Alec Guinness: The Simplest Apostolic Act

"We show up for others. That would seem to be to be the minimum we can do. To be present. To do what we can."

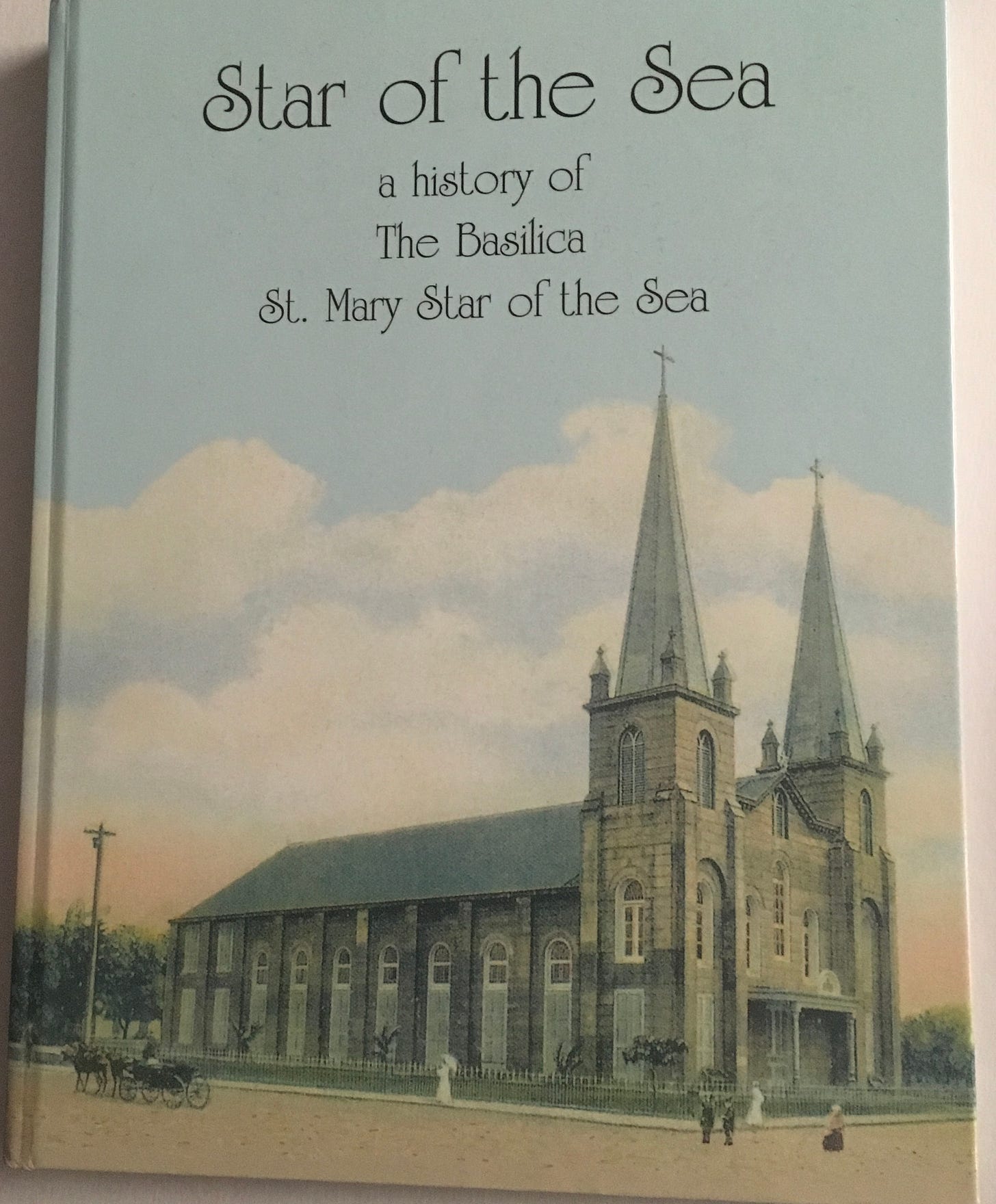

For reasons that many of his friends found inexplicable, Tennessee Williams began a fervent though erratic study of Roman Catholicism in the 1960s. In 1969, Tennessee converted to the religion at St. Mary, Star of the Sea Church in Key West, Florida. To his adviser, Father LeRoy, Tennessee claimed that he wanted to get his goodness back.

