

From this point on, her own photography became her main concern. But there were adjustments to make, since she felt torn between her responsibilities as a wife and mother and her deep need to photograph. She often made both her daughters accompany her when she took pictures in the streets. Allan meanwhile, still determined to be an actor, enrolled in mime class. Eventually, although they remained close friends and he would always be her biggest champion (''He was my first teacher,'' she often said.), the Arbuses drifted apart. In time, while Allan continued living at their studio on Washington Place, Diane moved with her girls to a little house on Charles Street, and people and events more closely linked to documentary photography began taking over her life.

She wanted to get away from slick, romantic fashion images; she was responding to the work of her contemporaries Louis Faurer and Robert Frank, who scorned elegance and were experimenting with exaggerated scale and shadows, outrageous cropping and out- of-focus imagery. She responded to the demonic violence in Weegee's crude pictures, too. Weegee was a fast-talking, cigar-smoking press photographer. But Diane was most impressed with Lisette Model's images of grotesques which had been documented with almost clinical detachment. These pictures of poverty and old age were 16- by 20-inch prints of beggars, drunks and rich people blown up to such heroic proportions you could almost feel their existence. Model called them ''extremes.''

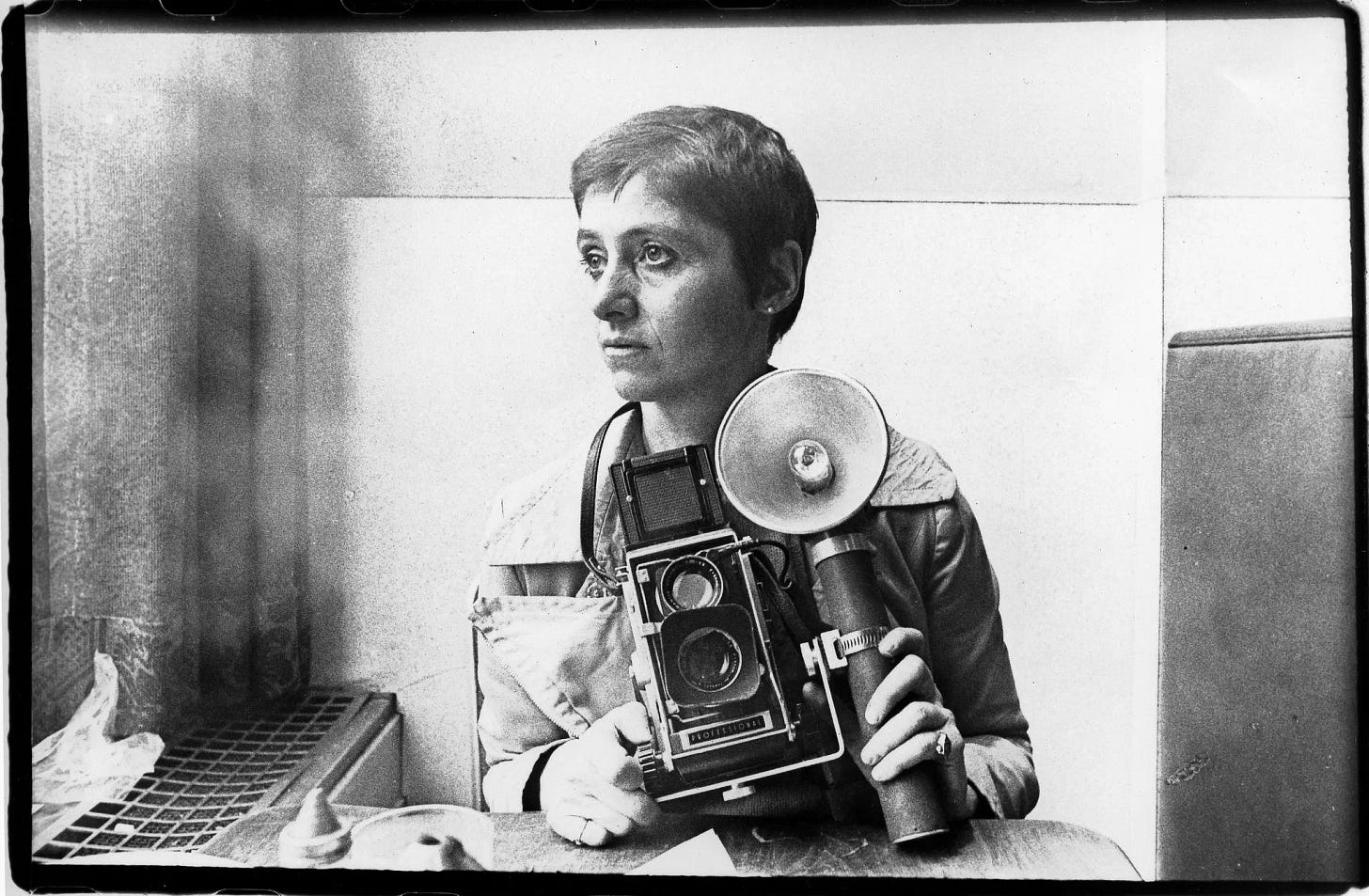

The photographer Lisette Model, born in Vienna in 1906, was said to use the camera with her entire body. Benedict J. Fernandez, head of the photography department at the New School for Social Research, called her eyes ''the most instinctive eyes in photography.'' Model's first pictures - massive portraits of French gamblers and the idle rich taken on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice - established her reputation when they were published in the New York newspaper P.M. in 1940 under the title ''Why France Fell.'' She had come to New York in 1937 and was turned into something of a celebrity when her pictures were shown at the Museum of Modern Art, and were praised by the photographers Ansel Adams and Walker Evans and by the critic Beaumont Newhall. By the late 1950's she was giving lectures at the New School, and Diane Arbus went to study with her. Model remembered Diane as extremely nervous, a woman in her mid-30's who still looked like a little girl.

Model taught that photography has extended our vision, but in ways we still cannot understand. Photography was first viewed as a superstition, she would say, but it is now an addictive craving. There is a big difference between what the eye sees and what the camera sees. The transformation between the third dimension and second dimension can make or break a picture. She talked a lot about technique, the psychological importance of light and the visceral exchange that was necessary between subject and photographer. But in the end, she told her students, they must forget everything she told them. ''Photography is about creating a picture,'' she said.

