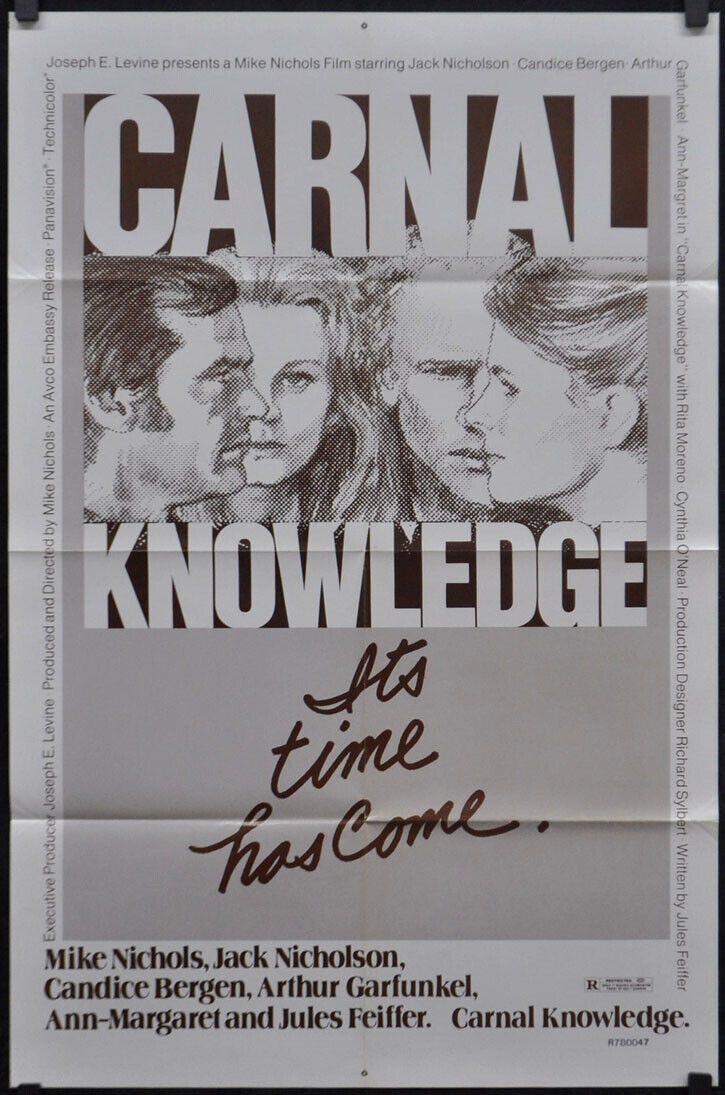

Via Esquire

By Geoffrey Wolff

November 1981

MEN I HUNG OUT with must have heard the far-off thunder years before, but by 1971, when Mike Nichols’s Carnal Knowledge was released, we couldn’t ignore the storm. Women were furious and in full cry—questioning (why should I? why shouldn’t I?), exhorting (be free, sisters; grow up, boys), complaining (about wages, physiology, The System, men), repudiating (the convention of marriage; the imperatives of motherhood, housekeeping, men).

A decade ago it was discomforting to watch Jack Nicholson play Jonathan, a prisoner of sex, a pussy hound treed by the game he chased. Viewed through the optic of the period’s sexual politics, his progressive decline into foolishness, sadness, and impotence invited a judgment upon him that felt oddly distanced, like the QED of a moral allegory in which the judge and witness—myself, really— failed to identify himself as an accomplice.

Ten years later, now, I settled in to watch Carnal Knowledge with a friend, preparing to judge Jonathan again. This time the movie bushwhacked me, hit me with a shock of recognition like a sockful of BBs behind the ear. It is not at all a movie meant to confirm generalized Woman’s worst suspicions of generalized Man. It’s about a particular American caste (privileged college graduates, professionals) at a particular time (from the end of World War II to the late Sixties). The proprietary idiocy of Jonathan and his Amherst roommate, Sandy (Art Garfunkel), is the consequence of a particular culture’s peculiar way of regarding sex and, more important, power.

The culture of the Fifties, like the culture of the Eighties, served the self above all masters—but more stridently (or innocently) then than now.

