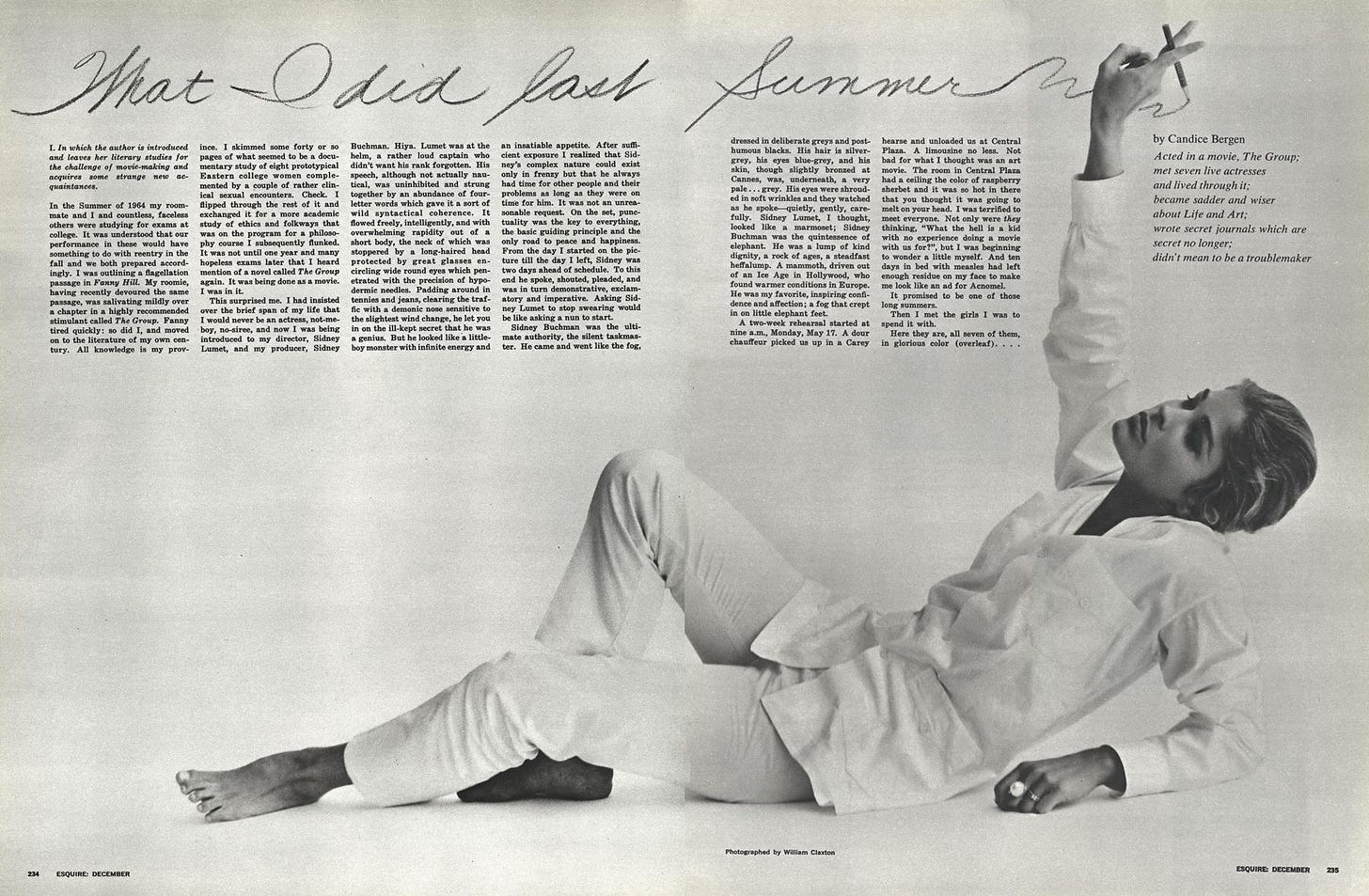

By Candice Bergen/Photographs by William Claxton

From Esquire

December 1965

I. In which the author is introduced and leaves her literary studies for the challenge of movie-making and acquires some strange new acquaintances.