One of Model's first assignments to Diane and the others was to photograph a face ''like a Picasso.'' She urged her students to intensify their compulsion to take pictures by wandering through the streets of New York carrying cameras without film. ''Don't shoot until the subject hits you in the pit of the stomach,'' the photographer Berenice Abbott quotes her as saying.

The first extended conversation between Diane and Model took place on a field trip to the Lower East Side. Diane had her two daughters along, trailing behind as she kept lifting her camera to her eye and putting it down. According to Model she was very pale. Finally she said, ''I can't photograph.'' Model asked her why. Diane said she'd have to think about it. The following day she came back with an answer. ''I can't photograph because what I want to photograph is evil,'' she said.

''Evil or not, if you don't photograph what you are compelled to photograph, then you'll never photograph,'' Model answered. She understood that certain pictures had to be taken in order for Diane to relieve her mind of the images that were haunting it. She said later that she had tried to reach Diane where her deepest anxiety lay, the anxiety Diane thought was evil. ''And I pushed it out,'' Model said.

Years later, Doon wrote: ''I think what Mother wanted to photograph was not evil but forbidden subject matter and Lisette gave her license to do that.''

Diane took the D train to Coney Island. She discovered a tenement off Stillwell Avenue. She marched inside and discovered it was actually a hotel full of disoriented old people and a barking dog. She spent hours photographing there. ''If I ever went away for a weekend this is where I'd go,'' she said. She returned to Coney Island again and again. She photographed the wax museum, Puerto Rican mothers, tattooed people. She kept asking why people get tattooed. For decoration? To hide scars? On a dare? The secret ritual of it intrigued her since it was a combination of traditional art, physical pain and sensuality. The hardest thing in all this was trying to overcome her shyness, the nauseating feeling whenever she had to ask someone to pose. She'd stop a man or woman who intrigued her by exclaiming, ''Oh, you look terrific! I'd like to photograph you,'' and the person would usually hem and haw and then consent, because Diane seemed so gentle and unthreatening. ''I was terrified most of the time,'' she said. But terror, as always, aroused her and made her feel; it shattered her listlessness, her depression.