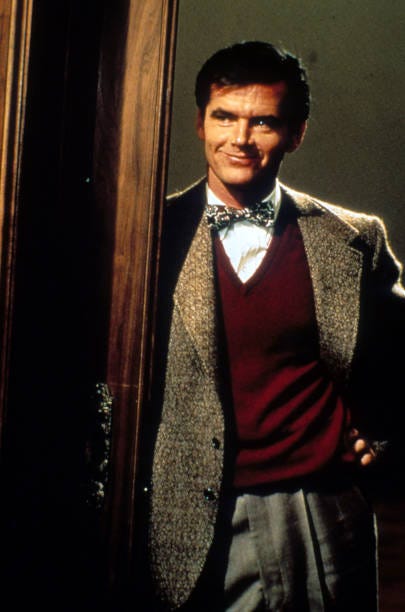

Jules Feiffer’s screenplay and Mike Nichols’s costumes and props make up a comprehensive inventory of a culture that peaked in the Fifties, of middle-class totems, taboos, manners, and purposes. Sandy’s and Jonathan’s saddle shoes, baggy flannels, tweed jackets, V-neck sweaters, and three-piece suits worn with narrow rep ties situate Carnal Knowledge in time. The movie is fixed in spirit (cool) by the chums’ droopy eyelids and smirky leers. Like everyone at college then, Sandy longs to lose his cherry, though sometimes he whines that an unspecified “they” excessively pressure him into getting laid. He is the roommate who wears pajamas, so he apprentices himself out to Jonathan, who sleeps bare-assed and who longs to lose his cherry.

To “get in,” to have had “it,” to take “it,” is their desideratum and entire preoccupation. Jonathan and Sandy talk of “nice” versus “hot,” “nice” versus “beautiful”; they ponder the ultimate epistemological conundrum: Which is better, to be loved by it or to “bang” it?

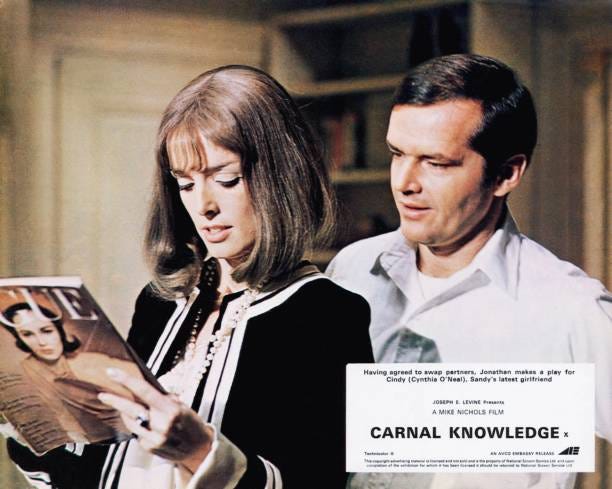

“It” is first seen at an Amherst-Smith mixer, embodied in Susan (Candice Bergen), encased in a wool plaid skirt and sweater. “I’m Getting Sentimental over You” plays; Jonathan smirks, advises Sandy to go after Susan, to throw her a line, to trade on his (bogus) unhappy childhood. Instead, Sandy and Susan uncomfortably discuss parties, why they hate them. The newlymets discuss masks and disguises, the “real me” and the “real you,” the usual. Sandy has a hunch he might score, as he of course tells Jonathan, who then decides he wants Susan. “She’s mine,” Sandy whines. “You gave her to me.”

Women are organs and ciphers, orifices merely, possessions (once possessed). Jonathan and Sandy are consumers competing for the only available piece of something, so it’s triangle time. Jonathan seduces Susan (which Sandy intuits later). He thinks his line snags her, tells her his father is a Communist (wooing her, a Republican, on the bohemian platform) and a lifelong failure (setting up a fallback on the pity front). “After I get set up as a lawyer,” he says to Susan, “what I’d really like to do is go into politics—public service.” Whatever. They do it under a blanket beneath the stars, and the noises they make sound like middle-sized animals with bad tummy aches. Afterward, freed from virginity, Jonathan rolls off her. He looks puzzled, just a bit disappointed, as though he had traveled a long way at great cost and discomfort, climbing a final range of snake-infested mountains to find spread in the valley at his feet . . . Bridgeport. He’s already a goner.