In the Summer of 1964 my roommate and I and countless, faceless others were studying for exams at college. It was understood that our performance in these would have something to do with reentry in the fall and we both prepared accordingly. I was outlining a flagellation passage in Fanny Hill. My roomie, having recently devoured the same passage, was salivating mildly over a chapter in a highly recommended stimulant called The Group. Fanny tired quickly: so did I, and moved on to the literature of my own century. All knowledge is my province. I skimmed some forty or so pages of what seemed to be a documentary study of eight prototypical Eastern college women complemented by a couple of rather clinical sexual encounters. Check. I flipped through the rest of it and exchanged it for a more academic study of ethics and folkways that was on the program for a philosophy course I subsequently flunked. It was not until one year and many hopeless exams later that I heard mention of a novel called The Group again. It was being done as a movie. I was in it.

This surprised me. I had insisted over the brief span of my life that I would never be an actress, not-me-boy, no-siree, and now I was being introduced to my director, Sidney Lumet, and my producer, Sidney Buchman. Hiya. Lumet was at the helm, a rather loud captain who didn’t want his rank forgotten. His speech, although not actually nautical, was uninhibited and strung together by an abundance of four-letter words which gave it a sort of wild syntactical coherence. It flowed freely, intelligently, and with overwhelming rapidity out of a short body, the neck of which was stoppered by a long-haired head protected by great glasses encircling wide round eyes which penetrated with the precision of hypodermic needles. Padding around in tennies and jeans, clearing the traffic with a demonic nose sensitive to the slightest wind change, he let you in on the ill-kept secret that he was a genius. But he looked like a little-boy monster with infinite energy and an insatiable appetite. After sufficient exposure I realized that Sidney’s complex nature could exist only in frenzy but that he always had time for other people and their problems as long as they were on time for him. It was not an unreasonable request. On the set, punctuality was the key to everything, the basic guiding principle and the only road to peace and happiness. From the day I started on the picture till the day I left, Sidney was two days ahead of schedule. To this end he spoke, shouted, pleaded, and was in turn demonstrative, exclamatory and imperative. Asking Sidney Lumet to stop swearing would be like asking a nun to start.

Sidney Buchman was the ultimate authority, the silent taskmaster. He came and went like the fog, dressed in deliberate greys and posthumous blacks. His hair is silver-grey, his eyes blue-grey, and his skin, though slightly bronzed at Cannes, was, underneath, a very pale . . . grey. His eyes were shrouded in soft wrinkles and they watched as he spoke—quietly, gently, carefully. Sidney Lumet, I thought, looked like a marmoset; Sidney Buchman was the quintessence of elephant. He was a lump of kind dignity, a rock of ages, a steadfast heffalump. A mammoth, driven out of an Ice Age in Hollywood, who found warmer conditions in Europe. He was my favorite, inspiring confidence and affection; a fog that crept in on little elephant feet.

A two-week rehearsal started at nine a.m., Monday, May 17. A dour chauffeur picked us up in a Carey hearse and unloaded us at Central Plaza. A limousine no less. Not bad for what I thought was an art movie. The room in Central Plaza had a ceiling the color of raspberry sherbet and it was so hot in there that you thought it was going to melt on your head. I was terrified to meet everyone. Not only were they thinking, “What the hell is a kid with no experience doing a movie with us for?”, but I was beginning to wonder a little myself. And ten days in bed with measles had left enough residue on my face to make me look like an ad for Acnomel.

It promised to be one of those long summers.

Then I met the girls I was to spend it with.

Here they are, all seven of them, in glorious color (overleaf). . . .