Like Model, she now believed that picture-taking is a profound experience. ''The very process of posing requires a person to step out of himself as if he were an object,'' she liked to say. ''He is no longer a self but he is still trying to look like the self he imagines himself to be. It's impossible to get out of your skin and into somebody else's and that's what photography is all about.''

After a while, she realized that people paid attention to her because of the camera in her hand; they treated her with respect and kept their distance - gave her space. Eventually, she wore a camera at all times. ''I never take it off,'' she would say.

She began to prowl the city at all hours, striking up conversations with any outcasts she happened to encounter. She wasn't afraid of New York at 2 A.M. She seemed to be more alive in the dark as she traveled by herself on the subway, laden down with her cameras. The trains pounded in and out of the dark tunnels, headlights shining like eyes. The stations were deep, empty, smelly - ''like the pits of hell,'' she said. She saw hunchbacks, paraplegics, exhausted whores, boys with harelips, pimply teen-age girls. She was sure the ladies in ratty fur coats were cashiers.

She considered photographing the men who lived in the bowels of Grand Central Terminal, bums who wrapped their feet in old newspapers to keep warm. She befriended a bag lady, a woman who was a fixture in the corridor connecting the Lexington Avenue subway to the Times Square shuttle. The bag lady would lie in a corner day and night, hardly moving. The rumble of the trains in the distance was like the sound of the sea in her ear; gradually, she told Diane, it was going to rise up and envelop her completely. She spent a lot of time at Hubert's Freak Museum, which had been operating for more than 25 years at Broadway and 42d Street. She always visited Professor Heckler, who ran the flea- circus concession there. Diane liked to sit with him while he fed his fleas. He would roll up his sleeves, pick the fleas with tweezers from their mother-of- pearl boxes, drop them on his forearm and let them eat their lunch while he read the newspaper. Diane would remain in Hubert's for hours, so scared her heart would pound and sweat would pop out on her brow. Then she would conquer her fear and scrutinize the fat lady's waddle, the armless man's dexterity as he lit a cigarette from the match he held between his toes. She would come back day after day, and once she felt that the freaks trusted her, she asked them to pose.

In the late summer of 1959, Diane took her portfolio to Esquire. The writer Thomas B. Morgan had suggested that she show her photographs to Harold Hayes, the Esquire articles editor who went on to be editor in chief. Hayes recalls being ''bowled over by Diane's images - a dwarf in a clown's costume, television sets, movie marquees, Dracula. Her vision, her subject matter, her snapshot style were perfect for Esquire, perfect for the times; she stripped away everything to the thing itself. It seemed apocalyptic.''

He showed the portfolio to Robert Benton who was then Esquire's art director (long before he went on to win two Oscars for writing and directing ''Kramer vs. Kramer''), and Benton agreed. ''Diane knew the importance of subject matter. And she had a special ability to seek out peculiar subject matter and then confront it with her camera. It was like something I'd never seen before. She seemed to be able to suggest how it felt to be a midget or a transvestite. She got close to these people - yet she remained detached.''

Hayes, Benton and Clay Felker, the features editor, had come up with the idea of devoting an entire issue of Esquire to New York. Hayes told Diane he wanted her to do a photographic essay on the night life of the city, emphasizing events, people and places nobody knew about.

Diane was intrigued. ''Let me waste some film!'' she exclaimed to Benton, adding that she planned to photograph River House, drug addicts, Welfare Island, Roseland and the newsroom of The Bowery News ''for starters.'' She went on to tell him that she'd been ''peering into Rolls- Royces, skulking around the Plaza Hotel.'' She'd also thumbed through the Yellow Pages under ''clubs'' (Harold Hayes wanted something ''respectable'' like the Colony Club and the Union League), and she'd found one called ''the Tough Club'' and another, ''Ourselves Inc.'' She reminded Benton that Mathew Brady had once photographed the Daughters of the American Revolution and that the results had been ''formidable.'' In a note scribbled to Benton she asked for ''permissions both posh and sordid . . . . I can only get photographs by photographing. I will go anywhere.''