Tennessee felt adrift in the 1960s, dramatically claiming that his talent had shriveled or that it was hiding, and when he “found” it, it was like a ball of mercury in his hand: impossible to grasp or to take any useful shape. Talent, or inspiration, would be found in the “fog” that might arise when a woman’s voice spoke to him and led him toward a story. Tennessee had abused drugs and alcohol, leading him to feel that he had missed so much. More than anything, he had missed himself, abandoned himself, later claiming that he would not do to an animal what he had done to this man he called—in times of extremis—Thomas Lanier Williams: He had dumped him off, unsupervised, vulnerable.

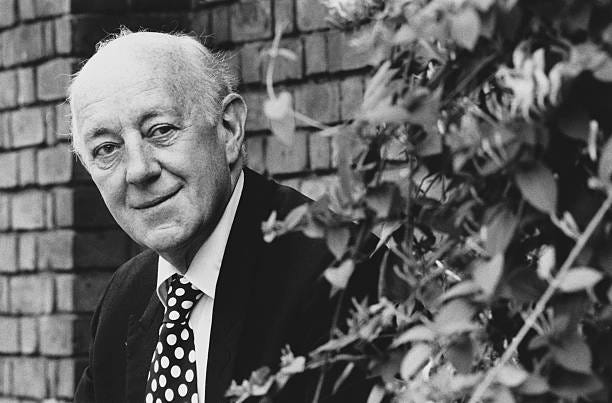

Tennessee claimed he had read an article about the Catholic conversion of Alec Guinness, and he wanted to speak to the actor. Tennessee had no relationship with the actor, but he had admiration, and he had curiosity. Tennessee called on his friends John Gielgud and Irene Worth to arrange a meeting, and Tennessee found himself both in person and in telephone conversations with Alec Guinness. Tennessee spoke to me of the kindness of Alec Guinness in 1982. In 1991, by telephone, Alec Guinness spoke to me of Tennessee Williams and his desire to be good.

James Grissom: “Why do you think Tennessee reached out to you?”

Alec Guinness: “I don’t know. I don’t really care, either. I feel—and I felt—that when someone reaches out to you, you reply, even if to say you don’t know what to do or why. Why did I respond to you? It is courtesy. There is also curiosity. I want to know what Tennessee Williams was feeling and thinking, and I want to know what he was saying to a young man in the final months of his life. Marian [Seldes] spoke to me of his calling her and describing what he was finally able to say to you. I remember thinking, Finally? Was there no one to whom he could speak? I think he was being melodramatic. That sounds harsh, and I don’t mean it, but we often get in an unhappy condition and say, I have never been happy in my life! Or, no one cares about me. I know that Tennessee had friends who listened to him, but I think the circumstance of being with someone so young, so curious, so eager, afforded him a new way of talking, of sharing.

“But back to the question: I didn’t think I could be of any help to Tennessee on a theological level, but he knew where to go for that. Tennessee wanted to speak to another person who had found himself in need of a particular church at a particular time, and he wanted to ask for directions as to how to get around. As it happened, Tennessee and I were seeking the church for similar reasons.”

James Grissom: “What were they?”

Alec Guinness: “My son had become very, very ill. My wife and I were preparing for the worst. We were preparing for his death. We were both very deep in the dark. I suddenly felt unmoored. I had known sadness and loss and depression before, but I had always had something, someone, to whom I could attach myself for support, or as a sort of bearing. I could devote myself to a book or a play. I could lose my depression in the study of something else. Nothing gave me strength or comfort with my son’s illness. I am not a doctor. I am not a theologian. I was just an actor, waiting always for the next opportunity to escape into a character or a situation.

“I had some scant experience with religion, and I began to pray. I found it comforting. I found it comforting to believe that a power might be there for me, might give me strength to endure whatever was coming. I will admit that I held out for the hope of a miracle: That God would hear my prayers and heal my son. Give my son more time. Give me more time with my son. But the foundation of my prayers was always for strength, for courage in facing what was coming, good or bad. I felt that I had been operating for so long without a foundation. Tennessee said he felt the floor had collapsed beneath him. The dreaming and the writing were no longer working. Where had he lost it? I spoke of my foundation to operate. Tennessee liked to refer to his faith as scaffolding. That was a term he used with me. I like that. Scaffolding will also work. If faith is scaffolding, it is holding this building—our bodies—together, and within this building is faith—a faith—that might get us and those we love through whatever we’re facing. That is what Tennessee was dealing with. I had dealt with that. I just saw it—this opportunity to talk—as something I could and should do for another person, another pilgrim, who was lost. I did what I could. And those conversations, whether or not they were ultimately helpful to Tennessee, were valuable to me in reminding me of what my faith meant to me. What my faith had done for me.”

James Grissom: “Tennessee said you showed up for him. A great Christian act.”

Alec Guinness: “We show up for others. That would seem to be to be the minimum we can do. To be present. To do what we can. The simplest apostolic act.”