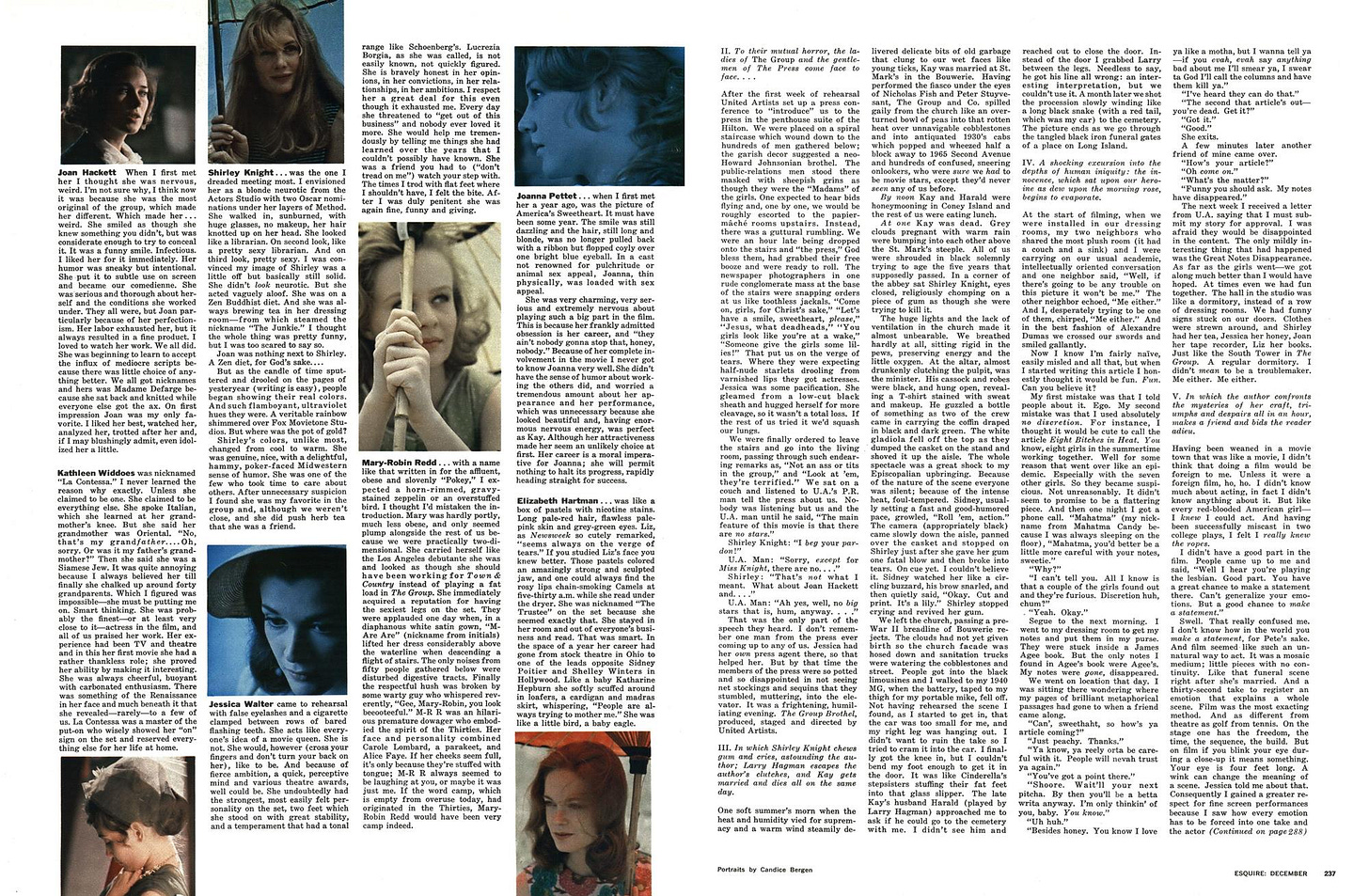

Joan Hackett When I first met her I thought she was nervous, weird. I’m not sure why, I think now it was because she was the most original of the group, which made her different. Which made her . . . weird. She smiled as though she knew something you didn’t, but was considerate enough to try to conceal it. It was a funny smile. Infectious. I liked her for it immediately. Her humor was sneaky but intentional. She put it to subtle use on screen and became our comedienne. She was serious and thorough about herself and the conditions she worked under. They all were, but Joan particularly because of her perfectionism. Her labor exhausted her, but it always resulted in a fine product. I loved to watch her work. We all did. She was beginning to learn to accept the influx of mediocre scripts because there was little choice of anything better. We all got nicknames and hers was Madame Defarge because she sat back and knitted while everyone else got the ax. On first impression Joan was my only favorite. I liked her best, watched her, analyzed her, trotted after her and, if I may blushingly admit, even idolized her a little.

Kathleen Widdoes was nicknamed “La Contessa.” I never learned the reason why exactly. Unless she claimed to be one. She claimed to be everything else. She spoke Italian, which she learned at her grandmother’s knee. But she said her grandmother was Oriental. “No, that’s my grandfather . . . . Oh, sorry. Or was it my father’s grandmother?” Then she said she was a Siamese Jew. It was quite annoying because I always believed her till finally she chalked up around forty grandparents. Which I figured was impossible—she must be putting me on. Smart thinking. She was probably the finest—or at least very close to it—actress in the film, and all of us praised her work. Her experience had been TV and theatre and in this her first movie she had a rather thankless role; she proved her ability by making it interesting. She was always cheerful, buoyant with carbonated enthusiasm. There was something of the Renaissance in her face and much beneath it that she revealed—rarely—to a few of us. La Contessa was a master of the put-on who wisely showed her “on” sign on the set and reserved everything else for her life at home.