Diane began the Esquire assignment by visiting the morgue at Bellevue, a cavernous building on the East River near 27th Street and a place of dank tiles and refrigerated corpses. In the autopsy room, the air was heavy with the smell of decomposing flesh, of viscera open for examination. Diane got to know some of the forensic doctors and she was allowed to photograph there. She began to collect information about death and dying. The terminology, particularly of suicides, fascinated her: hangings, suffocations, cut throats, bodies dragged from the bottom of the Hudson river.

She roamed in and out of Manhattan's flophouses, brothels and seedy hotels, the little parks on Abingdon and Union Squares, the parks near the Brooklyn Bridge and Chinatown. Soon, her address books were filled with an incongruous collection of names: ''Detective Wanderer - West Side homicide . . . subway brakeman, Kass Pollack . . . Vincent Lopez, band leader . . . Flora Knapp Dickinson, D.A.R. . . . .'' ''I love it, I feel like an explorer,'' she said to Seymour Krim, the writer. ''I own New York!'' she exulted to her sister, Renee. She placed a blackboard by her bed with a list of places and people she wanted to photograph: ''Pet crematorium, New York Doll Hospital, Horse Show, opening of the Met, Manhattan Hospital for the Insane, condemned hotel, Anne Bancroft in 'The Miracle Worker'.''

From anxiety, she shot hundreds of rolls of film on the Esquire assignment. Robert Benton and Harold Hayes were so excited by the raw images she kept bringing in that they considered illustrating the entire New York issue with Arbus pictures. ''I foolishly decided against it,'' Hayes says now. ''The pictures were such an indictment.''

He and Benton finally chose six for the July 1960 issue - among them, Flora Knapp Dickinson of the D.A.R.; an unknown person in the morgue at Bellevue; a beautiful blonde, Mrs. Dagmar Patino, at the Grand Ball benefiting Boys Town of Italy, and Walter Gregory, an almost legendary Bowery character known as ''The Madman from Massachusetts.''

The four years following that first Esquire job were the most productive and energizing periods of Diane's life. As she struggled to come to grips with her themes, her style and her subject matter became more extreme (transvestites, nudists, a giant). Eventually she stopped using the 35 millimeter format, switched to the square 2 1/4-inch format using a Rolleiflex camera and later alternated between it and a 35 millimeter Mamiya with flash. This was a crucial change for her. Her subjects took on a stronger life, and the illumination of the flash stripped away artifice to reveal a psychological truth. The film's square format, as she used it, seemed to imprison the subjects.

She had many magazine assignments, including several from Show, although Show's art director, Henry Wolf, wasn't that pleased by her crude, abrasive work. ''I couldn't use some of the pictures she shot for Gloria Steinem's story on movie theaters in Ohio - they weren't that good - and I refused to publish her portrait of the human pincushion, even though she kept urging me to.'' Wolf, a cultivated gentleman who later was a partner in a successful advertising agency before becoming a photographer himself, confesses, ''Diane always made me feel guilty for enjoying myself. Once I ran into her on a beautiful Saturday morning all decked out in her cameras. 'What are you doing on such a gorgeous day?' I asked. 'Trying to find some unhappy people,' she answered. Well, I couldn't relate to that !''

