When the television series Succession became successful and urgently needed in the homes and conversations of so many people, it was a great joy to watch as people fell in love with J. Smith Cameron, whose Gerri led her to be recognized as the redoubtable actress she is, but which also cast her as a meme, an avatar, and a role model. Fewer things make me happier than to see a friend (and, full disclosure, I consider J. to be a friend) lovingly imitated at a party where the age-old Truth Game is played with Gerri as the persona most often adopted.

Now cast as an elder gay, I am often asked by the younger folk to describe things I’ve seen, people I’ve known, bodies I’ve buried (some happily, some sadly). It makes me very happy when I am asked to talk about my history with J. Smith-Cameron.

I first met J. in 1991, when I interviewed her for what was then called The West Side Spirit, a free newspaper that wanted to highlight those who lived on one side of the island of Manhattan. I fudged things a bit: I told the editor of the newspaper that performing in a theatre on the West Side gave someone, at least temporarily, a residence desired by the publication. It worked.

J. was then appearing in Timberlake Wertenbaker’s Our Country’s Good, and I was taken both by her talent and her striking resemblance to Barbara Baxley, an actress much loved by Tennessee Williams, who had died in 1990. J. not only had her lovely and prominent eyes, but an asperity—stylish, sometimes lethal, often touching—that evoked the actress.

The day on which J. and I met was charmed—for me, at least. We met at Good Enough To Eat, which was then on Amsterdam Avenue and 83rd Street, and, right at the entrance, was the actress Jane Adams, as magical and bright as J. After an interview over lunch, J. and I wandered through the late and lamented Shakespeare & Company bookstore. J. was roaming the aisles looking for a book on baseball, all the while offering commentary on other books and authors. It was clear that she was intelligent, widely read, and never cruel. J. had and still has a remarkable ability to explain why she dislikes something without ever lowering the conversation or herself. Her ego is not one that finds her needing to appear smarter. I have never known her to disparage someone for holding an opinion counter to her own. I have known her to become incensed when she witnesses cruelty in others, or when she feels that a friend has been hurt, or when she has to endure a diatribe against the theatre or television or the state of the world. J. lives and loves and works in the world, and she will defend it until the end. She does not piss and moan, which in and of itself renders her worthy of some sort of canonization.

Another thing: J. can find good caramel or chocolate anywhere, at any time. She shares. Not only did I receive a bountiful caramel cake from her when my mother died, but she later wasted no time in introducing me to tablet, a Scottish confection made of sugar, condensed milk, and butter: a penuche with a kilt in its past. She is dangerous in that way.

However, the real danger to deal with regarding J. Smith-Cameron is her talent. Smith-Cameron is an actress people talk about, wonder about, emulate. Directors, actors, writers have gathered at various times to talk about their experiences with this actress, and while descriptions and encomiums fly, the one thing upon which everyone can agree is that J. Smith-Cameron is an intelligent actress: Nothing, not even a skimpily written cameo in a film, can be diluted once she inhabits the part and the space that is required.

Here are my memories of two of her performances. More to come (if she can stand it).

First examples:

Our Country’s Good by Timberlake Wertenbaker. Broadway, Nederlander Theatre, 1991.

It was this play that introduced me to Smith-Cameron, and it was the final production of the pallid 1990-91 season. It is surprising to me that Our Country’s Good has not been revived, since in our current wasting theatre, it might rejoice in the play’s theory that the theatre—even in a deracinated form in an Australian penal colony—is what we need, what revives and restores us. Our Country’s Good doesn’t work, really, but it gave a stage full of talented actors (Peter Frechette, Cherry Jones, Amelia Campbell, Tracey Ellis, Richard Poe, Sam Tsoutsouvas) space to play, to craft intriguing characters.