Jonathan tells Sandy that he’s scored but not with whom. It’s another attainment, evidence of power, the exercise of the will; it’s of a piece with Jonathan’s ambition to be a lawyer, Sandy’s to be a doctor. They neither torment themselves about the character of these choices nor fret about whether they will succeed. They move forward, taking ground; now Sandy must have what Jonathan has had. His campaign is inexorable, responsive only to the logic of his ambition. He moves from base to base, cranking up the stakes; a kiss today must be followed by two tomorrow. Feiffer and Nichols have the desperate comedy of that time tone-perfect: the glancing allusions to rubbers (“Do you have anything?”), to organic geography (here? there? where?), even to the escape hatch of a hand job after failed appeals to “friendship.”

I remember that determined dexterity; those prayers from the back seat for three hands, prayers that she’d fall asleep (better, pretend to fall asleep); the big-tit gestalt; the forlorn slapstick; the farcical war fought between us and them, as though we were intelligence agents behind the lines, speaking only in code. It encouraged in us boys sharp wits and dull vision, a preoccupation with the available rather than with the main chance. “I love you,” Sandy says. “Let’s do it.” Eventually Sandy scores, but not before Susan pleads with him: “How can it be fun if you know I don’t want it?”

Sandy is too busy with his hands to reply immediately, but when I first saw Carnal Knowledge ten years ago a friend answered for him: “You supply the pussy, let me worry about the fun.” Watching it this year with a friend about Sandy’s age, I asked him what he thought of Susan’s question. We are all hedged up now, checking the temperature on the far side of the liberationist fires, looking around the room for “them” or their representatives before we speak: “Sensible question from the woman,” said my friend, grinning a secret agent’s grin. Bullshit artist.

“Bullshit artist!” is the movie’s chorus cry, what Jonathan and Sandy call each other. Tracking “it” is dark and lonely work, but a man has to do it, and a man doing it can’t afford to be softened by the truth. Truth will finally soften Jonathan, though, in the most awful way. The first truth to reach him is that Susan never cared about his line, his personality, or his mind. She used him; he was what they now call a sex object, a humanlike vibrator.

A few scenes later Jonathan begins to utter the movie’s signature line, a litany of self-pity that is more an expression of Fifties misogyny than a generalizing sentiment of the late Sixties and early Seventies: women are “ball busters,” women “today” (which means whatever time he chances to make the observation) “are better hung than the men.”

After college, Jonathan, a lawyer, makes plenty of money; Sandy, a doctor, makes plenty of money. Boys back then, we did okay, we made out. But after they leave college, Carnal Knowledge progresses by the rake’s decline, sure as gravity.

We don’t see their marriages, their divorces. Jonathan does meet a girl, Bobbie (Ann-Margret), with whom he “shacks up,” but not before limiting their involvement. He wants to lay his cards on the table so “there can be no possibility of a misunderstanding. I don’t know how many business deals I’ve seen come to grief. . . .” He wants what he wants, which is her when he wants her. She quits modeling, lies in bed a lot, dreams of being a mother. Jonathan spends a lot of time in the shower, now alone.