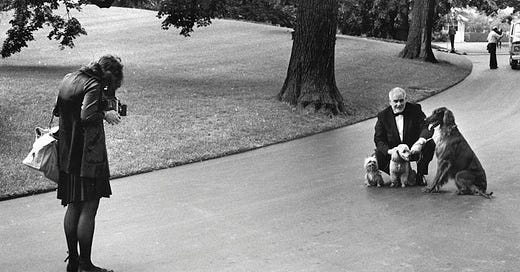

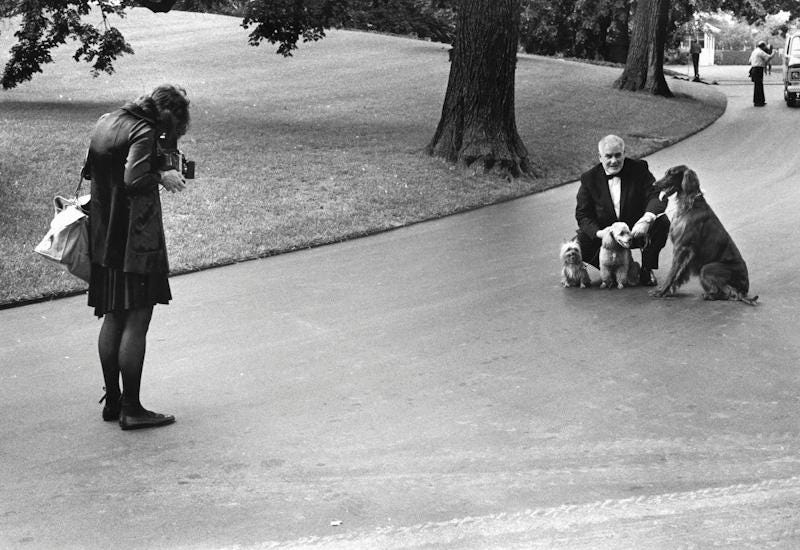

By the mid-1960's, Diane had become a familiar figure to almost every working photographer in New York City. She was seen at art openings, at happenings, at the Judson Memorial Church, at an Ethel Scull party held at Nathan's, at a Tiger Morse fashion show, at the Henry Hudson Health Club where models stoned on pot showed off lingerie, then fell into the pool. ''Diane was at every spectacle, every parade,'' the photograher Bob Adelman says, ''right up to the Gay Liberation Day march of 1970.''

Adelman, who eloquently documented the civil-rights movement in the pages of Look magazine, recalls seeing Diane at ''most of the protests against the Vietnam War. But she would never plunge into the crowd like the rest of us. We were all going for a sense of immediacy, of grabbing on to the entire vista - we wanted to record the action. But Diane hung back on the fringes. She'd pick out one face, like the pimply guy with the flag or the man with his hat over his heart.''

On assignment, in competition with other (mostly male) photographers, Arbus could turn cold and aggressive. Sometimes at an art opening or press conference she would hop about here and there, click-clicking away at people until they ran through their repertoire of public faces and stood exposed, blinking under the glare of her flash. ''She used to drive people crazy at parties,'' photographer Frederick Eberstadt says. ''She'd behave like the first paparazzi. She didn't talk much but she'd swoop like a vulture on somebody and then blaze away. And she would wait outside a place for hours in any kind of weather to get the kind of picture she wanted.''

Everyone who knew her then came away with a different impression of her. ''A huntress,'' Walker Evans said. ''Elegance, high intelligence and such amtition,'' John Szarkowski says. The writer Gay Talese recalls, ''She was lovely, but she always seemed to be in another time. She had a worn quality about her, an ashen quality - she was remarkably gray, out of focus - and sometimes there was a sense of dust about her - as if she was uncared for. Her skin looked older than it should have. But God, she had a beautiful face! Gorgeous. Particularly in profile. And deep-set, strange, watchful eyes.'' Her friend Marvin Israel, the painter and art director, wrote in an article: ''Diane loved being naughty. Much of what she did as a photographer came from that kind of delight.''

Peter Crookston, a London editor, once listened as she told a story, complete with gestures and accents, about a photo assignment. The subject had been a celebrated lawyer. She'd arrived at his office and found a British reporter already there interviewing him - a very pretty, very ambitious journalist who, Diane sensed, wanted to seduce the man, ''because this lawyer was rather sexy and powerful, too.'' Diane decided ''for kicks'' to seduce him first - and for the next hour she exerted her fey charm on the man while blinding him with her flash. He got sweatier and more excited and finally the British journalist left, and Diane said she'd felt sorry for her because ''she didn't have the patience I had. I hung in there.''

Sex would become the quickest, most primitive way for Diane to begin connecting with another human being. It was almost as if she were determined to explore with her own body and waking mind every nightmare, every fantasy she might have repressed deep in her subconscious.