Shirley Knight . . . was the one I dreaded meeting most. I envisioned her as a blonde neurotic from the Actors Studio with two Oscar nominations under her layers of Method. She walked in, sunburned, with huge glasses, no makeup, her hair knotted up on her head. She looked like a librarian. On second look, like a pretty sexy librarian. And on third look, pretty sexy. I was convinced my image of Shirley was a little off but basically still solid. She didn’t look neurotic. But she acted vaguely aloof. She was on a Zen Buddhist diet. And she was always brewing tea in her dressing room—from which steamed the nickname “The Junkie.” I thought the whole thing was pretty funny, but I was too scared to say so.

Joan was nothing next to Shirley. A Zen diet, for God’s sake . . . .

But as the candle of time sputtered and drooled on the pages of yesteryear (writing is easy), people began showing their real colors. And such flamboyant, ultraviolet hues they were. A veritable rainbow shimmered over Fox Movietone Studios. But where was the pot of gold?

Shirley’s colors, unlike most, changed from cool to warm. She was genuine, nice, with a delightful, hammy, poker-faced Midwestern sense of humor. She was one of the few who took time to care about others. After unnecessary suspicion I found she was my favorite in the group and, although we weren’t close, and she did push herb tea that she was a friend.

Jessica Walter came to rehearsal with false eyelashes and a cigarette clamped between rows of bared flashing teeth. She acts like everyone’s idea of a movie queen. She is not. She would, however (cross your fingers and don’t turn your back on her), like to be. And because of fierce ambition, a quick, perceptive mind and various theatre awards, well could be. She undoubtedly had the strongest, most easily felt personality on the set, two feet which she stood on with great stability, and a temperament that had a tonal range like Schoenberg’s. Lucrezia Borgia, as she was called, is not easily known, not quickly figured. She is bravely honest in her opinions, in her convictions, in her relationships, in her ambitions. I respect her a great deal for this even though it exhausted me. Every day she threatened to “get out of this business” and nobody ever loved it more. She would help me tremendously by telling me things she had learned over the years that I couldn’t possibly have known. She was a friend you had to (“don’t tread on me”) watch your step with. The times I trod with flat feet where I shouldn’t have, I felt the bite. After I was duly penitent she was again fine, funny and giving.