Cherry Jones transformed from a scabrous inmate with decaying teeth into a beguiling chateleine, and Smith-Cameron, feisty, angry, every part of her body wary and alert, was a study in comedy. You watched her hobble across the stage as an amateur actress might, beguiled by attention, a costume, some makeup, then you saw her gain confidence and move with some semblance of grace. Her grime held some promise of charm, and her character best represented all of those in the audience who lived in fear not only of a penal colony, but of being thrust on a stage and asked to “act.” The brutality of the penal colony was sometimes forgotten in all the scattering about the stage, but the peril—offstage, yes, but deep within the minds of every character—was most evident in Smith-Cameron’s eyes, the jerks of her head to let us know that she could hear the screams of punishment in the distance; she could see where this company of “actors” was headed. An actress with whom I saw Our Country’s Good remarked on Smith-Cameron’s ability to expand the play in which she was appearing, but without any distractions, any upstaging, any commentary. She was true to her character, lived in the atmosphere Wertenbaker created, and served as a corporeal timeline for the play. Unlike others in the play, Smith-Cameron was not given what are called “big moments”— an outburst, a searing monologue— but the director of the play (Mark Lamos) was wise to keep her in our line of vision, to see what effect the play was having on her, as both an actress and a character in a play. As Marian Seldes said after we had seen it: “I lived the play through her, and when she walked off the stage with the others toward…what? I went with her.”

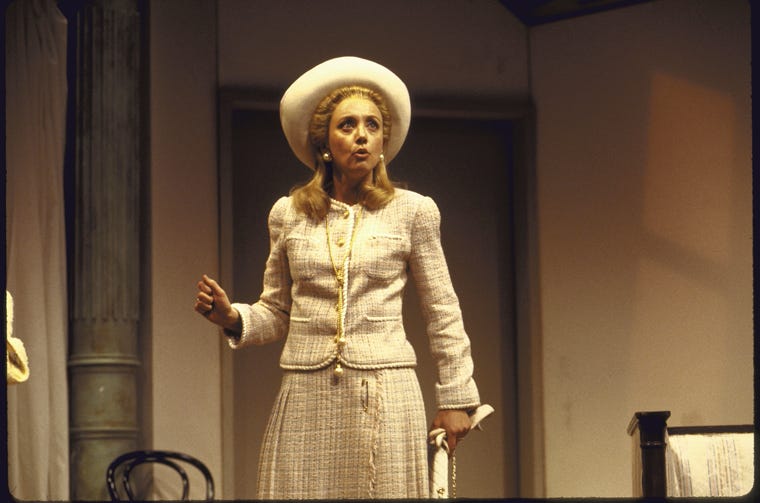

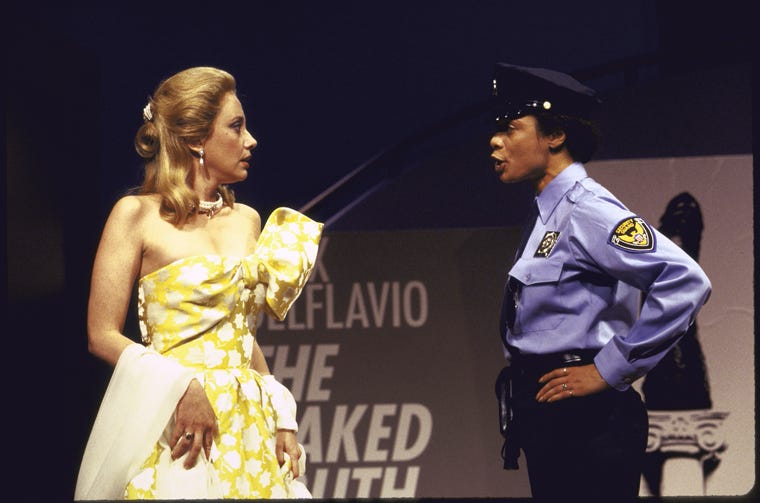

The Naked Truth by Paul Rudnick. Off-Broadway, WPA Theatre, 1994.

J. Smith-Cameron was Sissy Bemiss in Rudnick’s riotous farce, in which some Manhattan doyennes found themselves up against some photographic representations of sex, the activity to which they were not devoted in some form of charity or support or curation. Smith-Cameron was the daughter of Nan Bemiss, an exemplar of Upper East Side propriety, who ventures downtown to beg a particular photographer to not share with a certain museum his bold works, which would appear to be not unlike those of Robert Mapplethorpe. A trip downtown (do with that what you will) is an adventure for this type of woman, who also has some difficulty with the word “dildo,” until she discovers it has an inherent sweetness, and sounds as if it could be a sea chantey.