In 1965, three of Diane's earliest pictures were included in a show at New York's Museum of Modern Art. The public's reaction was extreme. Yeu- bun Yee, then the photo department's librarian, came in early every morning to wipe the spit from the Arbus portraits. Nevertheless, two years later, she shared another photo exhibition at the museum with Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, a show called ''New Documents.'' This was crucial in shaping the social-documentary style of the 1970's, and most of the comments it generated, both praise and censure, focused on Arbus's portraits of nudists, midgets and transvestites.

That same fall, in 1967, Diane was invited to attend ''idea'' meetings at New York magazine which was about to revolutionize the weekly ''city magazine'' format. She joined contributing editors Gloria Steinem, Barbara Goldsmith and Tom Wolfe in editor Clay Felker's cluttered little office.

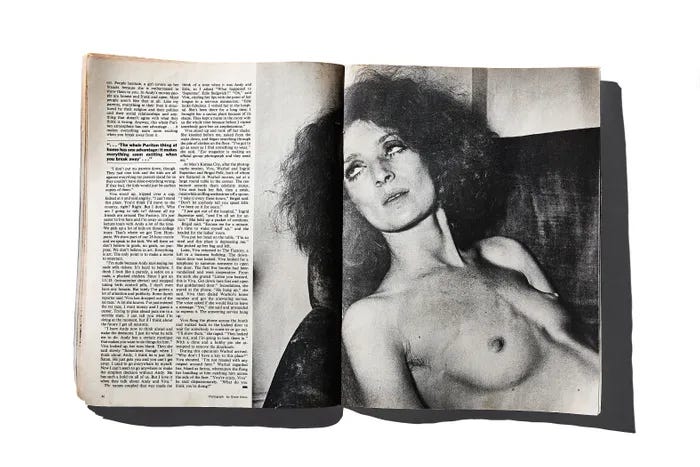

Diane understood Felker. ''He has a photographer's mentality,'' she once commented. ''He'll stop at nothing to get the image - he'll pay any price.'' At one meeting there was a great deal of discussion about Andy Warhol, who seemed to the group to be setting the tone of the 1960's. Warhol had been promoting an exceptionally beautiful actress named Viva. In his most recent movie, ''Lonesome Cowboys,'' she could be observed nude and talking nonstop while participating in an orgy. Felker decided that Diane should photograph Viva.

Viva's memory of their encounter is a bitter one: ''Diane rang the doorbell. It was pretty early. I'd been asleep on the couch. I was naked so I wrapped a sheet around me and let Diane in and then I started putting mascara on. I was about to get into some clothes when Diane told me 'don't bother - you seem more relaxed that way - anyway, I'm just going to do a head shot.' I believed her. She had me lie on the couch naked and roll my eyes up to the ceiling which I did. Those photographs were totally faked. I looked stoned but I wasn't stoned, I was cold sober. There was nothing natural about those pictures, nothing spontaneous. They were planned and manipulated. Diane Arbus lied, cheated and victimized me. She said she was just going to take head shots. I trusted her because she acted like a martyr, a little saint, about the the whole thing. Jesus! Underneath she was just as ambitious as we all were to make it - to get ahead. I remember right afterwards I phoned Dick Avedon because he'd just done some gorgeous shots of me for Vogue. I told him 'Diane Arbus has taken pictures of me for New York magazine,' and he groaned, 'Oh My God, no! You shouldn't have let her.' And Andy told me the same thing. After the fact. I'd never seen her work. I didn't know an Arbus from a Philippe Halsmann.''

The photographs of Viva (which accompanied an article by Barbara Goldsmith) appeared in New York magazine in April 1968, and were absolutely merciless. Out of the dozens of contact prints, Felker and Milton Glaser, the design director, chose two. One was a jarring grainy closeup in which Viva appears dazed and drugged, eyes rolled back into her sockets. In the other portrait Viva can be seen naked and roaring with laughter on a sheet-draped couch. There is a raunchy casualness about the pose; she appears pleased with herself right down to the soles of her dirty feet. The qualities that are distressing and alienating in some of Diane's work - the severity, the seeming disregard for the subject - are very apparent here. When Diana Vreeland, then the editor of Vogue, saw the pictures she screamed and canceled the rest of Viva's bookings. The Viva pictures created such a furor along Madison Avenue that New York magazine seemed about to lose all its advertisers.