Mary-Robin Redd . . . with a name like that written in for the affluent, obese and slovenly “Pokey,” I expected a horn-rimmed, gravy-stained zeppelin or an overstuffed bird. I thought I’d mistaken the introduction. Mary was hardly portly, much less obese, and only seemed plump alongside the rest of us because we were practically two-dimensional. She carried herself like the Los Angeles debutante she was and looked as though she should have been working for Town & Country instead of playing a fat load in The Group. She immediately acquired a reputation for having the sexiest legs on the set. They were applauded one day when, in a diaphanous white satin gown, “M-Are Are” (nickname from initials) lifted her dress considerably above the waterline when descending a flight of stairs. The only noises from fifty people gathered below were disturbed digestive tracts. Finally the respectful hush was broken by some warty guy who whispered reverently, “Gee, Mary-Robin, you look beeooteeful.” M-R R was an hilarious premature dowager who embodied the spirit of the Thirties. Her face and personality combined Carole Lombard, a parakeet, and Alice Faye. If her cheeks seem full, it’s only because they’re stuffed with tongue; M-R R always seemed to be laughing at you, or maybe it was just me. If the word camp, which is empty from overuse today, had originated in the Thirties, Mary-Robin Redd would have been very camp indeed.

Joanna Pettet . . . when I first met her a year ago, was the picture of America’s Sweetheart. It must have been some year. The smile was still dazzling and the hair, still long and blonde, was no longer pulled back with a ribbon but flopped coyly over one bright blue eyeball. In a cast not renowned for pulchritude or animal sex appeal, Joanna, thin physically, was loaded with sex appeal.

She was very charming, very serious and extremely nervous about playing such a big part in the film. This is because her frankly admitted obsession is her career, and “they ain’t nobody gonna stop that, honey, nobody.” Because of her complete involvement in the movie I never got to know Joanna very well. She didn’t have the sense of humor about working that the others did, and worried a tremendous amount about her appearance and her performance, which was unnecessary because she looked beautiful and, having enormous nervous energy, was perfect as Kay. Although her attractiveness made her seem an unlikely choice at first. Her career is a moral imperative for Joanna; she will permit nothing to halt its progress, rapidly heading straight for success.

Elizabeth Hartman . . . was like a box of pastels with nicotine stains. Long pale-red hair, flawless pale-pink skin and grey-green eyes. Liz, as Newsweek so cutely remarked, “seems always on the verge of tears.” If you studied Liz’s face you knew better. Those pastels colored an amazingly strong and sculpted jaw, and one could always find the rosy lips chain-smoking Camels at five-thirty a.m. while she read under the dryer. She was nicknamed “The Trustee” on the set because she seemed exactly that. She stayed in her room and out of everyone’s business and read. That was smart. In the space of a year her career had gone from stock theatre in Ohio to one of the leads opposite Sidney Poitier and Shelley Winters in Hollywood. Like a baby Katharine Hepburn she softly scuffed around in loafers, a cardigan and madras skirt, whispering, “People are always trying to mother me.” She was like a little bird, a baby eagle.

II. To their mutual horror, the ladies of The Group and the gentlemen of The Press come face to face. . . .

After the first week of rehearsal United Artists set up a press conference to “introduce” us to the press in the penthouse suite of the Hilton. We were placed on a spiral staircase which wound down to the hundreds of men gathered below; the garish decor suggested a neo-Howard Johnsonian brothel. The public-relations men stood there masked with sheepish grins as though they were the “Madams” of the girls. One expected to hear bids flying and, one by one, we would be roughly escorted to the papier-mâché rooms upstairs. Instead, there was a guttural rumbling. We were an hour late being dropped onto the stairs and “the press,” God bless them, had grabbed their free booze and were ready to roll. The newspaper photographers in one rude conglomerate mass at the base of the stairs were snapping orders at us like toothless jackals. “Come on, girls, for Christ’s sake,” “Let’s have a smile, sweetheart, please,” “Jesus, what deadheads,” “You girls look like you’re at a wake,” “Someone give the girls some lilies!” That put us on the verge of tears. Where they were expecting half-nude starlets drooling from varnished lips they got actresses. Jessica was some pacification. She gleamed from a low-cut black sheath and hugged herself for more cleavage, so it wasn’t a total loss. If the rest of us tried it we’d squash our lungs.