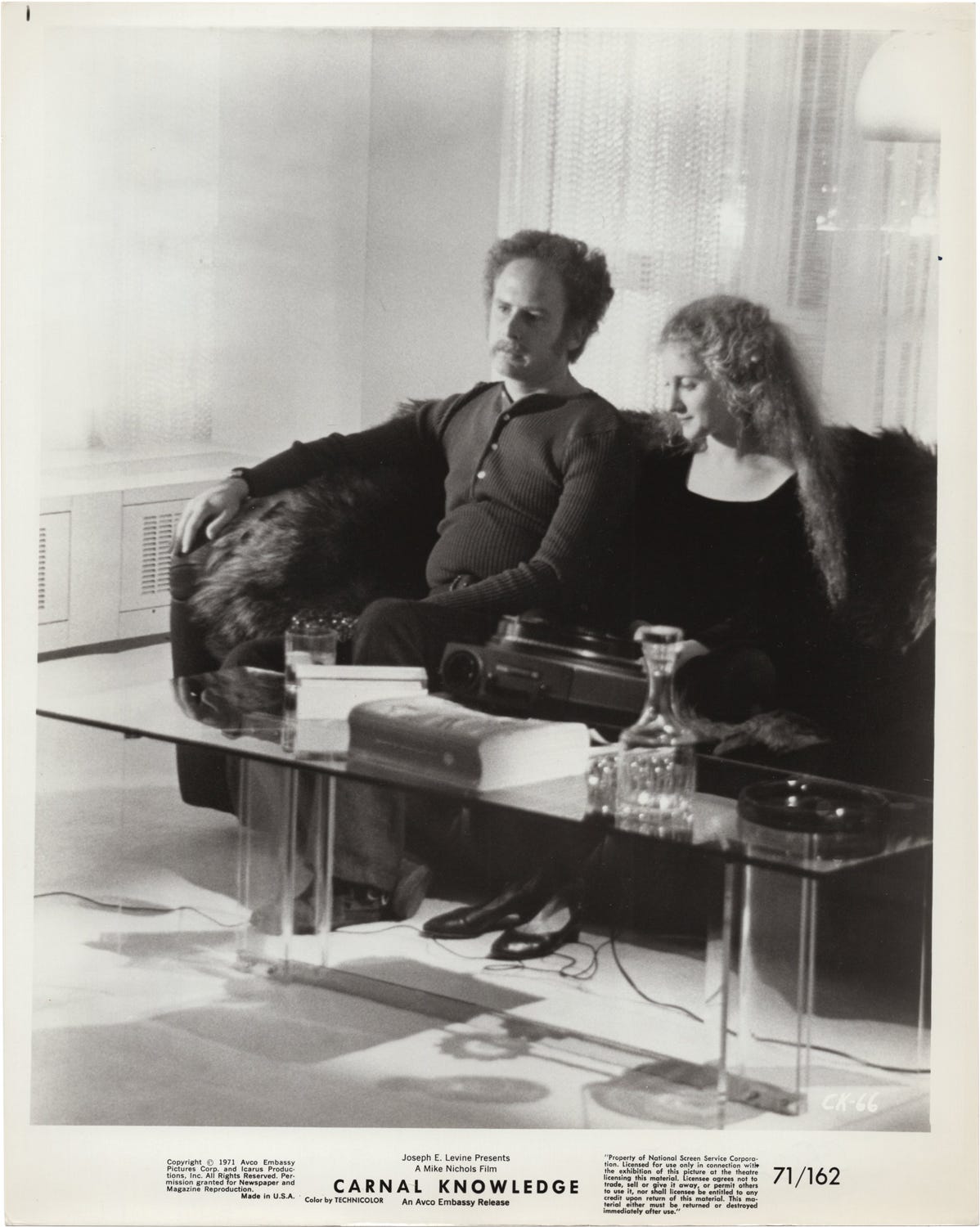

One night, late Sixties now, Sandy shows up at Jonathan’s white-on-white penthouse to watch a slide show, the history in pictures of love between men and women of my generation, the Silent, Smug, Cunning, Can-Do Generation. Women and kids, all “girls,” flash on the screen. This one Jonathan “banged,” that one broke his balls. Sandy and his latest girlfriend, a fruit-and-nut eater (Carol Kane) from Greenwich Village, deplore Jonathan’s bad character. Sandy wears blue jeans, has had his consciousness raised (and been laid plenty). Sandy’s bullshit artist is that pathetic figure of our time, the born-again feminist looking to score, as ever, when she falls asleep.

After the slide show, Jonathan goes to a whore (Rita Moreno). If she says just the right words, tells him how just he is and how unjust women are, maybe he can get it up, maybe. Bullshit artist! His balls are broken. His heart is broken. What we did, what we do still—a lot of us—makes for a weird way to put in hours. The unconnected self, even with its plug in a socket, is an impotent thing. Nota bene, today’s younger generation as well as my own, on this one.