The daughter of such a woman is of course a specimen who did not fall far from the well-upholstered tree, and Smith-Cameron was coiled from her first entrance, primed to briefly fight what the world might bring her, and then to acquiesce to it. Sissy welcomes the interruptions to her well-ordered life, but she is also terrified that hers might not be the best responses. It is not that Sissy has her finger in the wind to determine what she must say: her entire being is extended toward certain people and neighborhoods for any incoming data on what she should do or say, and her posture revealed it. Smith-Cameron was attired in clothes that were suitable for a porcelain doll, but a porcelain doll that had Tourette’s and a sexual addiction. I remember Smith-Cameron’s hands, always up, often extended, to grab whatever might come around, but also clenched, because it might be dirty, grimy, not well-scented, not spritzed with anything of higher vintage than Jean Nate. Smith-Cameron referred to the use of her limbs as “puppet hands,” but was generous in allowing that those were not her idea, but something she had cadged from Kristine Nielsen.

Vincent Canby, in his review of The Naked Truth for the New York Times, wrote that Sissy had a gift for the punishing anticlimax, but I disagree: Sissy is all about climaxes, even though she appears never to have had one. Perhaps a Sissy, as Rudnick and Smith-Cameron crafted her, can only enjoy a verbal climax, an orgy of words, friction among ideas, no matter how vapid. When The Naked Truth was playing, I was managing a bakery called Ecce Panis, on Madison Avenue at 90th Street. Ecce Panis, the ovens of The Sign of the Dove, was known for offering abundant samples, which were placed in wooden bowls along one side of the shop. Every day at the same time, a swarm of girls from the nearby “good schools” would adhere to these bowls, gobbling every crumb of the samples, and, in lockjaw and vocal fry, recount their day. I remember one girl saying “Did you see that pimple—that angry mountain—that Celestine had?” My coworkers wondered why I didn’t remove the samples before they could gather and peck, but I wanted to hear the dialogue. I wanted to remember J. Smith-Cameron, who had given us an older version of this sort of girl, pampered and enraged and always, always hungry. Ecce Panis offered a chocolate bread that could be slathered with mascarpone, and I remember one girl, slightly cross-eyed, asking if our mascarpone was “domestic.” I told her the mascarpone behaved well, but the crème fraîche was a little rowdy. Her response? “I like gays,” she said. “All of our male friends are gay.” I bet.

I disagreed with Vincent Canby when he claimed that the second act of The Naked Truth went awry: The second act of The Naked Truth went where it had to go—toward a sort of chaos that was full of mistaken assumptions, embarrassing questions, and a desire to avoid any hint of smut, even though you just knew everyone was poking around to find some. Fear of sex, along with our desire to control its presentation, can be labeled as censorship, but it can also be exhilarating. The control of what others can see—particularly if it goes against your morals or your standards of taste and size—is about power. So is some sex. What I saw in The Naked Truth, expertly staged by Christopher Ashley, was a confluence of cultures, skins, agendas. It was pretty blissful.

Few can write dialogue as witty and scathing (and correct) as Paul Rudnick, and J. Smith-Cameron was his ideal interpreter. (I wanted to write “mouthpiece,” if only because I feel it would delight and scandalize the character she was playing.) That intelligence to which I referred earlier is what galvanizes her delivery of humor. The ideal of all actors is to give the impression that you are living your character for the very first time, an illusion of freshness and discovery. J. Smith-Cameron is a master of this ability, and so much of the humor in The Naked Truth grew out out of the sense that her Sissy was gauging and editing what she said and thought in real time. Smith-Cameron wasn’t “landing” a joke—she was channeling a woman who learned most things from captions in swanky magazines or overheard at Scully & Scully. Whether her line of dialogue was funny or shocking to her was something she seemed to be discovering, her head jerking about as if listening for bird calls.

TO BE CONTINUED…