We were finally ordered to leave the stairs and go into the living room, passing through such endearing remarks as, “Not an ass or tits in the group,” and “Look at ’em, they’re terrified.” We sat on a couch and listened to U.A.’s P.R. man tell the press about us. Nobody was listening but us and the U.A. man until he said, “The main feature of this movie is that there are no stars.”

Shirley Knight: “I beg your pardon!”

U.A. Man: “Sorry, except for Miss Knight, there are no.. . .”

Shirley: “That’s not what I meant. What about Joan Hackett and. . . .”

U.A. Man: “Ah yes, well, no big stars that is, hum, anyway. . . .”

That was the only part of the speech they heard. I don’t remember one man from the press ever coming up to any of us. Jessica had her own press agent there, so that helped her. But by that time the members of the press were so potted and so disappointed in not seeing net stockings and sequins that they stumbled, muttering, into the elevator. It was a frightening, humiliating evening. The Group Brothel, produced, staged and directed by United Artists.

III. In which Shirley Knight chews gum and cries, astounding the author; Larry Hagman escapes the author’s clutches, and Kay gets married and dies all on the same day.

One soft summer’s morn when the heat and humidity vied for supremacy and a warm wind steamily delivered delicate bits of old garbage that clung to our wet faces like young ticks, Kay was married at St. Mark’s in the Bouwerie. Having performed the fiasco under the eyes of Nicholas Fish and Peter Stuyvesant, The Group and Co. spilled gaily from the church like an overturned bowl of peas into that rotten heat over unnavigable cobblestones and into antiquated 1930’s cabs which popped and wheezed half a block away to 1965 Second Avenue and hundreds of confused, sneering onlookers, who were sure we had to be movie stars, except they’d never seen any of us before.

By noon Kay and Harald were honeymooning in Coney Island and the rest of us were eating lunch.

At one Kay was dead. Grey clouds pregnant with warm rain were bumping into each other above the St. Mark’s steeple. All of us were shrouded in black solemnly trying to age the five years that supposedly passed. In a corner of the abbey sat Shirley Knight, eyes closed, religiously chomping on a piece of gum as though she were trying to kill it.

The huge lights and the lack of ventilation in the church made it almost unbearable. We breathed hardly at all, sitting rigid in the pews, preserving energy and the little oxygen. At the altar, almost drunkenly clutching the pulpit, was the minister. His cassock and robes were black, and hung open, revealing a T-shirt stained with sweat and makeup. He guzzled a bottle of something as two of the crew came in carrying the coffin draped in black and dark green. The white gladiola fell off the top as they dumped the casket on the stand and shoved it up the aisle. The whole spectacle was a great shock to my Episcopalian upbringing. Because of the nature of the scene everyone was silent; because of the intense heat, foul-tempered. Sidney, usually setting a fast and good-humored pace, growled, “Roll ’em, action.”

We left the church, passing a pre-War II breadline of Bouwerie rejects. The clouds had not yet given birth so the church facade was hosed down and sanitation trucks were watering the cobblestones and street. People got into the black limousines and I walked to my 1940 MG, when the battery, taped to my thigh for my portable mike, fell off. Not having rehearsed the scene I found, as I started to get in, that the car was too small for me, and my right leg was hanging out. I didn’t want to ruin the take so I tried to cram it into the car. I finally got the knee in, but I couldn’t bend my foot enough to get it in the door. It was like Cinderella’s stepsisters stuffing their fat feet into that glass slipper. The late Kay’s husband Harald (played by Larry Hagman) approached me to ask if he could go to the cemetery with me. I didn’t see him and reached out to close the door. Instead of the door I grabbed Larry between the legs. Needless to say, he got his line all wrong: an interesting interpretation, but we couldn’t use it. A month later we shot the procession slowly winding like a long black snake (with a red tail, which was my car) to the cemetery. The picture ends as we go through the tangled black iron funeral gates of a place on Long Island.