Today, Clay Felker winces when he recalls the incident. ''I made a terrible mistake publishing them,'' he says. ''They were too strong - they offended too many people.''

Diane wrote to an English friend, ''It is a cause celebre. Much mail. Canceled subscriptions, pro and con phone calls and even a threatened lawsuit'' (from Viva which was ultimately dropped).

The writer Thomas Morgan thinks the Viva pictures were ''watershed pictures. They broke down barriers between public and private lives. They were painful photographs to look at - that was what made them significant. You're reacting the way Diane reacted. That's why her images have such a startling effect - they invariably contain contradictory responses.''

In 1969, Allan Arbus divorced Diane and married Mariclare Costello, a young actress. Diane gave them a small reception, remarking later that she felt ''sad happy'' about the occasion. She said that Mariclare was a ''good friend'' of hers, and that the two of them ''hung out on the phone a lot.'' Not long after the wedding party, Allan closed his fashion studio, and he and his new wife moved to Hollywood to pursue their acting careers. (He would, among other things, play the psychiatrist Dr. Sidney Freedman in the M*A*S*H* television series.) Diane outwardly applauded the move. But she was frightened. She had depended on him emotionally since she was 14; throughout their long separation, they had remained close. Until recently, he had printed much of her work; now he would be 3,000 miles away.

Late that year, the sculptor Mary Frank and Diane discussed moving to Westbeth, the new artists' community that had just opened near the Hudson River docks. To outsiders, the massive gray stone buildings, a 13-story pile that once had been Bell Telephone Laboratories, might resemble ''a Swedish prison,'' but Mary thought Diane would be less lonely there. ''Everybody at Westbeth was creating wildly,'' says David Gillison, a photographer and painter who still lives there. ''Actors, painters, musicians, photographers - it was like living inside a big turbulent pot. There were all-night parties, consciousness sessions . . . People left their doors open . . .'' Diane moved to Westbeth in January of 1970 along with the choreographer Merce Cunningham, the poet Muriel Rukeyser and the documentary photographer Cosmos, who hadn't shaved since John F. Kennedy was assassinated. And for a while she seemed happy in her new duplex. It had a wonderful view of the river; she had space for her bicycle, her plants, her platform bed covered with furs.

But she was barely making enough money to pay the rent. For the next year she taught classes, she worked part time doing research for the Museum of Modern Art, she was assigned to cover Tricia Nixon's wedding for the London Sunday Times magazine, on her own she was photographing retardates. She had been sick twice with hepatitis. She was having increasingly severe depressions. She refused to take any tranquilizers, because she had discovered she had bad reactions to most drugs. She spent her free time phoning people - friends like Richard Avedon and Marvin Israel, Lisette Model, Allan in California, her mother in Florida.

By June 1971, she began complaining that her work wasn't giving her back anything any more and she was in a panic. She kept referring to her ''monumental blues.'' When Walker Evans suggested to his colleagues that she be his successor teaching photography at Yale, she said no.

On July 27, the telephone started ringing in Diane's apartment. One of her students called again and again, trying to confirm the fact that she would be conducting a symposium on photography he had organized for later in the week. Marvin Israel called several times, too, and he got no answer. On July 28, he went over to Westbeth.

He found Diane dead with her wrists slit, lying on her side in the empty bathtub. She was dressed in pants and shirt - her body was already in a state of decomposition, according to the coroner's report. On her desk, her journal was open to July 26, and across it was scrawled: ''The last supper.'' The New York medical examiner concluded that she had died of acute barbiturate poisoning.

Her funeral at the Frank Campbell Funeral Chapel at 81st Street and Madison Avenue was sparsely attended. Many of her friends were away for the summer; others weren't informed. Allan Arbus flew in from California with his wife. Diane's mother and daughters were there and so was Diane's brother, Howard Nemerov.

He gave the eulogy. It was short. Later, he wrote a poem about Diane which has been reprinted many times. It ends:

And now you've gone, Who would no longer play the grown-

ups' game Where, balanced on the ledge above

the dark, You go on running and you don't look

down, Nor ever jump because you fear to

fall.

(This piece appeared in the Magazine of the New York Times on Sunday, May 13, 1984.)