IV. A shocking excursion into the depths of human iniquity: the innocence, which sat upon our heroine as dew upon the morning rose, begins to evaporate.

At the start of filming, when we were installed in our dressing rooms, my two neighbors who shared the most plush room (it had a couch and a sink) and I were carrying on our usual academic, intellectually oriented conversation and one neighbor said, “Well, if there’s going to be any trouble on this picture it won’t be me.” The other neighbor echoed, “Me either.” And I, desperately trying to be one of them, chirped, “Me either.” And in the best fashion of Alexandre Dumas we crossed our swords and smiled gallantly.

Now I know I’m fairly naïve, easily misled and all that, but when I started writing this article I honestly thought it would be fun. Fun. Can you believe it?

My first mistake was that I told people about it. Ego. My second mistake was that I used absolutely no discretion. For instance, I thought it would be cute to call the article Eight Bitches in Heat. You know, eight girls in the summertime working together. Well for some reason that went over like an epidemic. Especially with the seven other girls. So they became suspicious. Not unreasonably. It didn’t seem to promise to be a flattering piece. And then one night I got a phone call. “Mahatma” (my nickname from Mahatma Candy because I was always sleeping on the floor), “Mahatma, you’d better be a little more careful with your notes, sweetie.”

“Why?”

“I can’t tell you. All I know is that a couple of the girls found out and they’re furious. Discretion huh, chum?”

“Yeah. Okay.”

Segue to the next morning. I went to my dressing room to get my notes and put them in my purse. They were stuck inside a James Agee book. But the only notes I found in Agee’s book were Agee’s. My notes were gone, disappeared.

We went on location that day. I was sitting there wondering where my pages of brilliant metaphorical passages had gone to when a friend came along.

“Can’, sweethaht, so how’s ya article coming?”

“Just peachy. Thanks.”

“Ya know, ya reely orta be careful with it. People will nevah trust ya again.”

“You’ve got a point there.”

“Shoore. Wait’ll your next pitcha. By then you’ll be a betta writa anyway. I’m only thinkin’ of you, baby. You know.”

“Uh huh.”

“Besides honey. You know I love ya like a motha, but I wanna tell ya—if you evah, evah say anything bad about me I’ll smear ya, I swear ta God I’ll call the columns and have them kill ya.”

“I’ve heard they can do that.”

“The second that article’s out—you’re dead. Get it?”

“Got it.”

“Good.”

She exits.

A few minutes later another friend of mine came over.

“How’s your article?”

“Oh come on.”

“What’s the matter?”

“Funny you should ask. My notes have disappeared.”

The next week I received a letter from U.A. saying that I must submit my story for approval. I was afraid they would be disappointed in the content. The only mildly interesting thing that had happened was the Great Notes Disappearance. As far as the girls went—we got along much better than I would have hoped. At times even we had fun together. The hall in the studio was like a dormitory, instead of a row of dressing rooms. We had funny signs stuck on our doors. Clothes were strewn around, and Shirley had her tea, Jessica her honey, Joan her tape recorder, Liz her books. Just like the South Tower in The Group. A regular dormitory. I didn’t mean to be a troublemaker. Me either. Me either.

V. In which the author confronts the mysteries of her craft, triumphs and despairs all in an hour, makes a friend and bids the reader adieu.

Having been weaned in a movie town that was like a movie, I didn’t think that doing a film would be foreign to me. Unless it were a foreign film, ho, ho. I didn’t know much about acting, in fact I didn’t know anything about it. But like every red-blooded American girl—I knew I could act. And having been successfully miscast in two college plays, I felt I really knew the ropes.

Swell. That really confused me. I don’t know how in the world you make a statement, for Pete’s sake. And film seemed like such an unnatural way to act. It was a mosaic medium; little pieces with no continuity. Like that funeral scene right after she’s married. And a thirty-second take to register an emotion that explains a whole scene. Film was the most exacting method. And as different from theatre as golf from tennis. On the stage one has the freedom, the time, the sequence, the build. But on film if you blink your eye during a close-up it means something. Your eye is four feet long. A wink can change the meaning of a scene. Jessica told me about that. Consequently I gained a greater respect for fine screen performances because I saw how every emotion has to be forced into one take and the actor has to reconstruct the sequence in his own mind. Like Shirley crying on cue, or Jessica sobbing over baked Alaska, which we ate for a scene that took two weeks to shoot.

I had been on the picture for nine weeks. Out of that time I worked one day. What I mean is that only one day did I go home feeling proud and satisfied of the work I’d done. It happened during the eighth week, and seven weeks of boredom and depression on the film went into it.

We were shooting the scene in Helena’s apartment after Kay’s death. It was a long, talky scene and Sidney shot two master angles and then came in on each one of us for individual close-ups. It was the last scene to be shot. I didn’t know what in the world to do. I watched as Joan, Jessica, Kathy, Mary, Liz and Shirley ripped off great closeups, and then it was my turn and I was stuck. I’d never had the nerve to ask Shirley what in the world she thought about when she was chewing her gum for the funeral scene. How do you prepare? I mentally slew everyone I loved, my dog, my family, my friends, and had them all in the same casket, bleeding and dismembered. Great image, but it didn’t work. I knew that this was the one time in the movie where I had to show great emotion for the first time. And I couldn’t get sad. So I gave up. Millions of people do crying scenes in movies every year and I can’t even get worried. I think Sidney was though. He’d set the shot up and came over to me. I guess I looked happy. He looked sad. “Come on, babe. Work on this now.”

“But Sidney, I am.” Sidney started talking to me. I’m not sure what he said, but the way his face was all screwed up, his intensity, and his frantic whispered words all triggered something. I asked him to keep talking. He went on hammering in.

“You can’t believe it. Best friend. Dead. Fight the antagonism with Libby. Can’t believe it. Best friend, best friend, best . . . roll ’em, action.”

I started to gasp for breath, and my throat was swollen and my eyes were hot and tears sat right on the balcony of my eyes. As I did the scene suddenly the emotion made use of it and the lines killed me. I knew that I couldn’t cry openly because it wouldn’t be as effective and it wouldn’t be right. But I was really crying. My best friend really was dead and the scene ended and Sidney said, “Cut. Lily.” I calmed down a little, not too much because I didn’t want anyone to miss it. And I took my time going upstairs so everyone could congratulate me, surfeit me with praise. But no one did. I knew every actress could do it, but this time I did it for the first time. I felt like I had worked and done a good job. The cameraman came over to me with tears in his eyes and that was a lovely sight. But no one else. They must have been overwhelmed, I figured. That was it. They couldn’t take it. I was right. They couldn’t. I had made a boo-boo. I had not matched the master take where I wasn’t crying and I had, supposedly, thrown the other girls off because they weren’t expecting it. One of my favorites came up and said, “Candle-boy, did you evah shock us! I mean we didn’t know you were going to do that.”

“Neither did I.”

“Well, boobie, I would have done the scene much differently. You really scared us. What did Sidney tell you anyway? Boy. Don’t evah do that again!”

I could not believe it. I had done it again. Stirred the infested waters. I walked upstairs determined to be a tender martyr. I got the same thing from a girl I really like. It just isn’t fair, I thought. I do good work, but I do it wrong and I get clobbered. If you don’t think I was strangled with self-pity . . . then Shirley knocked on the door and came in. She looked like St. Francis. She said that it was a fine piece of work and that it surprised people and not to pay attention and that I could be a good actress if I worked and so on, and from that day on I really loved Shirley and all her tea leaves and gave her great respect because no one else would take the time to consider how another felt, and be secure enough in herself to give some of that security to me. And so to you, Shirley Knight, I am forever grateful. So ends the beginner’s episode on acting and what it did for me. Nothing. But one day of self-pride and satisfaction. Amen. Thank you and good night.

© Esquire